A glimpse of St Martin’s church from the millpond looking north. This wonderful photo thanks to David Ireland.

‘It may not be liefull for euery man to vse his owne as hym lysteth, but eueyre man must vse that he hath to the most benefyte of his countrie. Ther must be somethynge deuysed to quenche this insatiable thirst of greedynes of men.…’ John Hales 1549.

Since early medieval times Britain’s landscape has been prolifically dotted with deserted villages. The abandonment of these villages was the result of, in the main, either pestilence, which led to the last few shell shocked survivors of these catastrophic events leaving their homes or because the landowners wanted to have the land for the more lucrative returns made from sheep farming. This view has been described as rather simplistic – Harriett Bradley argued in her interesting article that there were already changes afoot prior to the arrival of the Black Death in the 14th century – but agreed that the pestilence would have certainly accelerated matters (1).

Let’s look at the latter reason which brought about the forced abandonment of homes and villages by the people that had lived in them, some for generations. This particular type of eviction became known as the Enclosure Movement which, with all its resultant cruelty, led to an avalanche of evictions and was much denounced. Many worthies of the time railed against these evictions including John Rous, the 15th century Warwickshire chantry priest and antiquarian who also listed the 54 places “which, within a circuit of thirteen miles about Warwick had been wholly or partially depopulated before about 1486″ (2). Rous clearly did not believe in holding back and went full tonto with his description of Richard III comparing the late king to both the Antichrist and a scorpion, being born with a full set of teeth and hair flowing to his shoulders and who was excessively cruel in his days (3). He made verbal mincement of the unscrupulous landlords of the times and Matthew Green succinctly describes in his book “Shadowlands” how Rous castigated the landlords, describing them as worshippers of “Mammon”, “murderers of the impoverished“, “destroyers of humanity,” and “venomous snakes.” They had shown no mercy to “the children, tenants, and others whom they have forced from their homes by theft,” and so could expect “judgment without mercy” in the afterlife; furthermore he would certainly not be singing any masses for the souls of these “destroyers of towns‘ (4). An interesting excerpt from Green’s book can be found here.

Thomas More in his Utopia written in 1516 stated:

‘…those miserable people… are all forced to change their seats, not knowing whither to go; and they must sell, almost for nothing, their household stuff. When that little money is at an end, for it will soon be spent, what is left for them to do but either to steal and so to be hanged or to go about and beg’.

Decades later someone would write a short poem entitled ‘Stealing the Common from the Goose’ in the 18th century neatly encompassing the injustice of it all:

“The law locks up the man or woman

Who steals the goose from off the common,

But lets the greater felon loose

Who steals the common from the goose.”

During the excavations of 1964 the bones of a man who had laid down to die beside one of the houses was discovered. His name and story are unknown to us and we can only speculate. Was he, as Matthew Green suggests, ‘a famished vagabond’ at the end of his journey in this life or was he a villager, ‘obstinate to the end’, who returned home to die?

WHARRAM PERCY

Wharram Percy is one of the most well preserved examples of such a deserted village standing in an idyllic spot in the heart of the Yorkshire Wolds. This village, with the remains of its church, about 40 grassed over peasants houses plus two manor houses was indeed one of the victims of the Enclosure Movement although most probably already left vulnerable in the aftermath of the Black Death which had decimated the country in the 14th century leaving in its wake between a third and a half of the population dead. By 1349 Wharram Percy’s population of 67 was reduced to about 45. Basically this catastrophic pestilence would have a knock on effect bringing about radical change. The massively high death rate left behind fewer people to work the land. This, combined with some of the survivors having witnessed the agonising deaths of loved ones and friends abandoning their decimated villages in an effort to find an easier way of making a living, led to demands for higher wages from those who stayed. This turn of events would leave some smaller villages in a precarious position which would eventually sound their death knell. Wharram Percy would survive this calamity and a visitor in 1368 would have found ‘… about 30 of its houses still occupied, one of the mills was working profitably and both millponds generating an income from fishing. Though there were fewer households in the late 14th century, they were doubtless better off, as shown by the excavated large peasant longhouse overlooking the church.’ (5). Tragically the village would not survive Enclosure. The final eviction of four families and the demolition of their homes marked the end of village life in c.1500.

THE RESIDENTS

Now if you thought that you had drawn life’s short straw to be born into medieval peasant stock it could actually be even atrocious than first appears for there was several echelons of peasantry society. Those unfortunates who occupied the lowest rungs of the ladder were known as cottars. There was only one step lower you could go than a cottar and that was homeless beggar. These cottars, or cottagers as they were also known, could hold no land other than their toft which was a small yard or garden surrounding their home. Owning livestock or even a plough was out of the question. They would pay their rent to the lord of the manor via their labour. Any spare time they had was spent working as hired hands, if and when work became available, to augment their almost non existent wages. It’s believed that an area in the East Row at Wharram Percy was allocated to cotters homes due to the smaller size plots (6). Next step upwards on the ladder was the villeins also known as serfs. These villagers, as well as their toft, could hold an adjoining strip of land known as a croft which was larger than the toft and was used for keeping a few animals or growing crops as well as one or two oxgangs in the open fields (7).

Ploughing with oxen. Luttrell Psalter c.1335-1340. The British Library.

The villeins would also pay rent to the lord but in produce and cash as well as labour. The West and North Rows were probably where the homes and tofts of the villeins would have been situated. Villeins would have been unable to give up their homes or marry without the lord’s permission and their children would have been born into the same class. You had reached the upper echalons of the peasant class when you were a freeman. Freemen, also known as Sokemen, were less tied down by the obligations of the villeins and cotters. This freedom came at a price though because they would be less entitled to the lord’s protection if and when any problems arose – which no doubt they did. The larger longhouses situated on the West row were probably the homes of the Freemen/Sokemen. It’s sobering to think about the harsh lives, the sheer grinding poverty, that some of these unfortunate souls experienced especially the cottars. Let’s hope that the people in the big house fulfilled their noblesse oblige and gave a helping hand in hard times. However when life had taken its toll and you finally succumbed, worn out to the very bones, you did not have to go far for burial – Wharram Percy had its own fine church…

ST MARTIN’S CHURCH

Window from St Martin’s Church with two stone heads either side. These may represent two members of the Percy family. Photo thanks to Allan Harris @ Flikr.

St Martin’s begun life as a small and simple 10th century timber chapel the postholes of which were discovered during the excavations of the church in 1962-74. The rebuilding of the church in stone shortly before the Conquest in 1066 may possibly have been the work of a group of freemen/free peasants whose graves may be among those that lay in a distinct group and were covered by the ancient lids of Roman coffins. The names of some of these men have come down to us via the Doomsday Book of 1086 – Lagmann, Carli and Ketilbjorn.

Over the centuries the church was both enlarged and reduced in size depending on the size of the fluctuating population of the time. Following the last villagers being driven out c.1500 the church gradually fell into disrepair, with a series of complaints made about the condition of the chancel from 1555 onwards. As St Martin’s was the mother church of a parish serving four villages services still took place there. However by the 17th century three of these villages had also became deserted with just Thixendale surviving although a new vicarage was built in the early 18th century. Be that as it may, to save a five mile round trip Thixendale constructed its own church in 1870, which led to most of the remaining parishioners deserting St Martin’s. Services were still carried out though including burials which ceased in 1906, the last marriage in 1928 and the last service held in 1949 after which the fittings were removed (8). St Martin’s still stands, defiant albeit rather battered, minus its roof and half its tower gone following its collapse after a storm in December 1959.

Medieval font from St Martin’s church photographed c.1950s . historicengland.org.com

St Martin’s Church photographed c.1950 before the collapse of the tower and removal of roof. historicengland.org.uk

St Martin’s Church photographed c.1950 before the collapse of the tower and removal of roof. historicengland.org.uk

THE BURIALS

During the excavations of the church the northern side of the graveyard was excavated during which a total of 687 burials were excavated. These were estimated to be about 10% of the burials in the churchyard – 15% of which were of children who had died before their first birthday. This figure was much lower than the higher rate of infants deaths to be found in towns. It’s thought this may have been because Wharram Percy mothers breast fed their infants longer perhaps until they were about 18 months old. It was the weaning of infants that would herald in some of the awful conditions associated with malnutrition such as rickets etc., Malnutrition was not the only enemy – the remains of one small boy aged about 10 showed that he had suffered and died from leprosy. On a more positive note 40% of the burials were of individuals who had died aged over 50 with males outnumbering females by 3-2. Some of these adults had suffered from quite serious disabilities from birth but had made it to a reasonable age demonstrating that they must have been well cared for in the community. Poignantly one young woman, heavily pregnant, had succumbed to tuberculosis and an attempt had been made to save the unborn baby’s life by performing a caesarean. Sadly this had failed and the baby was buried lying between its mother’s thighs but it does demonstrate that even amongst peasant society who had so very little, life, including that of the smallest of infants, was highly valued. Dr Simon Mays, skeletal biologist at English Heritage’s Centre for Archaeology has said:

“We tend to think medieval people somehow got used to death because life could be so nasty, brutish and short. But this burial tends to rebut this and suggests life was every bit as precious, leading to drastic acts to preserve it‘ (9).

Aerial view from the north looking south. St Martin’s is the last building at top right hand side just below the millpond. Photo © Historic England

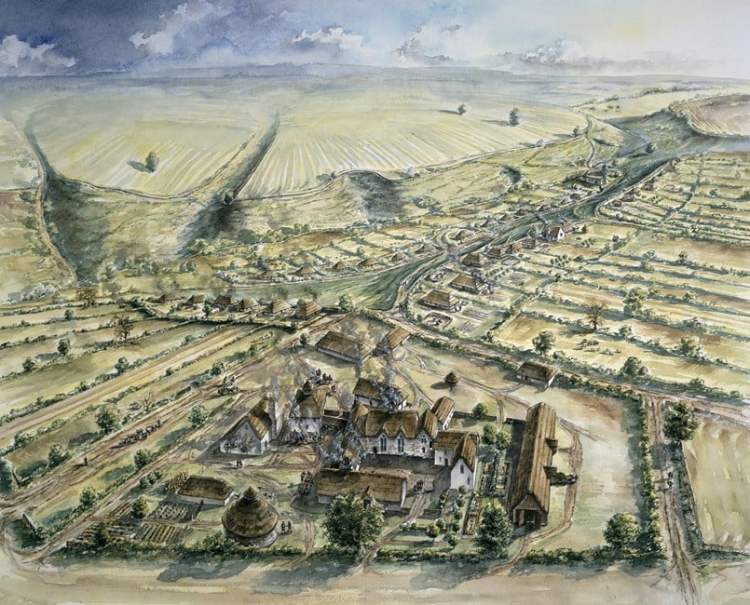

Reconstruction drawing of Wharram Percy of the same view showing the North Manor at the bottom with the peasant houses, tofts and crofts as they would have appeared in the late 12th century. Note the dovecot. The church can be seen in the distance at top right hand corner of the image. By Peter Dunn © Historic England

THE NORTH MANOR AND THE PERCYS

The manor was the largest and most important residential building in Wharram Percy and would have been home to several generations of the Percy family. Standing in the centre of a walled compound the residents would have enjoyed a higher rate of of privacy than elsewhere in the village. Following the Conquest in 1066 William the Conqueror had set out to dominate the northern parts of the country in a campaign that became known as the Harrying of the North. The effect this would have on Wharram Percy, or Warron as it was then known, was that two main landowners in the village, Lagmann and Carli (who may have been responsible for rebuilding the church (see above) lost their holdings which were granted to the Norman Sheriff of York and those of a third, Ketilbjorn, were granted to a Norman baron by the name of William de Percy. Thus the Percys had arrived in Warron which thereafter became known as Wharram Percy. Some of this William de Percy’s descendants would fare extremely well and would go on to later become members of one of the greatest families in northern England, the Northumberland Percys, building castles such as Alnwick and Warksworth. Their stories can be found easily elsewhere and no need to go into them here. The Wharram Percy branch of the Percys would leave the South Manor and move into the newly built North Manor which also benefitted from the addition of a small hunting park. It was around this time c.1254-1315 that the village enjoyed its golden era and the North and East Rows were built increasing the number of properties to about 40. However nothing lasts forever and around 1315 things took a bit of a nose dive when Peter, the heir of the resident lord of the manor, Robert Percy, died aged 25 without an heir. His wife was left bringing up two small daughters, Eustachia and Joan. Robert himself died in 1321, aged 76 followed shortly after by his second son Henry. This lack of a suitable heir was troubling enough for the villagers but then 1322 brought more bad news in the form of Scottish raids. There then followed an economic downturn with two-thirds of the village’s land uncultivated, plots unoccupied and the village’s two water mills disused. In an attempt to restore stability Eustachia was then married aged 14 to Walter Heslerton from a nearby village of that name. Four years later, on 1331, she gave birth to a son named Walter after his father. Walter Snr died in 1349, a victim of the Black Death. Walter Jnr was still a minor and therefore could not inherit the Wharram Percy estate. It was claimed by royal officials that Eustachia was mentally deficient and should come under the protection of the king allowing the crown to manipulate the management of her Wharram Percy estate for its own profit. In 1366 Eustachia died and her son Walter Jnr only outlived his mother by a year. On his death in 1367 the estate reverted to a distant relative, Henry, one of the more illustrious Percys of Spofforth Castle. Some time between 1394 and 1402 the Spofforth Percys would exchange Wharram Percy with Shilbottle, a manor owned by the Hilton family (10). The Hiltons seem to have been on the whole absent landlords. The ending for Wharram Percy was hoving into sight. It was a member of the Hilton family, William, Baron Hilton, who instigated the removal of the last four families and the demolition of their homes between the years 1488-1500. In the fullness of time the remains of the peasants homes would collapse in on themselves and both these and the streets, alleys and tracks they had known so well would become covered with a protective carpet of turf formed by the sheep pastures leaving behind the mounds and hollows that can be seen today, a sad indictment of when avarice overcomes good lordship. We shall leave the last sad word to Bishop Hugh Latimer who wrote on the 8 March 1549:

‘for where as have been a great many householders and inhabitants, there is now but a shepherd and his dog’

Stone head of lady in 14th century headdress in a window of the church. May represent one of the Percy ladies. Photo Ally Shaw Flickr.

Stone head of lady in 14th century headdress in a window of the church. May represent one of the Percy ladies. Photo Ally Shaw Flickr.

NOTE: For those unable to visit Wharram Percy for various reasons such as distance, lack of time or dodgy knees etc., I can thoroughly recommend the English Heritage Wharram Percy guide book. English Heritage have a large range of guide books covering the wonderful places under their management and care which which have been written by experts, are concise, affordable, beautifully illustrated and contain a wealth of information. Available from their online shop.

1. The Enclosures in England an Economic Reconstruction Harriet Bradley 1914.

2. Historia regum Angliae (History of the Kings of England). John Rous. Published around 1459-86.

3. Ibid.

4. Shadowlands: A Journey Through Lost Britain p.p.143.144

5. Wharram Percy Deserted Medieval Village p.8. Alastair Oswald former Senior Archaeologist Investigator at English Heritage.

6. Wharram Percy Deserted Medieval Village Alastair Oswald former Senior Archaeologist Investigator at English Heritage.

7.An oxgang was the amount of land tillable by one ox in a ploughing season. This could vary from village to village, but was typically around 15 acre. Wikipedia.org.

8. Heritagegate Historic England Research Records. Available online.

9. BBC News Channel interview with Dr Simon Mays Thursday 25 August 2005.

10. Wharram Percy Deserted Medieval Village p.20. Alastair Oswald former Senior Archaeologist Investigator at English Heritage.

If you have liked this you may also like:

A COLLECTION OF REVOLTING REMEDIES FROM THE MIDDLE AGES

THE MEDIEVAL PRIORY AND HOSPITAL OF ST MARY SPITAL

THE MEDIEVAL BED – A PRIZED POSSESSION

CLATTERN BRIDGE -A MEDIEVAL BRIDGE – KINGSTON UPON THAMES

Murder and mayhem in medieval London

THE MEDIEVAL DOGGIE AND EVERYTHING YOU EVER WANTED TO KNOW ABOUT THEM

3 thoughts on “WHARRAM PERCY – A DESERTED MEDIEVAL VILLAGE – VICTIM OF THE ‘ENCLOSURES’”