A delightful artist’s impression of ‘Richard Whittington dispensing his charities’. Artist Henrietta Ray before 1905 oil on canvas. Royal Exchange, London.

Even the most disinterested in history children would recognise the name ‘Dick Whittington’ and also his best, and only friend, his cat, most of them being familiar with the rather delightful folk story, which dates back to the 17th century, as well as perhaps even more so, the pantomime. As they watch and excitedly yell ‘Behind You. … !’ etc., they are probably unaware that Richard Whittington was a real man who lived in medieval times and although sadly he did not have a cat he did much good and the results of his benevolence still, astonishingly, survive up until today.

Richard Whittington (c.1350-1423) was born in Pauntley Court Manor House in the small village of Pauntley , Gloucestershire and presumably he was baptised in the parish church there, St John the Evangelist. He was the son of Sir William Whittington d.1358, a landowner and Joan Maunsel (1).

Pauntley Court Manor house today. It was here that Richard Whittington was born c.1350

St John the Evangelist Church, Pauntley, Gloucestershire. It’s highly likely Richard was baptised in this ancient church.

It is said Richard’s father was experiencing some financial difficulty but, in any case, being the third and youngest son and thus highly unlikely to stand much chance of coming into a useful inheritance, he was apprenticed at an unknown date to a London mercer. The mercers of those times dealt with the wonderful luxurious fabrics worn by the nobility and well to do: silk, linen, fustian, worsted, and luxury small goods, and the wealthiest of the trade expected to participate in the export of English wool, woollen cloth, and worsted, and to import the other merceries (2). While some young men may have ended up bitter, twisted and truculent by being sent away from their families to take up a trade instead of effortlessly inheriting the family jewels, young Richard seems to have taken to it like a duck to water becoming very proficient in his trade but perhaps it is more a modern trait to endlessly whinge about how unfair life can be and how hard done by you are. He supplied his luxury goods to members of the royal court and in doing so he became a favourite of King Richard II. These members of the nobility included John of Gaunt, Thomas of Woodstock, Henry Bolinbroke (the future Henry IV), the Staffords and ‘royal favourite Robert de Vere to whom he supplied nearly £2,000 worth of mercery’. The king himself now turned to Richard to supply his wants and needs. Initially it was quite modest buys including in 1389 £11 for two cloths of gold which the king gifted to two knights who had come down from Scotland as messengers. However in 1392-4 Richard’s career as a mercer was on a roll when he sold goods worth £3,474 16s 8 and a half pence to the Royal Wardrobe. These goods included velvets, cloths of gold, damasks taffetas and gold embroidered velvets. Richard Whittington had arrived as they say. Anne Sutton wrote that Richard II and his uncle Thomas of Woodstock were perhaps Richard’s most profit spinning customers. Clearly the goods Richard supplied – some of which were from Italy – must have been exquisite and he has been described by Caroline Barron as a ‘connoisseur of works of craftsmanship’. When Bolingbroke took the throne as Henry IV, Richard would continue to supply Henry’s court with luxury wares. These would include some of the sumptuous fabrics required for the marriages of the king’s daughters Philippa and Blanche such as ten cloths of gold for Blanche’s marriage at a total cost of £215 13s 4d and pearls and cloths of gold costing £248 10s 6d for Philippa’s nuptials.

Besides providing wonderful things he also made many loans to Richard II as well as Henry IV and his son, Henry V. At the time Richard II was evicted from the throne he still owed £1,000 to our Richard. The newly crowned Henry IV agreed that Richard should be repaid this amount. Richard’s career, now a very wealthy man, had evolved into that of a successful money lender particularly to kings and those of the nobility including Sir Simon Burley and John Beaufort, earl of Somerset. From 23 August 1388 to 23 July 1422, he made least 59 separate loans to the Crown of sums ranging from £4 to £2,833 (3).

About 1402 Richard made an advantageous marriage to Alice, daughter of Sir Ivo Fitzwaryn, a wealthy landowner who had no male heirs. This marriage thus brought with it the prospect of a generous inheritance. In 1402 Fitzwaryn actually settled properties in Somerset and Wiltshire upon his daughter and new son-in-law but Richard, ever preferring liquid capital to property, offered the titles to his brother-in-law, John Chideok, for the sum of £340 (4). However as things came to pass Alice predeceased both her father and husband. Sadly there would be no children from the marriage which seems to have been happy and when Alice fell mortally ill in 1409/10 Richard obtained a special licence from the king to bring a renowned Jewish doctor – Master Thomas Sampson from Mierbeawe – over from the continent to treat her. After Alice’s death Richard would remain a widower for the rest of his life.

Blue plaque outside 20 College Hill, EC4, the site of Richard Whittington’s London house. College Hill was first known c.1231 as Pasternosterchurchstreet commemorating the church that stood nearby but later shortened to Pasternosterstret by 1265 and then to ‘La Riole’ c.1303 after the foreign wine merchants to dwelt there named it after La Reole in Burgundy. It has also been known as Whytyngton Colledge.

Other than his London house he owned only a small handful of properties one of these being the manor of Over Lypiatt in Gloucestershire. This particular property however had belonged to Philip Maunsell, his maternal uncle up until 1395 when it was assigned in satisfaction for a debt of £500 to Richard Whittington, the celebrated mayor of London. This property Richard would eventually leave to his brother, Robert (5).

OFFICES HELD

Here are listed just some of the innumerous offices held by Whittington:

Common councillor, Coleman Street Ward 31 July 1384-86

Alderman of Broad Street Ward 12 March 1394- 24, June 1397. Lime Street Ward by 13 February 1398

Mayor of London 8 June 1397-13, October 1398, 13 October 1406-7 and 1419-20.

Sheriff, London and Middlesex, March 1393-4.

MP for the city of London 1416

Commissions to make arrests, London March, April, 1394, November 1407; of gaol delivery October 1397, June 1398; oyer and terminer Sept. 1401, March, April, October 1403, November 1405, May 1406, November, 1407, June, July 1409, May 1414, Feb. 1416, December 1417, November 1418.

To supervise the collection of Peter’s Pence in England August 1409; of inquiry, London January 1412 (liability for taxation), Dec. 1412 (seizure of merchandise), January 1414 (Lollards at large), July 1418 (possessions of Sir John Oldcastle).

Appointed to to administer revenues for building work at Westminster Abbey December 1413; recruit carpenters for the same March 1414.

Warden, Mercers’ Company 24 June 1395-6, 1401-2, 1408-9

Member of Henry IV’s council 1 Nov. 1399-18, July 1400.

Collector of the Wool Custom, London 6 Oct. 1401-5, November 1405, 20 February 1407-26, July 1410

Receiver General in England for Edward, earl of Rutland, by 7 May 1402

Mayor of the Staple of Westminster 3 July 1405. Calais by 25 Dec. 1406 – 14 July 1413 (6).

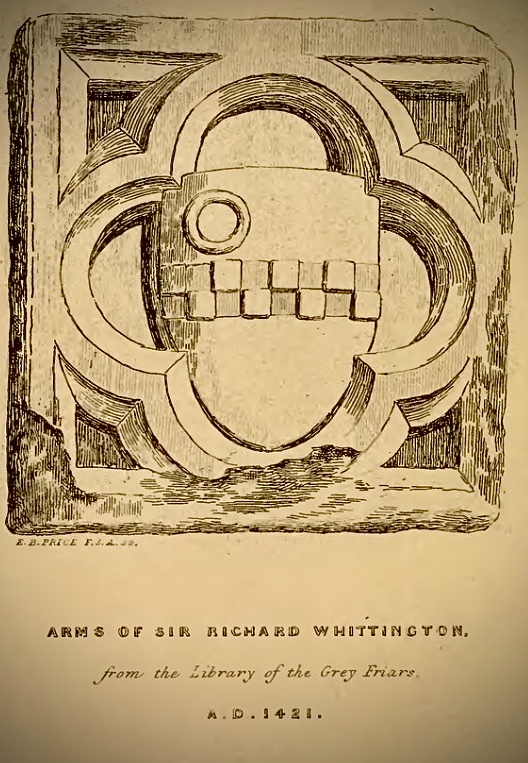

Arms of Richard Whittington. Drawing by E B Price.

CHARITABLE DEEDS

Ah! I hear you say, but were not works of charity considered de rigueur for the wealthy of those times? And yes although that is true Richard was always a generous benefactor, giving to numerous good causes throughout his life and prior to his death, and so much so that his reputation as such has come down to us through the centuries.

In 1401/02 he donated £6 13s 4d towards the building of a new nave at Westminster Abbey, perhaps because it was a project of his late patron, Richard II.

In 1409 he purchased the land close to his London home which lay next to his parish church and then acquired a licence to give it in mortmain to the rector, to allow the church to be rebuilt and a cemetery added. The task of rebuilding was completed by his executors.

In 1411 he contributed most of the funds for building and outfitting a library at Greyfriars including the amount of £400 for the books alone. The library at the Guildhall was also to benefit from his largesse.

He funded a refuge for ‘yong wemen that hadde done amysse in trust of good mendement’ i.e. unmarried mothers at St Thomas’ Hospital, Southwark (7).

He financed numerous new conduits and fountains giving Londoners access to clean water. These included the fountains in St Gile’s Courtyard and north of the church of St Botolph.

Other good works included the building of a public toilet known as Whittington’s Longhouse which had a total of 128 seats: 64 for men and 64 for women. This was built on a dock overlooking the Thames in Walbrook Street in the parish of St Martin Vintry. Survived until the Great Fire 1666 when it was rebuilt albeit on a more modest scale.

HIS WILL

When he drew up his will on the 5 September 1421, childless and a widower, he left all to charity other than the above mentioned manor of Over Lypiatt. The will which is long and very detailed can be found here for anyone who wishes to delve more deeply but here are just a few snippets:

I bequeath £100 to cover the costs of my funeral expenses and for saying vespers after my death, the Placebo and Dirige and on the following day a requiem mass; together with a monthly remembrance for my soul, the souls of my father, my mother, my wife Alice, and all those to whom I owe a debt of gratitude. I bequeath 1d. for every poor man, woman and child, to be distributed on the day of my funeral

I bequeath 40s. to be distributed, as my executors determine best, among poor people of the parish of St. Stephen Coleman Street, London

I bequeath 40s. to be distributed, as my executors determine best, among poor people of the parish of St. Michael Bassishaw, London. I bequeath 40s. towards the structural fabric of St. Alphege church, London, that they may pray for my soul and those of the aforementioned. I bequeath 20s. to be distributed, as my executors determine best, among poor people of that parish

£10 to be distributed, as my executors determine best, among poor people in the hospitals of St Mary without Bishopsgate, St Mary of Bethlem and St. Thomas in Southwark, and among the lepers of Lock, Hackney, and St Giles without Holborn. I bequeath 20s. to be distributed, as my executors determine best, among the poor brothers and sisters of the hospital of Elsing Spital.

For the repair and improvement of roads in bad condition, £100 to be distributed as my executors determine best, where the necessity is most felt.

I bequeath for distribution among those imprisoned in Newgate, Ludgate, Fleet, Marshalsea and the King’s Bench 40s. each week for as long as £500 holds out.

I leave to my executors named below the entire tenement in which I live in the parish of St. Michael Paternoster Royal, London, and all lands and tenements that I hold in the parish of St. Andrew, near Castle Baynard, London, and in the parish of St. Michael Bassishaw, as well as in the parish of St. Botolph outside Bishopsgate, in the same city; so that after my death they may sell them as soon as they may conveniently do so and distribute the proceeds for the good of my soul and the souls already mentioned….

I wish that my executors have in their custody a chest, secured with three locks, containing my goods and jewels, to be distributed for the good of my soul; and that none of those who are my executors remove anything from the same except in the presence or with the consent of all as a group. I further wish that my executors maintain and support my household together with meals for my personal servants for one year following my death, as they determine best (8).

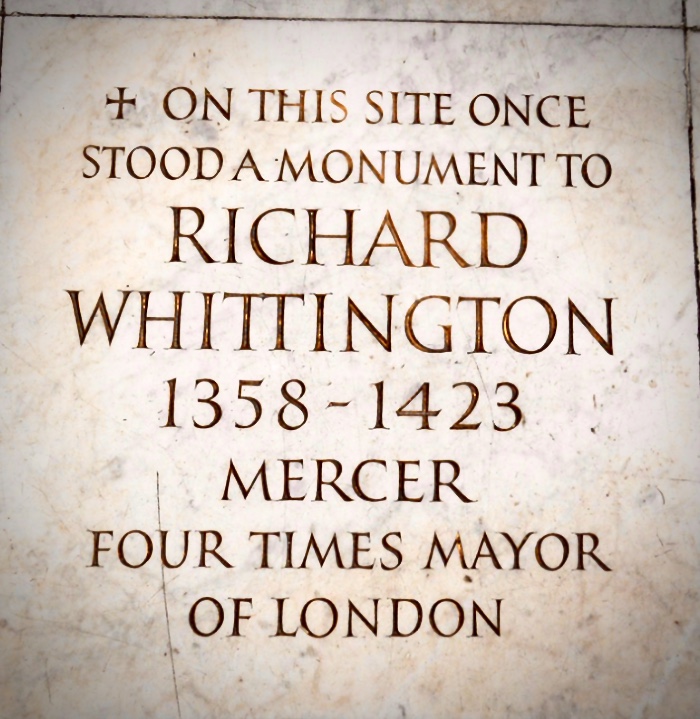

Upon his death in March 1423 Whittington was buried in the church he had rebuilt, St Michael Paternoster Royal, which stood on the corner of La Riole, now College Hill where his house once stood. This street before it was renamed La Riole was known as Paternosterstret because of the rosaries that were made there and later Whytyngton College In his will he had requested to be buried on the north side of the altar. He had rebuilt the church as a collegiate church, that is administered by a college of priests, known as Whittington College, hence the renaming of the lane to College Hill. This church was destroyed in the Great Fire of London but rebuilt. A stone now marks the site of Richard’s original burial site in the rebuilt church.

Stone marking the site of the burial place and monument of Richard Whittington in the now rebuilt St Michael Paternoster Royal. Photo stjamesgarlickhythe.org

A rather shocking postscript to this story is told by John Stow:

‘This Richard Whittington was in this church three times buried, first by his executors under a fair monument, then in the reign of Edward VI, the parson of the church, thinking some great riches, as he said, to be buried with him, caused his monument to be broken, his body to be spoiled of his leaden sheet, and again the second time to be buried, and in the reign of Queen Mary, the parishioners were forced to take him up to lap him in lead as afore, to bury him the third time and to replace his monument or the like over him again which remaineth and so he resteth’ (9).

It is one of the few times reading the usually very reliable Stow that I hoped he may have got it wrong so awful is it. I do hope the odious unnamed parson’s remains ended up on a dung heap where they belonged. But I digress and its best left unsaid what I would really like to say about this vile creature, whose name remains unknown, while our good Richard Whittington lives on after over 500 years. As Anne Sutton put it so succulently ‘What has survived, to be cherished and turned into a legend after his death, is the sense of civic and humanitarian duty which made him leave his personal fortune to the poor’. Bravo dear man…you did well.

View of St Michael’s seen from along College Street as it appears today. College Street, formerly Elbow/Eldebowe/Bow Lane should not to be confused with nearby College Hill where Richard Whittington’s house once stood (10). The medieval church was destroyed in the Great Fire of 1666 and rebuilt. This church was badly damaged when hit by a bomb in 1944 leaving only the walls and tower standing. As can be seen today these were incorporated when the church was rebuilt. Re-opened in 1968. Contains a large glass window commemorating Richard Whittington and his cat.

In 1436 a fine epitaph was penned for Whittington by the author of The Libelle of Englyshe Polyce :

‘And in worship nowe think I on the sonne Of marchaundy Richarde of Whitingdone, That loodes starre and chefe chosen floure. Whate hathe by hym oure England of honoure, And whate profite hathe bene of his richesse, And yet lasteth dayly in worthinesse, That penne and papere may not me suffice Him to describe, so high he was of prise, Above marchaundis to sett him one the beste! I can no more, but God have hym in reste’ (11).

One last thing. While it is true Richard Whittington, as far as we know, did not own a cat, it’s of course also perfectly possible that he did. After all, then as now, there is no better way to to get rid of mices and so forth. Therefore I would venture to say Richard Whittington did in fact own a cat although of course not the adventurous moggie portrayed in panto but no doubt an affectionate and companionable fellow. It therefore follows surely the Whittington family cat should have some sort of memorial too? Look no further than Westminster Abbey who erected a stained glass window to Whittington and his cat, depicted here as ginger, on the north side of the nave:

And here we have – drum roll – the most famous moggie of medieval times – Richard Whittington’s cat! Westminster abbey on the north side of the nave…

- Florilegium Urbanum Whittington’s Charity. Online article.

- Whittington, Richard (Dick) c.1450-1423. Oxford DNB. Anne F Sutton

- ‘Richard Whittington’, Studies in London Hist. ed. Hollaender and Kellaway. C M Barron. See also Historyofparliamentonline.org.

- Caroline Barron, “Richard Whittington: the man behind the myth”, Studies in London History ed. A.E.J. Hollaender and William Kellaway, London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1969

- BHO. A History of the County of Gloucestershire V II.

- .historyofparliamentonline.org.

- Stow p.274.

- Online article Florilegium Urbaniam – Religion -Whittington’s Charity.

- Stow p.216.

- A Dictionary of London p.164. Editor I. I. Greaves. London 1916.

- Libelle of Englyshe Polyce ed. Warner.

If you have enjoyed this post you might also like:

L’Erber – London Home to Warwick the Kingmaker and George Duke of Clarence

THOMAS CROMWELL’S HOUSE IN AUSTIN FRIARS

THE ORANGE AND LEMON CHURCHES OF OLD LONDON

GREENWICH PALACE – HUMPHREY DUKE OF GLOUCESTER’S PALACE OF PLEAZANCE

RICHARD WHITTINGTON He’s both my 18th and my 20th great uncle

LikeLike