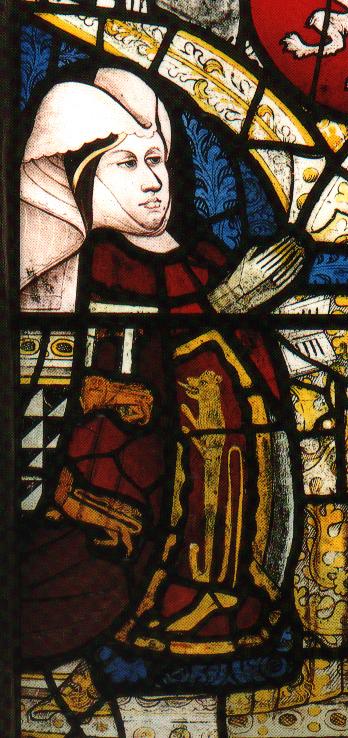

Unfortunately no reliable image has survived of Eleanor Butler/Boteler née Talbot but the above image of her younger sister, Elizabeth, duchess of Norfolk, may give us some idea of her appearance. 15th century stained glass. Holy Trinity Church, Long Melford, Suffolk.

Dear Reader – since I begun the writing of this post, and doing some delving, as you do, I have to say I have changed my mind somewhat as to exactly how ‘secret’ the marriage of Lady Eleanor Talbot (d.1468) and Edward IV (b.1442-d.1483) actually was – but more about that later. This marriage, which I will refer to here as the Talbot marriage, made possibly in February 1461, has been called a ‘precontract’ which has confused some people into thinking it was merely some sort of engagement and not what it actually was – a legal and binding marriage. That an earlier legally binding marriage had indeed taken place – thus putting the legitimacy of the children of Edward and Queen Elizabeth Wydeville (c.1437-1492) in jeopardy – had certainly been mooted as early as 1478 because it was somewhere around then that Elizabeth had become aware she was in the awkward position of being the bigamous wife of Edward IV. We know this because Mancini reported that by then she knew that by established custom (ie a long held belief) she was not the legal wife of the king (1). Worse, much worse still, was the fact that among those who were aware her marriage was bigamous was none other than her brother-in-law George, duke of Clarence, who had links with Bishop Stillington who in turn had links to the Talbot marriage. What to do? Clearly the awful realisation would also have dawned on her that her marriage to Edward, being invalid, rendered their children illegitimate and according to the canon laws of the times unable to inherit. This applied especially to Edward’s heir Edward, Prince of Wales, who would be unable to inherit the throne upon the death of his father. Presuming that Elizabeth had been unaware at the time of her ‘marriage’ to Edward the eventual dawning of the truth led a probably highly panicked Elizabeth to ‘persuade’ her husband, apparently without too much difficulty, to execute his brother to silence him. Oh to have been a fly on the wall to witness those hairy scenes between Edward and Elizabeth! Mancini’s report describing how the queen, and others, knew about the first legal marriage derails the argument that it was nothing more than a falsehood and ruse invented in 1483 to enable Gloucester to take the throne. Thus another myth bites the dust. If it was indeed the case, as seems highly likely, that the Talbot marriage was fairly common knowledge then it makes it difficult to understand how Richard duke of Gloucester was actually in the dark about it as late as 1483. Did he indeed know about the story, but his well known loyalty to Edward led him to remain silent until his brother’s death and the emergence of the truth into the open forced his hand? The existence of Edward’s first legal marriage is supported by several primary sources i.e. Croyland Chronicler, Mancini, de Commynes and as mentioned even Edward’s queen, Elizabeth Wydeville.

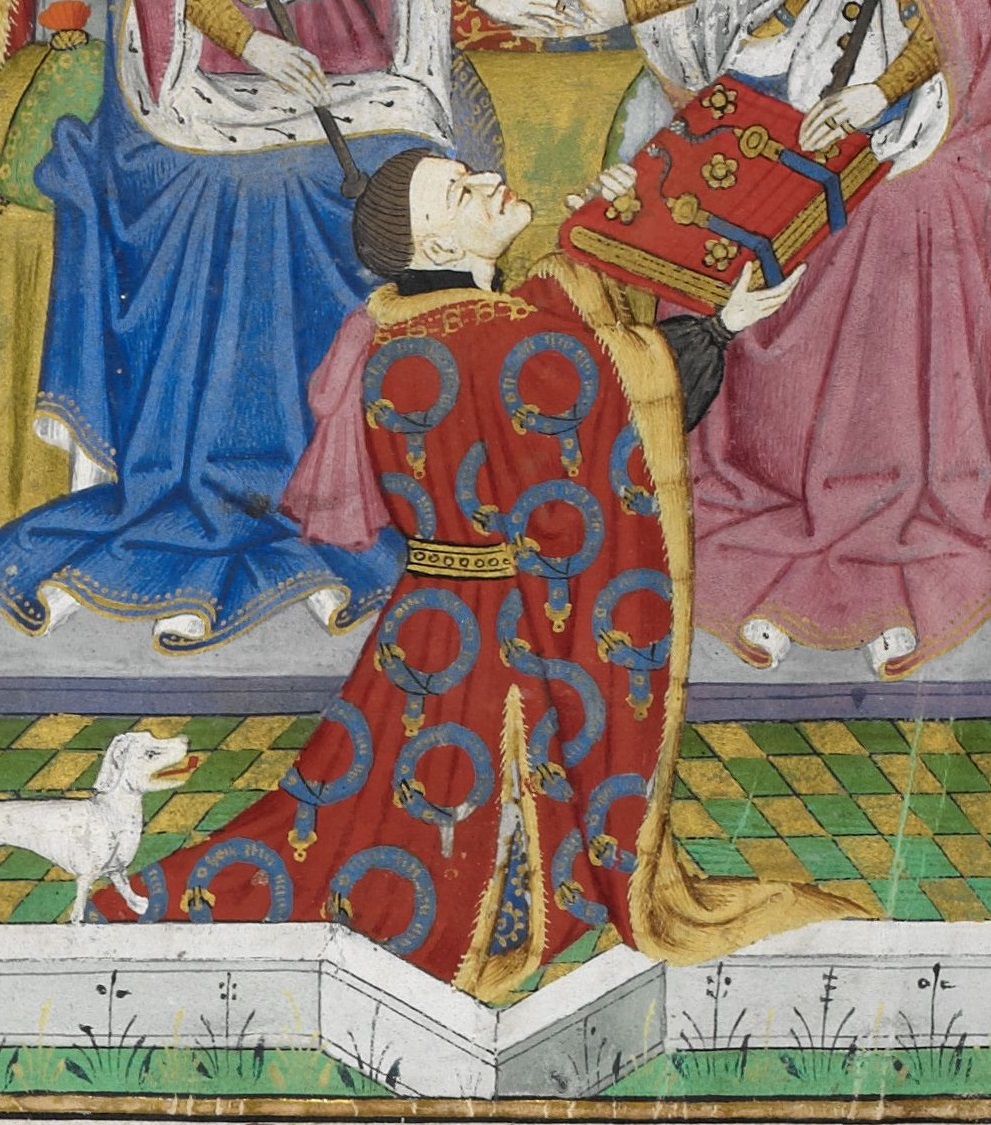

Elizabeth Wydeville. Mancini reported that alarmed that she was not the true wife of Edward IV she persuaded him to execute his brother, George duke of Clarence. Royal Collection, Windsor.

Lady Eleanor Butler/Boteler née Talbot (d.1468)

Eleanor was named in the Titulus Regius as the woman who was the first and legal wife of Edward IV, making his later clandestine ‘marriage’ to Elizabeth Wydeville in May 1464 bigamous and the children from that marriage illegitimate and thus unable to take the throne. It was de Commynes who stated that Edward and Eleanor’s marriage was witnessed by Robert Stillington who was not, at that point, the Bishop of Bath and Wells, but certainly a royal counsellor. Quidquid at whatever point Stillington discovered the truth is not crucial to our story. But find out he did for around the time of Clarence’s execution in 1478 the Bishop found himself swiftly incarcerated in the Tower of London as well as heavily fined. I’ll return to this point later.

Eleanor seemed for a long time just a mere footnote in 15th century history although she was at the epicentre of one of the most disruptive episodes from those times and indeed, it could be said, the catalyst for the fall of the House of York. Who was she exactly, this widowed lady some of the chroniclers from the period and even modern historians have tried to brush under the carpet? Thanks to the late historian John Ashdown-Hill we actually now know quite a bit about her.

CHILDHOOD

Eleanor came from an extremely high status family being the daughter of John Talbot, first earl of Shrewsbury (1387-1453) known as ‘Old Talbot’, and his second wife, the formidable Margaret Beauchamp (1404 – 1467).

John Talbot lived a substantial part of his life as a soldier, including a very long stint in France – four years of which were spent as a prisoner. His military career is well documented elsewhere and I won’t go into it here. He seems to have acquired a reputation for sometimes overstepping the mark and it was noted by a Welsh commentator that ‘from the time of Herod there came not anyone more wicked‘ (2). However a propensity for violence was not deemed a handicap in those times. He must have seen his family, including of course the young Eleanor, only rarely, and it’s interesting to wonder what she made of him on those few occasions she did meet him. Was she scared stiff of him or did he soften around his offspring? Whatever it was his luck run out at the battle of Castillion on the 17 July 1453. Perhaps it was not so much his luck running out because there is a story that he chose to ride into battle minus his armour which he had sworn never to don again in the field against the forces of the French king, Charles (3). Whether this actually happened I know not. To the modern mind it’s a completely crackpot idea but for the medieval mindset no doubt it would have been viewed as not only rational but actually noble too! What is certain however is that his son, Eleanor’s brother, John Talbot, Ist viscount Lisle (born c.1426) also perished that day. Talbot was viewed as an English hero and the French respected him enough him to raise a monument to him after his death:

“Such was the end of this famous and renowned English leader who for so long had been one of the most formidable thorns in the side of the French, who regarded him with terror and dismay” – Matthew d’Escourcy

He remained buried in France for forty years until his body was brought back to England by his grandson, Sir Gilbert, and interred, according to the terms of his will, in St Alkmund’s Church, Whitchurch, Shropshire (4). Such was Eleanor’s father.

John Talbot, Ist earl of Shrewsbury. Note the talbot hound. Detail from the Talbot Shrewsbury book. Shown presenting the book to Margaret of Anjou.

Her mother Margaret Beauchamp was the eldest daughter of Richard Beauchamp, earl of Warwick (1382-1439) and her mother was Beauchamp’s first wife Elizabeth Berkeley. This Richard Beauchamp was also the father of Anne Beauchamp countess of Warwick suo jure (1426-1492) whose mother was Beauchamp’s second wife, Isobel Dispenser – please keep up at the back Dear Reader….. Anne Beauchamp married Richard Neville, earl of Warwick (1428-1471) later known as the ‘Kingmaker’. Thus Eleanor was cousin to Queen Anne Neville, Richard III’s wife and Isobel Neville, duchess of Clarence, wife to George, duke of Clarence who was executed in 1478, an execution described by some historians, including Michael Hicks, as a judicial murder. We will return to George later (5).

Effigy of Richard Beauchamp in the Beauchamp Chapel of St Mary’s Church, Warwick. Lady Eleanor Talbot’s illustrious grandfather. This wonderful effigy is the work of William Austen. Photo Aiden McRae Thomson @ Flkr.

FURTHER ILLUSTRIOUS FAMILIAL LINKS

Eleanor also had three brothers and two sisters. In one of history’s many strange quirks her elder brother John had a daughter, Elizabeth Talbot, (1451-1487) who became viscountess Lisle, after marrying Edward Grey, viscount Lisle. This Edward Grey’s brother was none other than Elizabeth Wydville’s first husband, Sir John Grey, who had married her in 1452. Elizabeth Talbot would have still been a child when Sir John died possibly fighting for Lancaster at St Albans 1461 and it’s unlikely she met him. However Elizabeth Talbot’s aunt, Elizabeth Talbot, Mowbray duchess of Norfolk, would surely have recalled the time when Queen Elizabeth Wydeville had been merely Lady Grey, and thus related by marriage to the Talbot family, but she unfortunately left no indications of her thoughts on the bigamous Wydeville marriage and its disastrous results although she must have had them aplenty.

Elizabeth Talbot. Eleanor’s niece. c1468. Artist Petrus Christus of Bruge Gemäldegalerie, Berlin. May have been painted in Burgundy at the time of Margaret of York’s marriage to Charles the Bold 1468. Elizabeth, Duchess of Norfolk would have been in Burgundy at that time and was accompanied by members of her family.

Eleanor’s above mentioned younger sister, Elizabeth, duchess of Norfolk, became the wife of John Mowbray, duke of Norfolk who died suddenly and unexpectedly during the night of 16–17 January 1476 (6). Elizabeth’s three year old daughter Anne, now the wealthy Norfolk heiress, was married to the even younger Richard of Shrewsbury, duke of York. You can read about Elizabeth and Anne’s tragic stories here and here.

These distinguished familial links stretched far and wide and appear to have gone somewhat unnoticed. However illustrious her family line was, Eleanor seems prima facie to have been treated with scant respect by the young Edward IV although to be fair the circumstances of how they parted are very much lost in time. Sir George Buc/Buck who had access to many ancient documents recorded in his History of Richard III that Edward ‘for a time loved the lady but later ‘too soon growing out of liking her he entertained others into the bosom of his pleasure’. It was Buc who named Bishop Stillington as the priest who had conducted, or at least witnessed, the marriage with ‘no persons being present, but they twain and he’ and also that ‘the king charged him very strictly that he should not reveal this secret to any man living’. Buc also asserted that a child had been born from their union. Perhaps Eleanor had a lucky escape for Edward would go on to earn a reputation of ‘ a gross man…. addicted to conviviality, vanity, drunkenness, extravagance, and passion‘. And that is not all, for Edward also gained a further reputation for using ladies and abandoning them, even going so far as to hand them on to his courtiers whether they liked it or not: ‘In carnal lust he indulged to an extreme, while his behaviour was also said to have been most insulting to many women after he had possessed them, for as soon as his lust was sated he passed them on, much against their will, to other members of his court. Married or single, high-born or lowly, it made no difference. However, he ravished none by force, all were prevailed upon by means of money or promises and having prevailed he dropped them’ (7).

One less exalted, but intriguing, further link by marriage was that to William Catesby. a successful lawyer who was William, lord Hastings, protégé. Eleanor’s father had a younger sister, Alice. Alice married Sir Thomas Barre of Burford. They had a daughter Joan/Jane who married Sir Kynard de la Bere. After she was widowed, Joan would marry the widowed Sir William Catesby Snr, thus becoming our Catesby’s stepmother. After Hastings execution William grew even more successful and even more wealthy. It is tempting to speculate exactly how much he knew about the Talbot marriage. The wily Henry VII had him executed two days after Bosworth.

Yet another interesting link is Eleanor’s step-mother-in-law – Alice Lovell née Deincourt. Alice was the grandmother of Francis viscount Lovell – who is renowned for being a close and loyal friend to Richard III.

The importance of these familial links should not be downplayed. When Eleanor was named as the legal wife of Edward IV in the Titulus Regius it was as historian John Ashdown-Hill pointed out, that her ‘rank and plausibility as a possible royal consort were immediately established’ and as well as being the daughter of an earl she was ‘equal in rank to Edward’s own mother, Cicely Neville (8). It should be noted that none of her family stepped forward to complain about her being named as the wife of Edward IV which leads to the conclusion that she was indeed the lady Edward had married prior to his bigamous marriage to Elizabeth Wydeville.

FIRST MARRIAGE

Eleanor’s date of birth is unknown but her first marriage took place in 1450 when she married Sir Thomas Boteler whose father was Ralph Boteler, first baron Sudeley (c.1391-1473) when she was probably aged about 13-15 and Thomas 28. Eleanor brought with her a generous dowry of £1000. In return the Boteler family would have provided her jointure i.e. ‘the property which her father-in-law would provide her and her husband to live on and which Eleanor would retain for the rest of her life should she outlive her husband’ (9). There is some confusion as to the date of Thomas’ death or the cause of it and we can only safely say he died some time prior to 1460.

Following her marriage to Edward which according to John Ashdown Hill would have taken place around February 1461, Edward issued a grant to her former father-in-law:

‘exemption for life of Ralph Botiller, knight, Lord of Sudeley, on account of his debility and age from personal attendance in council or Parliament and from being made collector assessor or taxer….commissioner, justice of the peace, constable, bailiff, or other minister of the king, or trier, arrayer or leader of men at arms, archers, or hobelers. And he shall not be compelled to leave his dwelling for war’.

Three months later Edward further granted Ralph ‘four bucks in summer and six in winter within the king’s park of Woodstock’. However Edward’s generosity evaporated on the death of Eleanor on the 30th June 1468 in a volte-face described by historian John Ashdown-Hill as nothing less than a ‘hostility’ resulting in Ralph having to surrender his properties, including Sudeley, which then went, in the main, to the voracious relatives of Edward’s bigamous ‘wife’, Elizabeth Wydeville (10).

To return to the repercussions from Eleanor and Edward’s secret, private but perfectly legal marriage:

GEORGE, DUKE OF CLARENCE’S INVOLVEMENT.

As we have seen such an explosive secret could not be kept under wraps forever and eventually rumours as well as repercussions begun to ripple out. Edward’s chickens slowly begun to come home to roost. To recap – Edward’s brother George, duke of Clarence, was a major fly in the ointment and it was, as mentioned above, certainly recorded at the time that his execution was brought about on the insistence of Elizabeth Wydeville, who having discovered she was in the awkward position of being the bigamous wife of Edward IV feared her children would lose their inheritances if George, duke of Clarence, were allowed to survive (II). This, obviously, means she knew that George had either uncovered or had been informed of the truth about the royal bigamous marriage, possibly via his closeness to Bishop Stillington or by his father-in-law, Richard Neville, earl of Warwick who was related by marriage to Eleanor. Ergo George had to go and of this she ‘easily pursuaded’ the king (12). It was also noted at the time that ‘after this deed (his brother’s execution) many people deserted King Edward’ who also ‘privately repented, very often of what had been done’ (13). Which was not surprising considering the true reason for eliminating his own brother. The Tudor historian, Vergil also recorded ‘yt ys very lykly that king Edward right soone repentyd that dede; for, as men say, whan so ever any sewyd for saving a mans lyfe, he was woont to cry owt in a rage ‘O infortunate broother, for whose life no man in this world wold once make request’ Professor Hicks gives a very good account of George’s life, trial and execution – described as a ‘judicial execution’ – in his biography of George – False, Fleeting, Perjur’d Clarence? Hicks states that George’s Act of Attainder ‘although long is insubstantial and imprecise and it is questionable whether many of the charges were treasonable, some were covered by earlier pardons, some seem improbable, none is substantiated and certainly no accomplishes were named or tried‘(14). The Croyland Chronicler, who appeared to have been an eyewitness at the trial, was clearly shocked at the proceedings and declared that those in Parliament who condemned him had been ‘misled’. He went on to clearly state that the trial was not conducted in a manner conducive to justice and that George was offered inadequate opportunity for defence: ‘No-one argued against the Duke except the king, no one answered the king except the Duke. Some persons, however, were introduced concerning whom many people wondered whether they performed the offices of accusers or witnesses. It is not really fitting that both offices should be held at the same time, by the same persons, in the same case’ (15). It was quite clearly an extraordinary and, for some, unsettling trial, with no one being surprised at the outcome. In conclusion George’s execution begs the question was the true motive behind it that he knew of his brother’s bigamous marriage and the likelihood that he might open a very nasty can of worms at any moment?

CONSEQUENCES…

What did it mean for the children of Edward and Elizabeth especially for the two sons? The sad shade of Lady Eleanor lingered on ensuring they would pay a heavy price for the sins of their father. Some historians and general commentators have made the mistake that those children of Edward and Elizabeth, importantly the two princes, born after the death of Eleanor in 1468 escaped the legal stigma of bastardisation. Also that their parents marriage somehow became miraculously valid upon the death of Eleanor – which would be the case in modern times i.e. the bigamy ends with the death of one of the superfluous spouses. Neither of these two assumptions would be correct under medieval canon law. Their marriage could only have become valid if Edward and Elizabeth exchanged vows again after Eleanor’s death, when Edward was free to do so. Which is exactly what did not happen. But their most grievous error was that their ‘marriage’ in 1464 was clandestine which prevented anyone – especially Eleanor and Bishop Stillington – from objecting to it because obviously they were unaware of it taking place. Why neither of them did so when the Wydeville ‘marriage’ was finally announced is lost to us. It has already been mentioned above that Bishop Stillington was cast into prison from 27 February to the 5 March 1478, February being the very month the trial and execution of George duke of Clarence had taken place triggered by fears the queen had that her children ‘would never succeed to the sovereignity’ unless he was ‘removed’ (16). The logical conclusion to this is that Stillington was getting severely warned into silence. Could it be that following on from this terrifying experience Stillington felt it neither safe or necessary to raise the awkward matter of Eleanor being the true and legal wife of Edward until his unexpected death and his illegitimate heir taking the throne becoming imminent forced his hand? This is pure speculation of course. As we have seen the awkward matter was known by some but had not been utilised or made public. Perhaps because there was no point in stirring up a nasty hornets nest while Edward was alive and sitting on the throne. However once he toddled off this mortal coil all would swiftly change. What of Eleanor? Sir George Buc/Buck tells us that when Lady Eleanor was told of the ‘marriage’ her husband had entered into with Elizabeth she was ‘greatly grieved and lived a melancholic and heavy and solitary life ever after and how she died is not certainly known but it is out of doubt that the king killed her not with kindness.’. This certainly does tally with what we do know about the last days of Eleanor (17). Buc also went on to describe how Eleanor’s heart was so ‘full of grief and read to burst that she could no longer conceal it ‘ and that she revealed all to a lady, who was either her sister, the duchess of Norfolk or her mother, the countess of Shrewsbury or perhaps both. Buc then erroneously says that the countess informed her husband which could not be the case as the earl had died in 1453. However if Buc was correct on Eleanor’s mother and sister being informed he may have been correct when he also said that other members of the Talbot family were then also let in on the secret which led to outrage on their part. These family members, whoever they were, confronted Bishop Stillington, who ‘knew the truth of the matter’ and who confirmed to them that this was the case as well as that it was he who had married them. Eleanor’s family members then exhorted Stillington to confront Edward. This he was too frightened to do but revealed the truth to Richard duke of Gloucester who then mentioned it to the king. The end result of this was the king flew into a rage and Stillington was thrown into prison. Assuming this is correct this could have been the stint that Stillington served in the Tower at the time of the arrest of George, duke of Clarence. Buc’s sources were Philippe de Commynes and Francis Goodwyn, bishop of Hereford (18). It’s worth pointing out that de Commynes met Richard Neville, earl of Warwick, a relative of Eleanor’s, probably whilst he was in Calais (19).

To read more about the legal aspects of the bigamous marriage of Elizabeth and Edward click here. I would also recommend reading The sons of Edward IV; A Canonical Assessment of the Claim that they were illegitimate. R H Helmholz as well as Mary Regan’s The Precontract and its Effects on the Succession in 1483 (20).

VICTIMS

In summary it can clearly be seen that there were many victims in this story. But the true culprit was not among their number although who is to say he did not bitterly regret the difficult straits he had left his 12 year old heir in as he lay wheezing his last few painful breaths. First victim and the catalyst of the ensuing tragedy was Eleanor Talbot, followed closely by the two sons of Edward, one of whom may have been Perkin Warbeck who would end his life choking at the end of a rope at Tyburn in 1499. Elizabeth Wydeville, their mother, may well be classed as another victim if she had gone through that clandestine marriage with Edward oblivious to the truth although it’s fair to say she certainly enjoyed some glory years in the interim. Yes she was queen for a while but her last years spent in Bermondsey Abbey must have been riddled with grief and disappointment.

GEORGE DUKE OF CLARENCE

George deserves a special mention on the list of victims. For him the writing was on the wall and in 1478 at a ‘parliament especially summoned, packed, and stage-managed for this purpose’ the guilty verdict was pronounced and he was sentenced to death, and silence (21). There appears to be some delay in the execution which culminated in the Speaker of the House of Commons, William Allington, lawyer (1430-79), leading ‘a group of MPs into the House of Lords and requesting that they ask the King to get on with it, insisting the execution take place without any more delay (22). Allington’s zealous approach may have been due to his confidence that there would be no backlash from Edward for forcing his hand in the execution of his brother. He had gone into exile with Edward and ‘is said to have been his standard bearer at the battle of Barnet.’ He had been rewarded by being made one of Prince Edward’s tutors and counsellors and following George’s execution on the 18 February 1478 Allington would be further rewarded. He received £300 on the 29 April, knighted May/June and on II August appointed king’s counsellor, with, for his good council on 8 July last, one third of Bassingbourne Cambs, and one third of the honour of Richmond (Yorkshire) which had been forfeited by George (23). Thus was the man who insisted the execution of George of Clarence be carried out duly rewarded. It rather flies in the face of the notion that Edward bitterly regretted the death of his brother. Well maybe, maybe…. It may be worth considering if Allington’s input was prearranged by Edward to make it appear that his hand was forced and that everybody else was to blame except for himself or could Allington have been cajoled by someone else to get a reluctant Edward to act? If so historian Thomas Penn suggests that the source of the ‘nudge could be guessed at’ noting that ‘Allington’s effusions about Queen Elizabeth were a matter of parliamentary record; the queen had rewarded him handsomely, appointing him one of the prince’s councillors and making him chancellor of the boy’s administration’ (24). Clearly either way George’s cause was lost. Even the pleas of his mother were not enough to save him. Perhaps the most charitable thing we can say about Edward was that he was ‘obliged’ to execute his own brother to save his children especially his two sons from losing everything. Which is precisely what happened.

To digress here slightly it can be seen from the above mentioned episode how much power Parliament wielded. Perhaps those that accuse Richard duke of Gloucester, later Richard III, of bullying Parliament into accepting his ‘usurpation’ of the throne should remember that Parliament was not a bunch of cissies that could be coerced into anything they did not want. Furthermore a truculent parliament could prove very troublesome for even kings especially with regards to money…

George Duke Clarence. Executed 1478. Rous Roll. Motto ex Honore de Clare.

RICHARD III

Richard through the hand he was left by his brother was more or less catapulted upon the throne having been left with no choice if he wanted to preserve his life and safeguard his remaining family. This act brought about much opprobrium and an impossible situation ending in a bloody day at Bosworth in August 1485. Whether he knew of his brother’s illicit marriage and the illegitimacy of his nephew is a moot point although it’s difficult to believe that he didn’t. However a reasonable and rational conclusion would be that he did know but in the immediate aftermath of his brother’s sudden death had not had the time to fully conclude what to do. Once Stillington stepped forward and outed the truth the matter had to be addressed and then legally finalised. The Three Estates of the Realm offered the crown to Richard at Baynards Castle and the rest is history….

Artist’s impression of the crown being offered to Richard duke of Gloucester at Baynards Castle by the Three Estates of the Realm in June 1483. Artist Sigismund Goetz. Mural in the Royal Exchange.

What of Cicely Neville, duchess of York – mother to Edward, George and Richard? She outlived all her sons and must have been privy to the truth. She too was a victim and one of the saddest. And what of the legions of men who died fighting for their king at Bosworth and those that were executed afterwards. The tragedy was not to end until the Battle of Stoke in 1487 when the last diehard Yorkists perished – along with thousands of their army – in a last ditch and futile attempt to return a Yorkist king to the throne. Such was Edward IV’s legacy.

Eleanor died, aged about 32, in 1468 while her sister, Elizabeth duchess of Norfolk, to whom she was so close, was absent from England in Burgundy attending Margaret of York at her wedding to Charles duke of Burgundy – known as ‘the Bold’. Elizabeth, who was accompanied by Humphrey, their only surviving brother, may have remained unaware of the death of her sister until her return to England. Eleanor did not live long enough to witness the turmoil spawned by her marriage to Edward and was thus spared much grief. Who knows how history would have turned out if Edward had remained true to his first and true wife.

ARMINGHALL OLD ARCH 14th century arch from Whitefriars. Eleanor’s funeral cortege would have passed through this arch in 1468. Removed from Whitefriars at the time of the Dissolution. Now in Norwich Magistrates Court.

Whitefriars monastery is now long gone another victim of the Dissolution. But this 19th century painting gives an idea of the appearance of the area, known as Cowgate, where it once stood. Whitefriars would have been situated on the eastern side of this thoroughfare betwixt the Church of St James Pockthorpe (seen in the distance) and the river. Artist David Hodgson c.1860. Now in Norwich museum.

- Domenico Mancini de occupatione regni Anglie p.45. New translation by Annette Carson.

- Talbot, John first earl of Shrewsbury and first earl of Waterford (c.1387-1453) ODNB 23 September 2004 A J Pollard

- Eleanor the Secret Queen p.81. John Ashdown-Hill

- Talbot, John, first earl of Shrewsbury and first earl of Waterford (c.1387-1453). ODNB. A J Pollard 2004.

- Elizabeth (née Woodville) c.1437-1492. ODNB Michael Hicks 23 September 2004.

- ODNB. Mowbray, John. Fourth duke of Norfolk (1444-1476). Colin Richmond. September 2004

- Domenico Mancini de occupatione regni Anglie p.47. New Translation with Introduction and Historical Notes. Annette Carson.

- Eleanor The Secret Queen p.p11. 108 John Ashdown-Hill

- Lady Eleanor Talbot; New Evidence, New Questions, New Answers John Ashdown Hill.

- Elizabeth Widville, Lady Grey p38 CPR 1461-1467, pp.72,191. John Ashdown-Hill.

- Domenico Mancini de occupatione regni Anglie p.45. New translation by Annette Carson.

- ibid.

- Croyland Chronicler p.147. Ed Pronay and Cox

- False, Fleeting, Perjur’d Clarence. George Duke of Clarence 1449-78. M A Hicks.

- Croyland Chronicler p.147. Ed Pronay and Cox

- Domenico Mancini de occupatione regni Anglie p.45. New translation by Annette Carson.

- The History of King Richard the Third p.183. Edited by Arthur Kinkaid.

- The History of King Richard the Third p.185.. Edited by Arthur Kinkaid.

- Philippe de Commynes. Wikipedia article.

- The RH Helmholz essay can be found in Richard III; Loyalty, Lordship and Law. pp 106-120.

- George, duke of Clarence (1449-1478). ODNB 2004. Michael Hicks.

- The Brothers York – An English Tragedy p.405. Thomas Penn.

- History of Parliament 1439-1509 Biographies. p.9. Josiah C Wedgwood. House of Commons 1936.

- The Brothers York. An English Tragedy p.406. Thomas Penn.

If you have enjoyed this post you might also like:

Marriage in Medieval London And Extricating Oneself Only You Couldn’t

BERMONDSEY ABBEY AND ELIZABETH WYDEVILLE’s;RETIREMENT THERE

Elizabeth Wydeville – Serial Killer?

6 thoughts on “LADY ELEANOR BUTLER/BOTELER NÉE TALBOT – THE SECRET WIFE OF EDWARD IV & CATALYST FOR THE FALL OF THE HOUSE OF YORK”