‘He had such dignity in his whole person and in his countenance such charm that, however much they might feast their eyes he never sated the gaze of observers’. Domenico Mancini

Edward V from the window at Coldridge Church, Devon.

Despite the late historian Professor Helen Maud Cam opining rather harshly “I just do not understand how people can become so upset over the fate of a couple of sniveling brats. After all, what impact did they have on the constitution?” much ink has been expended on the fates of Edward V (b.1470) and his younger brother, Richard of Shrewsbury, Duke of York (b.1473) (1). Historian Helen Maurer also pointed out ‘The unflagging fascination for mysterious murder and mayhem that lurks in the breasts of many Britons and their colonial descendants is by now well known….’ This ‘fascination‘ has led to a conviction, unshakable in some cases, that the princes disappeared ergo they must have been murdered.

Edward’s story, and that of his brother Richard, has become even more prevalent in recent times with the emergence of the Coldridge theory with its accompanying links as well as the publication of Philippa Langley’s excellent book ‘The Princes in the Tower‘ detailing the results so far of both her, and her teams, investigations. Much of these highly plausible theories, and answers, focus on what became of the princes after they had disappeared from the Tower but I want to focus here on Edward V and his life prior to 1483, the year his father, Edward IV (b.1442 d.1483) died unexpectedly and everything changed both rapidly and drastically. Not a vast amount has been recorded about his earlier years – too young was he to have made much of an impact – and from the little that is known it’s hardly possible to glean anything of much significance of his character.

Edward was born on the 2nd November 1470 in the Abbot’s House, also known as Cheyneygates, in the precincts of Westminster Abbey, where his mother, Queen Elizabeth Wydeville, had taken sanctuary following the forced leave of absence from England of her husband, Edward IV, during the Readeption of Henry VI. Elizabeth’s favourite midwife, Marjory Cobbe, was allowed entry into Cheyneygates to help the queen in her hour of need:

The second daye of Novembre was borne at Westminster in the seyntwary, my lorde the prince, the king that tyme beinge out of the lande in the parties of Flaundres, Hollande and Zelande (2).

The infant was baptised in Westminster Abbey with Thomas Millyng, the Abbot of Westminster, Prior John Esteney and Elizabeth, Lady Scrope – interestingly Margaret Beaufort’s half sister – and who had been paid £10 by the new government to attend her, or perhaps, in some measure to supervise her, standing as godparents (3).

‘Here in greate penurie, forsaken of all her friends, she was delivered of a faire son, called Edward, which was, with small pompe like any poure man’s child, christened, the godfathers being the Abbot and Prior of Westminster, and the godmother Lady Scroope,” (4).

To be brief – this post is about Edward V not Edward IV after all – the Yorkist king had made a swift exit from his kingdom – the Departure – and legged it over to Flanders after the Lancastrian king, Henry VI, had been, briefly as it would transpire, returned to the throne – the Readeption. However according to the Croyland Chronicler Edward was back by the middle of Lent 1471 – the Arrival – and asap went to Cheyneygates to meet his new son. ‘Greetings my darling boy’ he said as he clutched the gurgling infant to his chest. I made that last bit up – obviously – but I’m pretty sure something on these lines would have been uttered in private. The official announcement was ‘The great bounty of our Lord God has pleased to send unto us our first begotten son, whole and furnished in nature, to succeed us in our realm of England, of France and Lordship of Ireland for which we thank most humbly his infinite magnificent’. Moreover the prince was God’s ‘precious visitation and gift and their most desired treasure’ (5). After the birth of three daughters, Elizabeth, Mary and Cecily, the relief of the parents must have been palpable on the arrival of an all important son. As explained by historian Michael Hicks: Up to now his (King Edward’s) heir presumptive was the princess Elizabeth whom he had promised in marriage to Montague’s son, George Neville. But daughters offered no stability or continuity. They could not reign, so contemporaries supposed, nor could they rule, govern or command obedience, wage war or fight. For a king to leave only daughters promised at the very least, the conveyance of the crown to a husband, if not to the scion of a faction, like George Neville, then most probably a foreign potentiate and worse, diversion and Civil War. The birth of the son in contrast foretold an undisputed and indisputable succession. Prince Edward’s birth prolonged the house of York well beyond his father’s lifetime, promised continuity to the Yorkist dynasty and all it stood for and eased any fears and doubts about what would happen when king Edward died….’

Anyway the king was so delighted that anyone who had aided Elizabeth and his children during their sojourn at Cheyneygates were not forgotten and generously rewarded including a kindly London butcher, John Gould, who had kept the queen’s party in meat i.e. ‘half a beef and two muttons a week for the sustentation of her household’. (6)

By June 1471 the infant Edward had been created Prince of Wales and Earl of Chester as well as Duke of Cornwall.

‘By the time he was eight months old he possessed his own chancellor, chamberlain (the ever loyal SIr Thomas Vaughan/Vaghan who remained in that position until the events of 1483 overtook everyone) and a steward of his household as well as his own council to administer his estates up to the age of fourteen’.. His letters patent and the inscription on his great seal were in the name of ‘Edward first begotten (primogenitus) son of the last king of England and France, King Edward the fourth Prince of Wales, Duke of Cornwall and Earl of Chester‘ and were dated by the regnal years of ‘his dread Lord and father’ (7).

When Edward was but three years old he departed from the bosom of his family to live in his own household at Ludlow Castle, now in Shropshire, but then in the Welsh Marches. We can only speculate on the feelings of his mother as she bid her small son farewell. But he was the Prince of Wales so there you go. Possibly the queen’s sadness was assuaged by the birth of a second son, Richard, Duke of York, in the same year of Edward’s departure to Ludlow. A third son born in 1477, George, Duke of Bedford, would not survive infancy.

Ludlow Castle with Dinham Weir from the South West c.1765. Artist Samuel Scott

Evocative photo of Ludlow Castle today. Photo with thanks to Ian Capper. For more photos of Ludlow Castle scroll to the end of post.

The Yorkist royal family were now, in the main, on a roll with an ever burgeoning nursery of offspring. There were a few hiccups along the way of course, such as the judicial murder of Edward’s uncle, George duke of Clarence, on the 18 February 1478. This execution, it has been said, was down to the insistence of Edward’s mother, Elizabeth Wydeville, who had reason to believe that Edward Jnr’s future inheritance – as well as that of his siblings – was threatened by uncle George more than likely because he was in possession of the dangerous secret that Edward’s parents marriage was invalid. It had transpired that Edward was already a married man/king when he married Elizabeth and of course it was impossible, legally anyway, for him to be married to two women at the same time. Elizabeth was concerned that George might be letting that particularly nasty cat out of the bag at some time soon in the future. Mancini noted that the Queen, ‘mindful of the insults to her family and the imputations laid to her charge, namely that according to established custom she was not the legitimate wife of the king, deemed that never would her offspring by the king succeed to the sovereignty unless the Duke of Clarence were removed and of this, she easily persuaded the king himself’ . Indeed the Wydville family en masse were held responsible for the duke of Clarence’s death (8).

Edward V’s mater Elizabeth Wydeville, Royal Window Canterbury Cathedral, North Transept.

How much, if any, of the rather alarming news of his uncle’s execution was relayed to Edward, then aged about seven years old, is unknown. However the fact could not have been avoided forever that he was now blatantly minus an uncle. Parents down the centuries have long been aware that little pitchers have big ears and it’s possible that he may have had an inking that something unpleasant had befallen Uncle George. Whether or not he knew why, he would certainly find out later in the summer of 1483 when, his parents rather sordid chickens finally came home to roost. It was then his young life, as he knew it, imploded and changed forever.

But back to Ludlow Castle. It was there, in the main, Edward would spend the next decade although occasions were recorded when he was with one or both of his parents. I’ll return to that later. A group of men of fitting importance and status accompanied him to ensure that he was raised as the heir to the throne should be. The main man in this clique was Edward’s Wydeville uncle, Anthony, second earl Rivers who has been variously described as ambitious, magnificent and scholarly, hardheaded and businesslike and an agreeable man; serious and upright who had been tested all his life, whatever his condition, had obliged many and disobliged none (9). As Hick’s points out River’s position would later place him in a strong position to influence developments in the wake of Edward Snr’s sudden demise on the 9 April 1483 and the succession of Edward Jnr.

Of these men an important constant in Edward’s life would have been his chamberlain, Sir Thomas Vaughan (d.1483). Vaughan, a Welshman, had been appointed a member of the prince’s council on the 8th July 1471 ‘and was prominent in supervising his estates’ and his upbringing mostly remaining by his side throughout the next decade of his life (10). Before the mini prince had mastered walking Vaughan would carry him in his arms at important events and even beyond when, aged almost two years old, he carried him to pay his respects to his father’s guest, Louis de Gruthuyse/Gruuthuse on both the 12th and 13th October 1472 (the 13th being St Edward’s Day) on the last occasion swathed in his ‘robes of state’ (11).

Vaughan was knighted on the 18th April 1475. He was either granted or allowed to build a house close to Westminster Palace in the Abbey precincts, which became known as Vaughan’s House, where he would stay with Edward when the prince visited his parents in London (12). Edward may well have come to regard Vaughan as a father figure to replace his own in absentia parent. The sudden and dramatic turns of events that followed at both Northampton and Stony Stratford in late April 1483 when Vaughan was abruptly removed from his side and later, along with his maternal uncle Earl Rivers and half brother Richard Grey, executed at Pontefract, after a trial presided over by the Earl or Northumberland, must have been both devastating and terrifying for a young lad who up until then had led a cocooned and cosseted life (13). Sir Thomas Vaughan was buried in St John the Baptist’s chapel, Westminster Abbey. Sadly his altar tomb was badly vandalised in 1808 when it got in the way of the building of a new Cecil vault resulting with one side and one end being removed as well as the arcade where the monument stands sliced into (14). The Latin inscription is now missing but was recorded in the 1680s:

‘Thomas Vaughan, treasurer to King Edward the fourth and chamberlain to his first born son. Rest in Peace. Amen’

Sir Thomas Vaughan’s altar tomb, still standing but much damaged. Chapel of St John The Baptist, Westminster Abbey. Photo thanks to Westminster Abbey.

APPEARANCE

We are now able to tell, thanks to a recent discovery of a medieval manuscript by historian Dr J Laynesmith which included an image of Edward’s paternal grandfather Richard Duke of York (1411-1460) that both bore a striking resemblance to each other.

Richard duke of York. Wigmore Abbey Chronicle and Brut Chronicle. Special Collections Research Centre, University of Chicago Library.

Edward’s portrait from the window at Coldridge Church, Devon.

This resemblance does not seem quite so pronounced in portraiture of Edward’s father :

Edward IV. Royal window, Canterbury Cathedral, North transept.

We are also very fortunate that as an aid to conjuring up an image of Edward Jnr we have two surviving accounts describing some of his clothing. The earliest one would be no later than November 1472:

Five doublets, price 6s 8d, two of velvet, purple or black and three of satin, two being green or black,

five long gowns, price 6s 8d, three being satin, purple black and green and others of black velvet;

two bonnets, price 2s, one of purple velvet lined with green satin and the other of black velvet lined with black satin,

and a long gown cloth of gold on damask priced £1 (15).

The second account dates from September 1480 and is contained in the Wardrobe Accounts of Edward IV:

‘To the righte highe and right myghty Prince Edward by the grace of God Prince of Wales Duke of Cornwayle and Earle of Chester, the firstbigoten son of oure said Souverayn Lorde Kyng Edward the iiijth, to have of the yift of oure Souveraine Lorde the Kyng, v yerdes of white cloth of golde tissue for a gowne, by vertue of a warrant undre the Kinges signet and signe manuelle bearing date the xvij day of August in the xxth yere of the moost noble reign of our said Souveraine Lorde the Kyng unto the said Piers Courteys for the deliveree of the said clothe of gold directe,

White clothe of gold tissue, v yerdes (16).

CHARACTER

Of course it is quite impossible to be able to assess his character from the scant references we have. Can we form an opinion from the comments made by Domenico Mancini that he was ‘especially accomplished in literature, so that he possessed the ability to discuss elegantly, to understand fully and to articulate most clearly from whatever might come to hand, whether poetry or prose, unless from the most challenging authors. He had such dignity in his whole person and in his countenance such charm that, however much they might feast their eyes he never sated the gaze of observers’ (17).

Might also the additional instructions given in the 1483 ordinances also indicate that at times the young prince was misbehaving perhaps even getting too big for his little boots? I would love to think so. The king instructed that his son was not to issue orders for anything to be done before taking the advice of John Alcock, Richard Grey or Earl Rivers. If he did attempt to do so he was to get three warnings which if unheeded he was to be reported to his father.

Mancini also noted that he was ‘much like his great father in spirit’.

Is that enough to form a rounded opinion of his character. Sadly not. Yet it’s nice to think he was spirited enough to play up now and again – enough to get his father to comment upon.

HEALTH

It has been suggested that Edward was not a healthy child and may have even succumbed to a natural death in 1483. This impression may have arisen from the knowledge that his physician, Dr Argentine, visited him during his stay in the Tower in the summer of 1483. However the doctor found him in a depressed state of mind, perfectly understandable following the traumatic events that had just taken place, rather than physically ill – something which Dr Argentine would not have failed to mention had that been the case. This low mood that Edward was in – also mentioned in the Gelderland Document – has been over egged by suggestions that he was melancholic by nature although there are no primary sources, as far as I know, that state this. The late Dr John Ashdown-Hill suggested in his book, The Mythology of the Princes in the Tower, that from the way Edward IV worded his will, Edward Jnr may have been considered fragile – in infancy at least – and not expected to survive. However even if this were the case his health may have picked up as he grew older. Certainly he was a well travelled youngster which does not imply he was sickly. However in the interest of clarity lets look at what Dr Ashdown-Hill wrote on the matter:

‘In his will drawn up in 1475 King Edward IV refers to ‘oure son Edward the Prince or such as shall please Almighty God to ordeigne to bee oure heires and to succede us in the Corone of England’.

Dr Ashdown-Hill took this to mean that the king had the notion his son might predecease him and indeed it’s possible in those times of high child mortality this may have been the case at the time. Dr Ashdown-Hill also mentioned the Colchester Oath Book which says that Edward V was known to be dead (of natural causes) by the end of September and the beginning of October 1483. However this seems odd in the light of it having been recorded in the Great Chronicle of London that ‘duryng this mayris (Edmund Shaa) yere (the mayoral year in question ended on the 29th September) the childyr of king Edward were seen shotyng and playyng in the Gardyn of the Towry by sundry tymys’ which seems odd behaviour for a child that was about to keel over and die at any moment (18). Certainly the Croyland Chronicler, writing his version of events later in 1486, believed Edward, and indeed Richard, were still alive in September. Hostile to Richard he would have liked nothing better than to poke an accusing finger at him if he had heard even he slightest whisper that Edward (and his brother) had died (or been murdered) in September. Instead while complaining about the ‘splendid and highly expensive‘ feasts and entertainments that took place in York throughout the first half of September 1483 during the course of Richard and Queen Anne’s visit he noted ‘in the meantime and while these things were happening, the two sons of King Edward remained in the Tower of London…..

As mentioned above it should also be taken into account that Edward was a regular traveller. Hicks tells us that:

He was with the king at Windsor in May 1474, in April and at midsummer, in company with his mother and Cardinal Bourchier at Windsor on 18th of August 1477, at Westminster for the Great Council from 9th of November 1477 and thereafter at the Parliament of January – February 1478, at The More in Rickmansworth on 19th of May and with the king in November 1478, with him in May 1479, with both his parents from November at Woking, for Christmas, and at Greenwich on 30th December 1479, at Greenwich with the king on 16th of July 1480, with the king in February, May, August and in the winter of 1481 and with both parents for Christmas 1481 at Windsor, Christmas 1482 at Eltham (19).

Philippa Langley also mentions he travelled to Warwick to meet his uncle George, Duke of Clarence in 1474 as well as visits to Haverfordwest, A visit with his mother to Canterbury in early 1483 was cancelled due to an outbreak of measles.

Note that some of these journey were made in the midst of winter – surely not a good idea if indeed Edward was frail.

Finally we have Mancini’s comments – which I will return to later – about the vigorous ‘exertions’ and activities that Edward took part in at Ludlow which perhaps would have been surprising if he had been in poor health. Weighing it all up I remain unconvinced that Edward suffered from poor health.

EDUCATION AT LUDLOW

The task of shaping the young boy into a good Christian Prince and future King, preferable one with Wydeville leanings, was given to his maternal uncle, Earl Rivers, who became the Prince’s Master. To press this point home he gave himself the title ‘Anthony Wydeville, Earl Rivers, Protector and Defender of the rights of the Papacy in England, Governor of the Lord Edward Prince of England, first born of the most illustrious Prince Edward IV King of England, Lord of Scales, Nuchelles and the Isle of White’ (20). He was led in his momentous task by ordinances drawn up by the Prince’s father in September 1473 – to be updated when he reached the age of twelve. He was to ‘guide and oversee that all the princes servants now being and hereafter do duly and truly their service and office‘ as well as they were to ‘assist, aid, and obey Earl Rivers (21). Naturally. Nothing was to be left to chance and consequently a detailed schedule was helpfully drawn up:

The prince arises from his bed (Hicks suggests this was possibly 6 am)

Matins in his chamber.

Breakfast.

Mass with his household in the chapel.

School ‘such virtuous learning as his age shall now suffice to receive’.

Dinner, ‘then to be read before him noble stories’.

More school.

Recreation and exercises.

Supper.

Evensong in his chamber.

Recreation to make him ‘joyous and merry’ about going to bed

8 pm bed.

No doubt the recreation and exercise were part and parcel of him being ‘indulged in horses and dogs and other youthful exertions to build bodily strength’ (22). No little couch potato was he!

The prince also had his own almoner, Dr Davison, Dean of Salisbury and Windsor, confessor, and chaplains. His Latin teacher was John Giles who may have been the same tutor who taught him French.

APRIL 1483

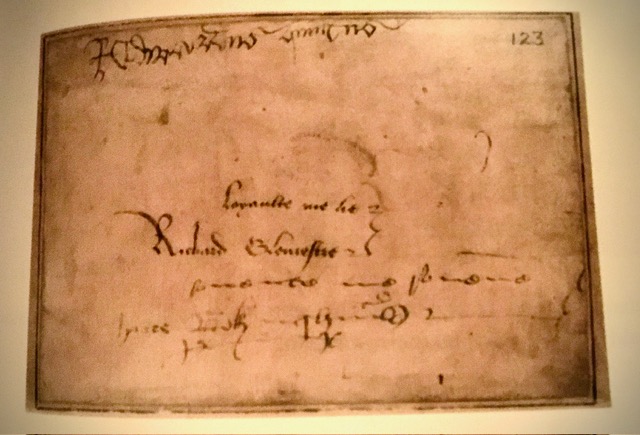

And so we have reached the point in Edward’s life where his father suddenly and unexpected departed this life leaving him, at that point, in the control of his Wydville relatives mainly Anthony, Earl Rivers. Thus begun the train of pivotal events which begun at Northampton and Stony Stratford and which have been well recorded elsewhere. If you are interested in delving more fully into this part of Edward’s story I highly recommend Annette Carson’s in-depth article which can be found here. At some point in the journey to London, which must have been at best awkward and at worse extremely tense – bearing in mind trailing in its wake were four wagons loaded with arms bearing the devices of the queens brothers and sons with criers who made it known throughout the crowded places wherever they went that these arms had been assembled by the Duke of Gloucester enemies and stored at convenient locations outside the city with the intention of falling upon the Duke and killing him as he came in from the outline district – the two dukes took the time to try to distract the young king from the recent drastic and momentous events that had just taken place (23). A piece of parchment has survived which bears all three signatures plus the mottos of the two dukes. At the top is the signature of the young king, followed by Richard’s with his motto ‘Loyaulte me lie’ (Loyalty binds me) and Harry Buckingham’s ‘Souvente me souvene’ (Remember me often). How the conversation, and who instigated it, led up to this moment which may have been an attempt to mollify Edward, we can only speculate. But it does remain, in a tragic story, a rare human touch.

The parchment with mottos. 1483. BL, MS Cotton Vesp. F xiii, f. 123. Now in the British Library.

When eventually the party reached London, Edward initially stayed in the Bishop of London’s palace:

‘And so from thens brought hym unto London; and the iiijth day of May he cam thrugh the Cite, ffet and met by the Mayr and Citezeins of the Cite at Harnsey (Hornsey) park, the kyng ridying in blew velvet and the Duke of Glowcetir in blak cloth, like a mourner, and so he was conveid to the Bysshoppys Palaes in London, and there logid’ (24).

The Croyland Chronicler, as per usual hostile to the Duke of Gloucester, prudently omitted the four wagons of Wydeville arms but described later events:

‘All the Lords spiritual and temporal and the mayor and aldermen of the city of London were compelled to take the oath of fealty to the king. Because this promised best for future prosperity it was performed with pride and joy by all. Discussions had already begun there and had gone on for some days when there was talk in the Great Council about the removal of the king to some other, more spacious, place; some suggested the hospital of Saint John, some Westminster, but the Duke of Buckingham suggested the Tower of London and his opinion was accepted verbally by all.’ (25).

Buckingham’s suggestion the best place for Edward to reside was in the royal apartments at the Tower of London would not have been considered untoward as the Tower was the customary place of residence for royalty to stay prior to their coronations and from where they would set out. Arrangements for the coronation, the date of which had been put back, were still ongoing when the shocking realisation that Edward’s parents marriage had been invalid changed everything yet again. See Titulus Regius (The Royal Title)

And I will leave the story at this point as the train of events which led to the cancellation of Edward’s coronation and his later mysterious disappearance have been well documented in great detail elsewhere. In summary, although there is some information to be found on his day to day lifestyle, what we do know about the young Edward does not cast much, if any, light on his actual character aside from Mancini’s comment that he resembled his father in spirit. What is clear is there seems to have been at no point that Edward was ever in control of his own life. Which to be honest is not unusual for a youngster especially a royal one. However if the Coldridge theory is barking up the correct tree then it would also apply to his adult life too. For those of you who have not read any of my earlier posts regarding the Coldridge theory and importantly the further links including Sir Henry Bodrugan’s role, Gleaston Castle, the Yorkist Rebellion of 1487, Edward’s survival and presence at the Battle of Stoke you will find the links below the notes. Below are more pictures of Ludlow Castle.

Window seat overlooking the 12th century Chapel. Photo thanks to Pinterest.

North Range and Round Chapel dedicated to St Mary Magdalene. Photo thank you essentially-england.com

Rear Gate House. Photo thank you essentially-england.com

The Gate House. Photo thank you essentially-england.com

Interior of the Great Chamber block. Photo essentially-england.com

Interior view of the Great Keep. Photo with thanks to castlewales.com

Photo essentially-england.com

West Doorway into the 12th century Chapel dedicated to St Mary Magdalene. Photo Welsh Castles.

Whodunit? The Suspects in the Case. Helen Maurier. Article in Ricardian Register 1983. Notes (1): Quoted by Charles T. Wood, “The Deposition of Edward V,” Traditio 31 (1975), p. 286. For an account of the origin of Cam’s remark, see Charles T. Wood, “In Medieval Studies, is ‘To Teach’ a Transitive Verb?” Studies in Medieval and Renaissance Teaching, 3(2), fall 1992

- Grants of Edward V, p.vi, note b. G J Nichols. Elizabeth Woodville A Life. Notes p. 210. David McGibbon.

- Elizabeth Woodville, Mother to the Princes in the Tower p.43. David Baldwin.

- Holinshed’s Chronicle. Vol. 3. p. 300 c.1577

- Public Records Office, Kew. C66/532 m.15. See p.55. Hicks

- Elizabeth Woodville A Life p.85 David McGibbon

- Edward V The Prince in the Tower p.55. Michael Hicks.

- Domenico Mancini de occupatione regni Anglie pp.45. 49. New translation with historical notes by Annette Carson.

- The Mystery of the Princes p.28. Audrey Williamson, Woodville/Wydeville, Anthony, second Earl Rivers. (c. 1440–1483) Michael Hicks ODNB 23 September 2004 and Domenico Mancini de occupatione regni Anglie p.49. Annette Carson.

- ODNB Vaughan, Sir Thomas (d.1483) R A Griffiths

- C L Kingsford English Historical Literature in the Fifteenth Century: The Record of Bluemantle Persuivant p.p. 379-88. See also Elizabeth Woodville, A Life p.p.97.98. David MacGibbon.

- https://biography.wales/article/s-VAUG-THO-1483.

- Historia Regum Angliae pp213-4. John Rous, Translated by P Hammond and Anne F Sutton. See their book Richard III The Road to Bosworth p.III.

- Memorials of the Wars of the Roses p.118. W E Hampton.

- Edward V The Prince in the Tower p. 63. Michael Hicks

- Wardrobe Accounts of Edward the Fourth 18th April to the 29th September 1480, 160. Nicolas Harris Nicolas, Esq., 1830.

- Domenico Mancini de occupatione regni Anglie. p.65. New translation with Introduction and Historical Notes by Annette Carson. 18

- Richard III, The Road to Bosworth Field p.144. P W Hammond and Anne F. Sutton.

- Hicks p.66

- Hicks p.76

- Hicks p.75.

- Domenico Mancini de occupatione regni Anglie. p.49. New translation with Introduction and Historical Notes by Annette Carson.

- Ibid 59.

- Chronicles of London p.190 (ed. Kingsford)

- The Crowland Chronicle Continuations 1459-1486 p. 157. Edited by Nicholas Pronay and John Cox.

- Domenico Mancini de occupatione regni Anglie p 55.. New translation with Introduction and Historical Notes by Annette Carson.

- Ibid.

A Portrait of Edward V and Perhaps Even a Resting Place?- St Matthew’s Church Coldridge

SIR HENRY BODRUGAN; A LINK TO RICHARD III, EDWARD V, COLDRIDGE AND THE DUBLIN KING

THE MYSTERIOUS DUBLIN KING AND THE BATTLE OF STOKE

3 thoughts on “EDWARD V – HIS LIFE PRIOR TO JUNE 1483”