*This is the title of a chapter from The Princes in the Tower by Philippa Langley. Without the aid of this invaluable book I would never have been able to write this post…

The Gelderland Document is a unique, tantalising and quite astonishing document that was discovered back in the 1950s in the Gelderland Archives situated in the Netherlands. It was sent by Mr P J Mey, The Master of the Charters, to Dutch historian Professor Diederick Enklaar at the University of Utrecht for his perusal and appraisal. Unfortunately the Professor appears to have given it scant interest, remarking ‘Is the case of the false York ‘Perkin Warbeck’ not already sufficiently known?” (1). Yikes! Perhaps he was busy with other things that day. Due to Professor Enklaar’s rather lacklustre response it appears Mr Mey became disheartened, with the result that this intriguing document was once again stored away, without any further appraisement and its existence forgotten about up until recently. Now thanks to a member of Philippa Langley’s Dutch Research team – Nathalie Nijman-Bliekendaal – it has now re-emerged once again and given the attention it deserves. Philippa, who spearheaded the search and recovery of the remains of Richard III, has given an in depth assessment of the document with researcher Nathalie in her book ‘The Princes in the Tower’ which I would recommend to anyone with an open mind who is willing to cast aside old outdated beliefs and who wants to delve further into the fates of the missing princes and explore the very real likelihood that they both survived the reign of their uncle Richard III. However back to the document which, fortunately being located in the Netherlands, was thus out of reach of Henry VII’s Human Shredders I give here just a brief résumé of its contents:

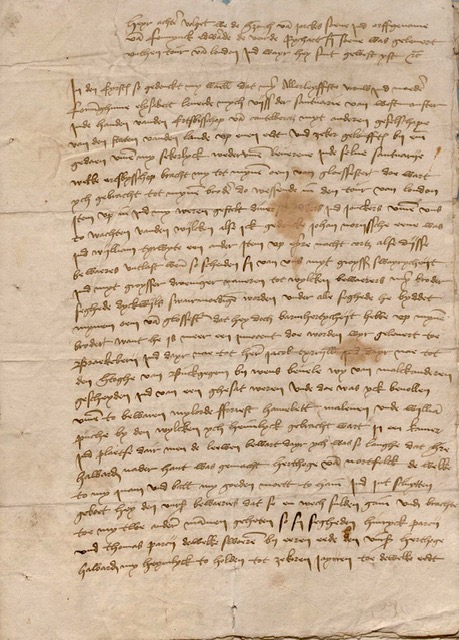

The title is written in the third person but the narrator of the document is given as ‘the Duke of York, son and heir of King Edward IV, Richard’ Richard, also known as Richard of England, has made a four page statement, dictated to a scribe, describing the chain of events after his mother, Elizabeth Wydeville ‘my dearest lady and mother, queen elysabett/Elizabeth ‘delivered me from the sanctuary of Westminster’ to the Archbishop of cantelberch/Canterbury and others after which he was taken to ‘my uncle of gloessester’/Gloucester. Following on from the meeting with his uncle he was then taken to join his brother, Edward V, then residing in Tower of London. He mentions John Norris and William Tyrwyth as waiting for him there to meet him although they left by the next night. The short time spent together by the little group must have been pleasant for Richard recalled on their departure feelings of sadness and melancholy as well as how to these guards ‘my brother often said melancholic words’ including that he ‘prayed my uncle of gloessester to have mercy on him as he was an innocent person’. Now this is extremely interesting because these feelings of angst and sadness on the part of the young Edward are borne out by his physician Dr Argentine, who visited him in the Tower and who later relayed them on to Dominic Mancini who in turn recorded them in his report de occupatione regni Anglie (2). Edward’s bewilderment and apprehension were perfectly understandable when it’s recalled how he had been so recently treated as a reigning king on the verge of his coronation, with all the reverence that entailed, and had now been informed everything had changed.

Next both the boys were introduced to ‘Braekeberij‘/Brackenbury, who was Constable of the Tower at that time and renowned for his integrity. Sir James Tyrell was also introduced to them as well as the Duke of Buckingham. The latter instructed that the boys be separated. Richard was taken by lords Foriest, Hamelett Maleven (Halneth Mauleverer?) and William Puche to the place where the lions were kept ( the now demolished Lion Tower?).

The area of the Lion Tower to the west of the main part of the Tower of London. Now demolished. Out of the way and with easy access to the Thames. Illustration from a Survey made in 1597 by W Haiward and J Gascoyne.

After being there some time he was visited by the ever reliable John Howard (1425-1485) duke of Norfolk who ‘encouraged‘ him and brought two men with him i.e. Henry and Thomas Parcij. These two men swore under oath to Norfolk that they would take Richard, supervise him and hide him ‘secretly away for certain years’. They then shaved his head and gave him ‘poor and drab’ clothing to wear. Philippa has noted the astonishing coincidence that Howard recorded the purchase of clothing for ‘humble children of the stables’ in his accounts on the II August 1483 (3). It comes as no surprise that Howard should have been chosen by the king for a role that required the most trustworthy and able of men to carry out. Howard was such a man. Described by Paul Murray Kendal as a man who remained true to his Essex roots, plain, solid, tough, a careful householder with a generous heart, a lover of Colchester oysters and of the sea from which they are ripped’. ‘The sea was his element‘ and his were the perfect pair of hands to task in getting the young Richard out of England and over the sea to France. Anne Crawford, Howard’s biographer, described him as ‘an extremely versatile royal servant, as a soldier, administrator and diplomate he had few equals among his contemporaries’. He did not fail his king in this sensitive matter but died with the secret still intact when he fell at Bosworth in August 1485. The identity of the Parcijs is still under investigation at this moment in time.

John Howard. Painting of a stained glass image formerly at Tendring Hall or the South Chapel, Stoke by Nayland Church, now lost.

Richard described how he was then taken to board a boat which duly arrived at Boulogne-sur-Mer and from there to Paris. He stayed in Paris for a long time until, being noticed by English folks, he was taken to Chartres, and from there to Rouen, to Dieppe and finally arriving at Hainault. Brabant, Malines, Antwerp and Bergen were also on the itinerary with a prolonged stay at the latter. Edward Brampton’s wife then makes an appearance being described as ‘ready to sail’ with Richard and the Parcijs to Lisbon. Edward Brampton was Portuguese and of the Jewish faith later converting to Christianity and sponsored by Richard’s late father, Edward IV. He was knighted by Richard’s uncle, Richard III, the first man born of Jewish faith to receive the honour.

Here clearly were a couple that had links to the Yorkist regime and would have been comfortable with finding their way around Portugal and a suitable place for the young Richard to reside undetected. While in Lisbon Richard, then aged about 14, was able to send one of the Parcijs, Thomas, to England with messages for his mother who by that time had been sent to ‘retirement’ in Bermondsey Abbey. It was about this time Henry Parcij fell fatally ill with the plague. To add credence to the story it is a known fact that the plague was raging at the relevant time in Lisbon (5). While Henry lay ill he told Richard that when he died, he was to get himself to Ireland to the lords of Kyldare and Desmond. After advising Richard how he ‘should rule the country’, Henry died. Richard duly went to Ireland where he was recognised ‘for who he was‘ and treated as such by the lords including Kyldare and ‘gylbart de braven‘/Garret the Great.

During his stay in Ireland Richard was contacted by the King of France, Charles VIII, who made a firm promise to him to ‘assist and help me to claim my rights’. However upon his arrival in France, following a treaty between the French king and Henry VII where both sides promised not to support any claimants or rebels of the other, those promises proved to be hollow and so Richard travelled to his ‘dearest‘ aunt, the Duchess of Burgundy. ‘She recognised my rights and honesty. And by the grace of God, I received help, honour and comfort from my dear friends and servants that in a short time I will obtain my right to which I was born.... (6).

Here the statement ends.

Philippa and Nathalie’s appraisal of the statement makes interesting reading pointing out how the heading of the document written in the third person but in the same handwriting of the duke’s narrative leads them to believe that it’s a copy of an original document when a scribe wrote down the words dictated to him by Richard. Several copies may have been made of the original and distributed ‘throughout Burgundy” in an effort to get the important news of the survival of Margaret duchess of Burgundy’s nephew disseminated. As Richard was ‘unreservedly recognised‘ as Richard duke of York, Edward IV’s son, in Burgundian Netherlands, the authors point out this strategy appears to have worked. Richard’s recognition as the son of Edward IV is further enforced by the fact that King Maximilian – Margaret’s late stepdaughter’s husband – supplied both military and financial support as well as, recent archival searches have revealed, several other people of high rank also giving financial aid to Richard. These included Albert of Saxony and Englebert II of Nassau who lent him 30,000 gold florins and 10,000 gold ecus respectively which Richard promised to pay back once he had regained his throne. That people were willing to lend such massive amounts makes it clear that in Burgundy he was indeed believed to be the true son of the late Edward IV.

Ah! some of you may say …… but it could easily be a fake document perhaps to enable a ‘Pretender’ to make a play for the throne of England. However the comments made by Richard about Edward V’s state of mind correlate with those made by Dr Argentine on the same subject as does the poor and drab clothing given to Richard to wear with the purchase of the clothing for the poor children of Norfolk’s stables and the outbreak of plague in Lisbon at the precise time that Henry Parcij succumbed to it. These correlations cannot all be purely coincidental and lead to the conclusion that the document is the real deal. There is also the small point, but worth mentioning, that would a Pretender and his co-plotters have been familiar with the layout of the Tower of London and that the small tucked away Lion Tower was the perfect place to park a prince for a while? We also have the sumptuous Tournament Tapestry which affirms that Richard of England was recognised and accepted by the Burgundian nobility.

The Tournament Tapestry was commissioned by Frederick the Wise and depicts high ranking members of Burgundian Society. including Margaret of Burgundy and her nephew Richard. You can read more about the tapestry here.

Margaret Plantagenet, Duchess of Burgundy from the Tournament Tapestry of Frederick the Wise c.1490. South Netherlands. Musée des Beaux-Arts de Valenciennes, France. Photo Nicholas Roger.

Margaret of York, duchess of Burgundy as a young woman. Unknown artist.

Richard of York. From the Tournament Tapestry of Frederick the Wise c.1490. Note the blemish above the eye.

We know that Richard duke of York’s attempt at claiming the throne of England was doomed resulting in disaster, tragedy and a terrible death for him at Tyburn. Letters written by Maximillian to the Council of Flanders begging them to intervene and appeal to Henry for Richard to be spared and released as well as a letter from Margaret duchess of Burgundy directly to Henry apologising and promising her future good behaviour were of no avail (7). We don’t know the thoughts of his sister, Elizabeth of York, or how she dealt with them, as the awful events unfolded which even the most pragmatic would have found onerous to deal with. However it’s difficult to believe she could have been oblivious to the true identity of the young man who has gone down in history as ‘Perkin Warbeck‘.

You can find out more about the findings of Philippa Langleys Missing Princes Project and the Gelderland document here.

- The Princes in the Tower, p.190. Philippa Langley

- Domenico Mancini de occupatione regni Anglie p.65. New Translation with Introduction and Historical Notes by Annette Carson.

- Howard Books Vol.2. p.426.

- Richard III p.201. Paul Murrey Kendall

- The Princes in the Tower p.438. Notes. Philippa Langley

- The Princes in the Tower, p.208. Philippa Langley.

- Perkin a Story of Deception p.430 and 471. Ann Wroe.

If you liked this post you might also be interested in:

PERKIN WARBECK AND THE ASSAULTS ON THE GATES OF EXETER

Lady Katherine Gordon; Wife to Perkin Warbeck

A PORTRAIT OF EDWARD V AND THE MYSTERY OF COLDRIDGE CHURCH…Part II A Guest Post by John Dike.

GLEASTON CASTLE – RENDEZVOUS FOR THE YORKIST REBELS IN 1487?

One thought on “THE GELDERLAND DOCUMENT – ‘PROOF OF LIFE OF RICHARD, DUKE OF YORK’* ALIAS PERKIN WARBECK”