‘The Passing of Eleanor’ – artist’s impression of the funeral cortège of Eleanor of Castile watched over by her grieving husband, Edward I. Artist Frank Salisbury, 1910 (1).

‘The Passing of Eleanor’ – artist’s impression of the funeral cortège of Eleanor of Castile watched over by her grieving husband, Edward I. Artist Frank Salisbury, 1910 (1).

‘Pray for our consort, who in life, we loved dearly, and, dead, we do not cease to love….’

Edward Ist in a letter to the Abbot of Cluny, France, 4 January 1291….

Queen Eleanor (birth name Leonor de Castilla) died on Tuesday 28 November 1290 ending a marriage that had lasted for thirty-six years. They had married in November 1254, when Edward (1239-1307) was 15 and Eleanor (1241-1290) 13. Their political story can be found elsewhere, and, not wanting to destroy the ethos of this part of their story, I won’t go into it here only suffice to say that personally, and fortunately, for them, an enduring love grew between them, and they would go on to produce a massive brood of 16 children although the majority of them would sadly predecease their parents.

While travelling northwards Eleanor became too ill to continue the journey and was taken to the manor house of Richard de Weston at Harby in the parish of North Clifton on the Trent, Nottinghamshire. I would love to know more about this man who was, presumably, minding his own business when the royal cavalcade descended upon him complete with a dying queen. However I appear to be going off on one of my tangents and so back to the royal couple. I have been unable to ascertain whether Edward and Eleanor were travelling together when she became too ill to continue and they diverted to Harby or whether the king was further north and travelled back south to Harby when news reached him of his ailing queen. The consensus is though that he was present at her bedside as she breathed her last, as well as the local priest, William de Kelm and the Bishop of Lincoln, Oliver Sutton (2). Eleanor appears to have been ailing for some time with payments in her privy purse accounts for various syrups as well as a special silver vessel which was probably to store them in. Eleanor was struck down by a low fever which was probably the quartan fever (a form of malaria) she had contracted in 1287 although it has also been suggested she may have suffered from consumption. Edward perhaps laid low with grief remained at Harby for several days although of course it would have taken some time to arrange a suitable hearse and the other minutiae necessary for what would have been an extremely gruelling journey for the king. Was it during these first sad days the plan begun to form in Edward’s mind to erect crosses to commemorate every place that his late wife’s body rested overnight on her last journey to the final destination of Westminster Abbey? I will return to Harby below. Whenever it was is unrecorded but other than that there is an absolute wealth of information out there covering the ‘Eleanor Crosses’. Ah thought I, writing this post is going to be a doddle! There are even plain and simple maps – for those of us who are not proficient map readers – which showing the 12 stopping points in a nice straight line on the A1 which was then called the Great North Road. This prima facie makes perfect sense for surely the sad cortege would have wanted to get from A to B by the easiest route not via the scenic one. How puzzling though – warning bells begun sounding in my bonce – that if the journey took twenty-one nights and a cross was built at every place where the coffin rested overnight there are only twelve of them? (3). Anyway onwards… These stopping points were, we are reliably informed, as follows: Lincoln, Grantham, Stamford, Geddington, Hardingstone nr Northampton, Stony Stratford, Woburn, Dunstable, St Albans, Waltham, Westcheap (now Cheapside) and Charing (now Charing Cross). Three of these places still have their crosses up until today. This is one post that shouldn’t prove too onerous and what’s not to like – I shall be finished by tea time! However I had hardly begun when I happened upon an intriguing comment by Charles A Stothard (5 July 1786 – 28 May 1821) which threw a spanner in the works. Now Stothard was a remarkably gifted English antiquarian draughtsman who knew everything but everything there was to know about ancient monuments. He made it his lifetimes work to meticulously record and describe medieval monuments as they were in his time and while many of them still retained some of their original colouring and gilding. His artworks are all contained in a beautiful book – The Monumental Effigies of Great Britain – which I cannot recommend highly enough.

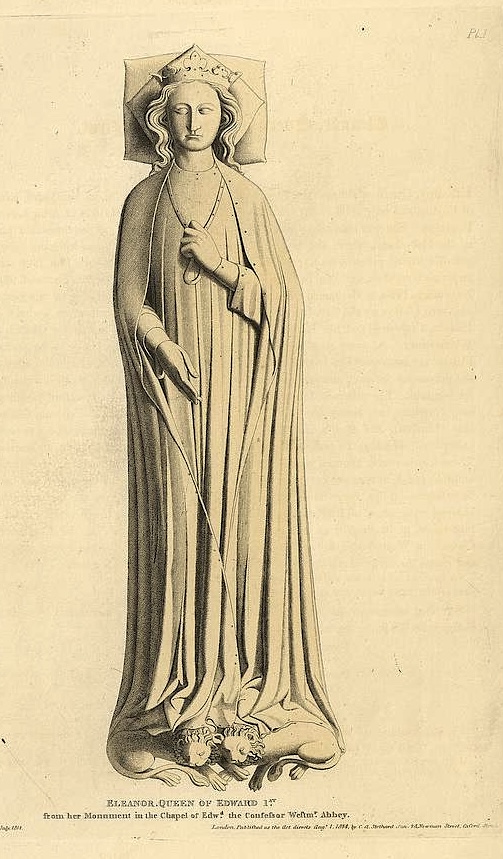

Charles Stothard’s drawing of the effigy of Eleanor, Queen of Edward Ist. Edward the Confessor’s Chapel, Westminster Abbey.

But to get back to the Eleanor Crosses. In his book Stothard made the statement, which oddly has been overlooked in most accounts written about the Crosses, that despite historians only noting twelve crosses there were actually fifteen – three of them having been omitted by ‘some authorities’. By gad! Could this be correct? Having unequivocal faith in Stothard I was delighted to come across Bob Speel’s excellent blog wherein he reinforces Stothard’s statement pointing out that : ‘There seem to have been up to 15 such (overnight) stops, and the precise route of the procession and the number of crosses is not certain. (Yikes!) They have been supposed to be at Hardeby, Lincoln, Newark, Leicester, Geddington, Northampton (Hardingstone), Stony Stratford, Dunstable, St Albans, Waltham, Cheapside, and Charing by Westminster. An alternative account supposes Stamford and Grantham itself rather than Newark and Leicester, and Woburn has also been suggested’. So if all of these above mentioned places were indeed actual overnight stopping points then you would have your fifteen crosses ..bingo! There is also some confusion as to whether one or two nights were spent at some destinations – for example Stamford, Hardingstone (on the outskirts of Northampton) and Geddington (4). So let’s begin by taking a look at the three places that Stothard stated (and also mentioned by Bob Speers) had Eleanor Crosses but are omitted from the regular and accepted list:

HARBY/HARDEBY – As mentioned above, while journeying northwards Eleanor’s condition deteriorated so much she had been taken to the manor house of Richard de Weston at Harby. It does seem a little strange Edward would have omitted Harby, the very place where his wife died, from the list of places to be given a cross although in all fairness it has to be mentioned that he did have a chapel built there. Did he think that would suffice or did he, as Stothard says, install a cross there too? Interestingly in the heart of this small village is a road by the name of Cross Lane. This could merely indicate it was the area where four roads merged or could it be in recognition of a cross that once stood there – cross roads being, in the main, the very place an Eleanor Cross would be erected. The absence of the remains of a cross should not imply that there never was one. Many of the other crosses have left nothing behind – not a single pebble – as evidence they were ever there. If we remember that the Eleanor Crosses were standing crosses i.e. completely free standing then it can be seen that given the will, when demolished, these crosses could easily disappear without a trace and eventually from memory.

The area where Richard de Weston’s manor house stood at Harby, Nottinghamshire. View from behind the church. Picture Minster Lovell with its close proximity to the church to give an idea of the appearance of the manor house..

NEWARK, NOTTINGHAMSHIRE – Newark is on what was known then as the Great North Road – now the AI – and lying being betwixt Lincoln and Grantham would have made a perfect overnight stop. Newark being 18 miles from Lincoln and approximately 14 miles from Grantham would surely have been an easier route for a large cumbersome funeral procession than a 25 mile journey from Lincoln to Grantham on what may possibly have been not such a good road. Also Newark had a castle – a convenient place for the king to stay. To strengthen this theory is the fact that there is indeed an ancient cross at Newark known as the Beaumond Cross although the true identity of the cross has become muddled over the centuries. This cross has now been removed from its original site at a once important road junction in 1965 and now stands in Beaumond Gardens. Historic England – in a not too well researched article – does say that it has been suggested that it is an Eleanor cross but then strongly veers towards the tradition and ‘recorded evidence‘ that it was erected by the widow of John Beaumont, First Viscount Beaumont, following his death at the Battle of Towton in 1461. To be honest this is nonsense – as well as baffling – as a minimum amount of research leads you to early 20th century Nottinghamshire historian Thomas Blagg F.S.A. who recorded that the area ‘has been known as Le Beaumond from time immemorial being so named in a deed as early as 1310 and the first documentary mention of the cross itself – ‘Beaumond Crosse’ – hitherto discovered in a deed of 1367′ (5). Furthermore Viscount Beaumont actually fell at the Battle of Northampton in 1460 not Towton, which was where his son fought, so excuse me if I do not find said ‘recorded evidence‘ (which is what by the way?) confidence inspiring. I have also been unable, so far, to find any connection with Viscount Beaumont to Newark with his estates being in the main situated in Lincolnshire and Leicestershire. Further strong arguments for the cross being an Eleanor Cross or incorporating parts of an Eleanor Cross have been made by another late 19th century Nottinghamshire historian, William Stevenson. who makes no bones about dating the cross to the 13th or early 14th century. Describing the monument as ‘Having survived the town sieges during the Civil war, to becoming an object of profound interest in the 20th century, with photography as an aid brought to bear upon its probable or close date of erection’. Stevenson goes on to describe the cross as : ‘ A good and even an elaborate example of Edwardian English Gothic architecture, or when that art was at its best; this broad term dates from the first year of Edward I (1272)—to the last of Edward III(1377). However the cross we have today may not be the original one in its entirety as the Cross was repaired in 1778 when a plaque was added stating ‘This cross, erected in the reign of Edward the Fourth (1461-1483), was repaired and beautified from the town estates A.D., MDCCCI.’ However he further explains that ‘this Edward IV date was singled out from time on the assumed evidence of a Lord Beaumont who was wrongly supposed to have been a local celebrity, and wrongly stated to have been killed at the battle of Towton Field, 1461. This error crept in from a desire to date the cross, with nothing but its popular name to work upon, which may only have been a descriptive one—’the fair-mount’ – of the ground thereabout. We first hear of the local name Beaumond in a deed dated 1310, and incidentally of the cross, itself in 1367′ Additionally he notes that the Bishop of Lincoln who officiated at Eleanor’s funeral owned either Newark castle or a substantial property in the area which would have offered suitable accommodation for the king (6). However perhaps Historic England have not come across the Blagg or Stevenson articles nor indeed happened upon Charles Stothard. And thus, dear reader are legends born – which is both tragic and annoying in equal measures. Historic England further describes the Beaumond Cross as having the socle (i.e. plinth) and shaft of a medieval cross (there’s a clue!) with the shaft containing a robed figure who they think may be a saint or Christ but that may be just sheer guesswork on their part as the figure is extremely worn.

Artist’s impression of Beaumond Cross, Newark, Nottinghamshire. Artist Joseph Paul (1804-1807). Newark Town Hall and Art Gallery.

LEICESTER – This prima facie seems a bit more difficult to explain. But is it? Approximately 39 miles to the west of Stamford which is deemed by many to be the next stop after Grantham, it begs the question if Stothard was correct in that Leicester did have an Eleanor cross, why would the cortège swing out so far westwards instead of continuing on the more direct route via today’s A1 then known as The Great North Road. Well it transpires there were strong reasons for not taking that most straightforward route. Bearing in mind we are talking about winter months here it is known that ‘Great North Road south of Stamford, particularly where it crossed the Nene and Ouse valleys, was often impassible in wet weather, while the western diversion, though longer, kept to higher ground’ (7).

This begs the question was the funeral cortege after its arrival at Stamford unable to continue its journey southwards due to flooding? Or was it always King Edward’s intention to travel westwards to Leicester for some reason now lost to us. Certainly Leicester with its castle and fine abbey would have provided suitable stopping point for the royal party. If so the route taken could have been via the A47 even then an ancient road having been in use since Roman times. The Great North Road could have been rejoined later also via the A47 and thence on to Geddington.

We will return to Stamford below but first to return to Leicester. It is known that there was indeed a stone cross in the 13th century where the High Street met with Highcross Street. This junction became known as High Cross. A cross today stands in Jubilee Square which is topped by a column which is said to be from the High Cross that was built in 1577. This cross which has been moved several times in its lifetime may have replaced the 13th century cross and could the more ancient cross have been an Eleanor Cross as Stothard said?

This covers the three extra places said by Stothard to have had Eleanor crosses. If only he had left us his sources! However now to return to the accepted journey…

LINCOLN

The funeral cortège left Harby and travelled the seven miles to Lincoln. There on Sunday 3 December the sad procession reached St Catherine’s Priory, Lincoln where Eleanor’s body was eviscerated and embalmed. Her viscera was interred in the Chapel of St Mary in Lincoln Cathedral and her body and heart recommenced the journey to London.

The cross to mark her first resting place was erected in 1292. It stood outside the city walls to the south at an important road junction by St Catherine’s Priory until it was destroyed some time during the English Civil War (8).

Drawing of the tomb of Eleanor of Castile d.1290 in the Lady Chapel, Lincoln Cathedral c.1631. Artist William Sedgwick. Credit with thanks to the British Library. Destroyed soon after this drawing was made in the English Civil War.

All that remains of the Lincoln Eleanor Cross today are the lower folds of Eleanor’s gown(9).

STAMFORD, LINCOLNSHIRE

The cross is recorded by two 17th century eyewitness accounts as having stood about half a mile outside of the town on a hill on the left hand side of the Great Chasterton road that run north of Samford. As to why the cross stood outside of Stamford may be the visual impact of the cross standing on top of a hill. Imagine it!

‘In the hill before ye into the towne stands a lofty large cross built by Edward I in the memory of Eleanor whose corps rested there coming from the north. Upon the top of this cross these three shields are often carved: England: three bends sinister: a bordure (Ponthieu): Quarterly Castile and Leon’ (10).

‘Near unto the York highway, and about twelve score paces from the town gate, which is called Clement Gate, stands an ancient crosse of freestone, of very considerable fabric, having many ancient scutcheons or arms insculpted in the stone about it as the arms of Castille and Leon quartered, being the paternal coat of the King of Spain, and divers other hatchments belonging to that crown, which envious time hath so defaced that only the ruins appear to my eye, and therefore not to be described by my pen’ (11).

Some remains of the cross – Purbeck marble with a rose carved on one of its surfaces – have been discovered in the garden of Stukeley House. In the 18th this house belonged to William Stukeley, a noted antiquary who claimed to have found the remains of the cross in December 1745 on Anemone Hill on the Upper Chasterton Road. The cross is believed to have been destroyed between 1646 and 1660 by Parliamentary forces (12).

GEDDINGTON (Northamptonshire)

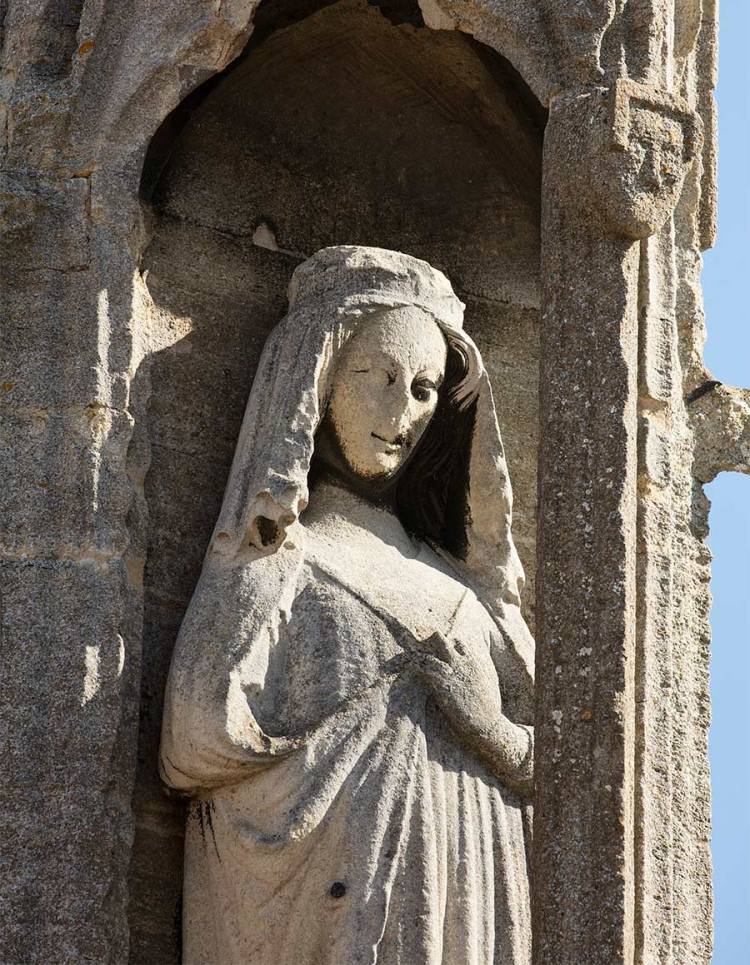

The cortège arrived in Geddington on the 6 December. No doubt bitter sweet memories overcome Edward for the royal couple, said to have both enjoyed hunting, had spent happy times in the hunting lodge there and had last stayed there as recently as September of that year. Eleanor’s coffin would have rested in the parish church, St Mary Magdalene, while Edward spent the night at the hunting lodge. The Geddington cross is the finest of the three surviving crosses. Poignantly the shaft of the cross rests on a base that resembles a tombstone giving the impression that the cross is growing out of Eleanor’s tomb. The shaft itself is decorated with an abundance of roses perhaps in a nod to Eleanor’s love of gardens. Further up the shaft are three beautiful, although damaged, statues of Eleanor portrayed as a young queen.

Base of the cross. Note the roses on the shaft. Photos thanks to English Heritage.

Photos thanks to English Heritage.

HARDINGSTONE, NORTHAMPTONSHIRE

The position of the cross, one of the three survivors, outside the town suggests that Eleanor’s coffin rested overnight at nearby Delapré Abbey. Several carvings of books – the pages of which may have had prayers engraved upon them – adorn the cross which may be a nod to Eleanor being an avid collector of books. The mason was John of Battle and cost just over £100.

Carvings of books and heraldic shields still on the cross today. Photo thanks to english-heritage.org.uk

Delapré Abbey shown in a Ordnance Survey map of 1897. The Eleanor Cross is shown on the road to the south of the Abbey. Map with thanks to an interesting blog A London Inheritance.

The worn but still lovely statues of Eleanor have miraculously survived the centuries. Another nice photo from A London Inheritance.

STONY STRATFORD, BUCKINGHAMSHIRE

The cortege reached Stony Stratford on Saturday the 9th December. John of Battle and his team also built the cross here but this time in the High Street itself. Today a plaque commemorating the cross can be found marking the spot. Presumed to have been destroyed in the english Civil War.

WOBURN ABBEY, BEDFORDSHIRE

It is thought that Edward may have left the party at this point to travel to St Albans where a new bishop was being elected. This cross was also built by the industrious John of Battle and his team. The precise site of the cross is now lost but it’s known that the funeral party stayed at the Cistercian Abbey of Woburn overnight. Woburn Abbey would later become a victim of the Dissolution of the Abbeys.

DUNSTABLE, BEDFORDSHIRE

On Monday II December the cortège travelled a short distance of just 9 miles to Dunstable Priory still without the king. It is recorded in the Priory’s archives that

‘When the body of Queen Eleanor passed through Dunstable, it was placed in the middle of the marketplace, with a reliquary on top, until the Lord Chancellor and the nobles who had gone there chose an appropriate place where they would later erect a cross of admirable size. … and our prior sprinkled holy water to bless the chosen place (13).

Depending on what account you read some confusion exists over whether only the bier stood in the market place while the coffin was placed before the altar of the Priory church or whether the coffin was left at the market place for a short while before being taken to the church overnight or did the coffin plus bier spend the whole stay in the market place. However I find it really difficult to believe that the Queen’s coffin was left in the market place for even a short period of time so we can swiftly discount that option (14). Needless to say it was once again John of Battle, in 1291, who built the cross which was described by William Camden a 16th century antiquarian as being decorated with the heraldic arms and statues of Eleanor. Destroyed by Parliamentary forces in 1643 the site is marked now by a plaque.

ST ALBANS

It was here that on the 12 December Edward and the cortege reunited. They continued to the Abbey where the chronicler recorded:

‘When her body … approached St Albans all the abbey, solemnly dressed in albs and copes, went out to meet it at the church of St Michael on the edge of the town. From there her body was taken to the choir of the church, before the high altar. That whole night it was honoured by the entire abbey with great devotion, with services and holy vigils.

The cross which was built facing the abbey was once again the work of John of Battle – his fifth – at a cost of about £100. As intended the cross became a focal point with various events taking place including the rebellious folk who in 1381 burnt muniments taken from the Abbey and later read out their short lived charter of freedom. It was here also that the “heretical” books of the Lollard Walter Redhed of Barnet were burnt after he recanted in 1426/7. It is reported that, in 1643, the High Sheriff of Hertfordshire read a Royal Proclamation from the steps of the Eleanor Cross, advocating the raising of Trained Bands. He was arrested by one Captain Oliver Cromwell for his pains (15).

The cross – of which no images have survived – was in a perilous state by the 17th century until no more than a stump remained which was ordered to be removed in by the town authorities in 1701.

WALTHAM CROSS

Waltham Cross, Hertfordshire. Engraving by George Vertue after a drawing William Stukeley. Published by the Society of Antiquarians of London 1721.

As the crosses neared London so they grew more grander and the cross at Waltham echoed this being constructed in 1291-92 by master masons Roger of Crundale and Nicholas Dymenge while Alexander of Abingdon created the statues of Eleanor at a cost of just over £110.

Nearing the end of their sorrowful journey and reaching London the crosses become even more splendid and the costs rose steeply from what seems to be on average £100 to £300 for the one raised at Cheapside.

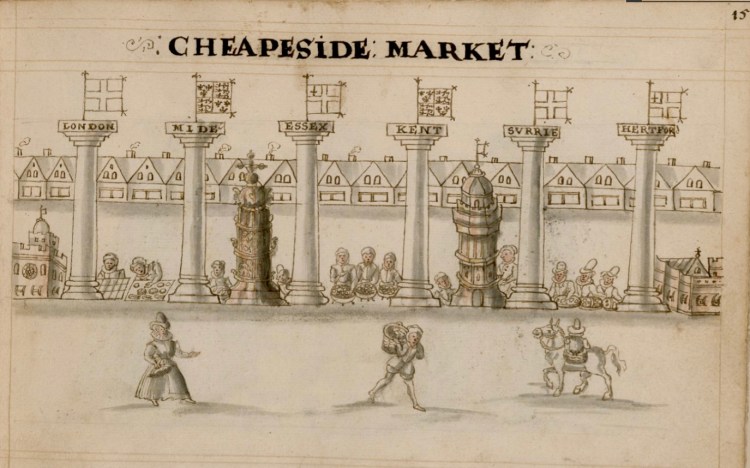

CHEAPSIDE, LONDON The cross built in 1290 – which stood on Cheapside street between Friday Street and Wood Street – became a focus point for celebrations and civic pageantry. Races were begun from there as well as jousts held there in the reign of Edward III. Perhaps its most notable event was upon Henry V’s victorious return from Agincourt 1415 when he was greeted at Cheapside Cross by a choir of maidens dressed in virginal white (16).

Stow tells us that in 1441 the Lord Mayor, John Hatherley, gained permission from Henry VI to rebuild the cross which ‘being by length of time decaied – to reedifie the same in more bewtifull maner, for the honor of the citie‘. The new cross was completed in 1486 after being ‘newe gilt all ouer‘

‘A caveatt for the citty of London, or, a forewarninge of offences against penall lawes’. Artist Hugh Alley 1556-1602. Cheapside Market c.1598. The Eleanor cross, regilded all over, can be seen to the left.

Described by Stow in 1598 as being ‘of old time a fayre peece of work‘ but by the beginning of the 17th century Sugden recorded the cross ‘had fallen into a very ruinous condition‘. Far from being saved again the writing was on the wall and the end came when it was demolished by Parliamentary solders on the 2 May 1643 accompanied by drums beating, trumpets blowing and ‘multitudes of cappes‘ thrown in the air.

CHARING – A hamlet in the 14 century. The original cross – which was the most expensive costing £600 – was built by Richard and Robert Crundale between 129I-3. Now replaced by an equestrian statue of Charles Ist, the cross stood just to the west of the modern copy of it that stands outside Charing Cross Station.

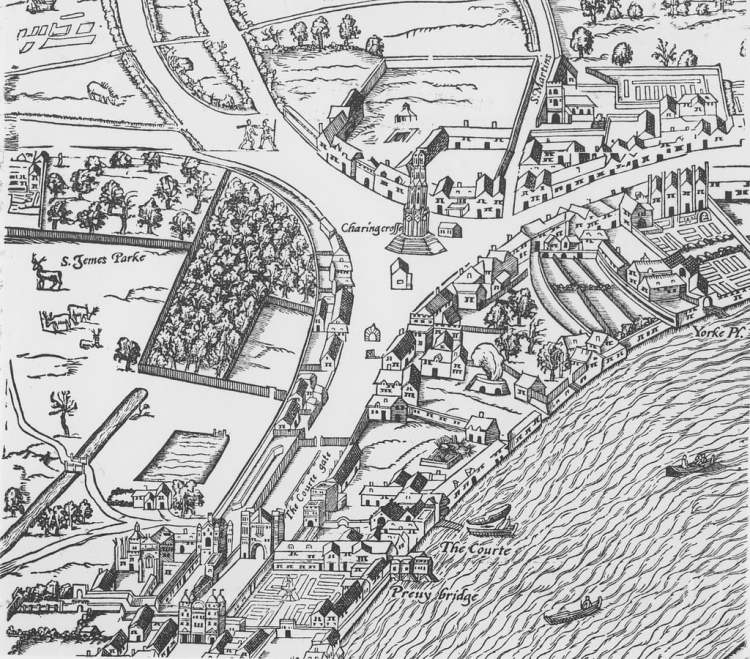

Detail of Charing Cross from Civitas Londinium. 1561. Artist Ralph Agas London Metropolitan Archives (City of London)

Detail of Charing Cross from Civitas Londinium. 1561. Artist Ralph Agas London Metropolitan Archives (City of London)

There would also be a second smaller tomb in London which was erected in the church of the Dominican Black Friars, where Eleanor’s heart was buried, and where the heart of her son, 10-year-old prince Alfonso, who had died on the 19th of August 1284, had been previously interred (17).