St Erasmus in Bishops Islip’s Chapel, Westminster Abbey by Joseph Mallord William Turner c.1796. The original chapel of St Erasmus, built by Elizabeth Wydeville, was the site of Anne Mowbray’s first burial and after the discovery of her lost coffin in 1964 she would be reburied in the rebuilt Chapel.

Anne Mowbray, Duchess of Norfolk, was born at Framlingham Castle, Suffolk, on Thursday 10 December 1472. John Paston wrote ‘On Thursday by 10 of the clock before noon my young lady was christened and named Anne‘ (1). Anne would die just eight years later at Greenwich Palace on or about the 19 November 1481, a few weeks short of her ninth birthday. Greenwich Palace has been said to be have been the favourite property of her mother-in-law, Queen Elizabeth Wydeville, as well as, presumably, a royal nursery as only six months after Anne’s death another royal child would die there – this time her sister-in-law, the fourteen year old Princess Mary. Anne was the sole heiress of John de Mowbray, Duke of Norfolk (b.1444) who had died suddenly on the 14 January 1476 when Anne was three years old. This left her as one of the most sought after heiresses of the time and only ten days after the death of her father ‘it was known that Edward IV was seeking her as a bride for his younger son, Richard of Shrewsbury, Duke of York‘(2). Agreement was eventually reached between Edward and Anne’s mother, Elizabeth Mowbray nee Talbot, the Duchess of Norfolk, with the Duchess agreeing ‘to forego a great part of her jointure and dower lands in favour of her daughter and little son-in-law, Richard, Duke of York. This act settled also settled the Norfolk lands and titles on the Duke of York and his heirs should Anne Mowbray predecease him leaving no heirs‘ which is precisely what transpired (3). Nothing has survived of Elizabeth Mowbray’s personal thoughts on this. The children were eventually married on the 15 January 1478 in St Stephen’s Chapel, Westminster, with the bridegroom’s uncle, Richard, duke of Gloucester, later Richard III, leading her by the hand into the chapel. Anne is perhaps best known for being the child bride of one of the ‘princes’ in the Tower.

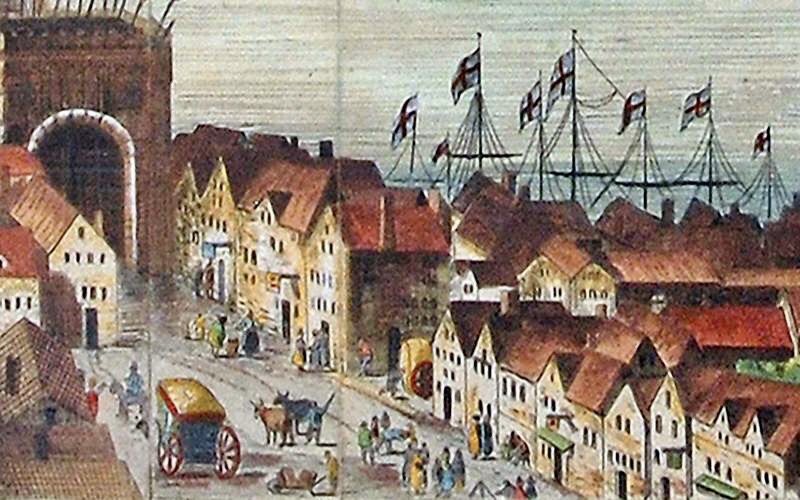

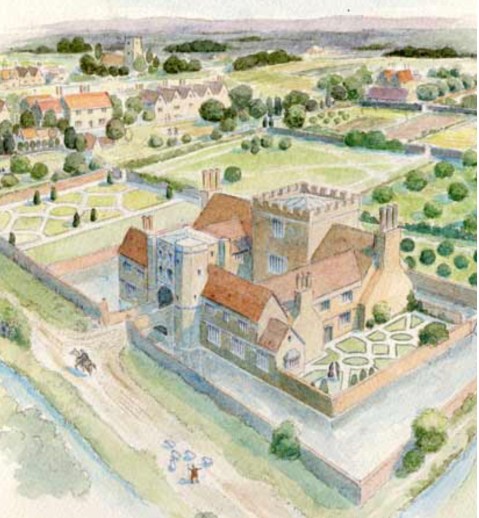

Framlingham Castle, Suffolk. Home to the Mowbrays and where Anne Mowbray was born Thursday 10 December 1472.

Following her death her father-in-law sent three barges to escort her body back to Westminster, where she lay in state in the Jerusalem Chamber before being buried in the Chapel of St Erasmus in Westminster Abbey which had been recently built by Elizabeth Wydeville, the funeral costs amounting to £215.16s.10d. This chapel was pulled down in 1502 to make way for a new grandiose Lady Chapel built by Henry VII. When the chapel was demolished Anne’s coffin was removed to the Abbey of the Minoresses of St Clare without Aldgate, also known as The Minories, where her mother, Elizabeth Mowbray – in the interim – had retired to. As her name was not listed among the burials at the Minories it was mistakenly believed that Anne had been reburied, along with others, in the new chapel dedicated to St Erasmus by Abbot Islip. Pleasingly the Abbot had managed to rescue the Tabernacle from the old chapel before its destruction and set it up in the new chapel, which is now known as the Chapel of our Lady of the Pew.

It’s intriguing to remember that Anne’s mother, Elizabeth Mowbray nee Talbot, dowager Duchess of Norfolk, was sister to none other than Lady Eleanor Butler/Boteler nee Talbot (c. 1436 – June 1468) believed to have been Edward’s first and lawful wife before his thus bigamous marriage to Elizabeth Wydville. See Titulus Regious. So ironically Anne’s aunt, the said Eleanor, was in fact her father-in-law’s true wife – the irony of which surely would not have been wasted on neither the king or Elizabeth Wydville unless they were both suffering from selective amnesia (4). Her mother’s privy thoughts on this scandalous situation, assuming Eleanor had told her of her secret marriage to Edward, are unrecorded as are her thoughts on the ‘unjust and unacceptable‘ division of the Mowbray inheritance (5). The explanation of this dishonourable treatment of the Mowbray inheritance is rather complex and I won’t go into it here suffice to say anyone interested in finding out more should read Anne Crawford’s article, The Mowbray Inheritance which covers the matter more than adequately (6).

Anne’s mother, Elizabeth Mowbray nee Talbot. Her portait from the donor windows in Holy Trinity Church, Long Melford, Suffolk.

Anne – the nature of her final illness eludes us – would no doubt have gently receded and become forgotten in the mists of time had not her coffin been discovered by workmen on the 11 December 1964 propelling her on to the front page of newspapers leading to a modern day representative of Anne, an outraged Lord Mowbray, protesting in the strongest possible terms about the treatment of her remains. This quickly led to the matter being swiftly resolved, and Anne’s remains, surrounded by white roses, were once again laid in state in the Jerusalem Chamber, as they had been 500 years previously. Anne was reburied in the Chapel of St Erasmus, with erroneous and histrionic reports stating that she had been interred ‘as near as possible’ to the remains of her young husband, Richard, whose purported remains lay in the infamous urn in the Henry VII Chapel. Later Lawrence Tanner, Keeper of the Muniments and Librarian of Westminster Abbey (and in a position to know) was to debunk this myth, writing that he, himself, had suggested that Anne’s remains be reinterred ‘very near to the probable site of her original burial place’ which was what duly happened (7).

Anne’s lead coffin with latin inscription, with her ‘masses of brown hair’. Photo from ‘London Bodies’ Compiled by Alex Warner. Museum of London publication.

Anne Mowbray’s hair. This is a true representation of the colour of Anne’s hair although it may have been a shade darker in her lifetime. Photo from ‘London Bodies’ Compiled by Alex Warner. Museum of London publication.

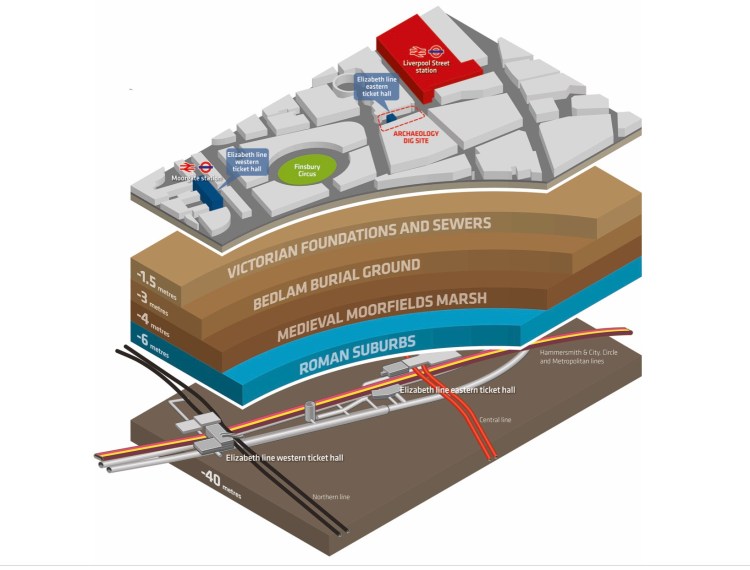

So what happened from the time of the discovery of Anne’s lead coffin to her reburial in the Abbey? The story is taken up by Bernard Barrell, a former member of the Metroplitan Police, who was an ‘unofficial police contact‘ whenever a coffin was unearthed in the area. According to Mr Barrell, in December 1964 workmen using a digging machine opened up a deep void in the ground revealing a brick vault filled with rubble, wherein they found a small lead coffin. After a police constable had been called to the scene the coffin was transferred to Leman Street Police Station. When Mr Barrel was called to the police station he was able to identify where the coffin had been discovered as the site of the Minories and was medieval in date. After satisfying the Coroner’s Office that the burial was indeed medieval and of archaeological interest he was instructed that if he was ‘unable to dispose of the coffin to a bona fide claimant‘ within 24 hours it would be buried in a common grave in the City of London Cemetery, Manor Park. In the nick of time Mr Barrell noticed a plate attached to the upper surface of the coffin which had now been damaged when removed from the ground and stood upright. On cleaning the plate with a wet cloth, Mr Barrell revealed a medieval ‘black letter’ text in Latin which was difficult to decipher however he could make out two words ‘Filia’ (daughter) and ‘Rex‘ (King) Realising this was no ordinary burial but that of someone of high status, a medieval latin scholar was located and hastily summoned to the station, and who then deciphered the whole text which read:

Hic iacet Anna ducissa Ebor’ filia et heres Johannis nuper Norff’ comitis Mareschalli Notyngham & Warenn’ ac Mareschalli Anglie ducis de Mowbray Segrave et Gower nuper uxor Ricardi ducis Ebor’ filii secundi illustrissimi principis Edwardi quarti regis Anglie et Francie et domini Hibernie que obiit apud Grenewych xix die Novembris anno domini MCCCCLXXXI et anno regni dicti domini reges xxi

Which translates into:

“Here lies Anne, Duchess of York, daughter and heiress of John,late Duke of Norfolk, Earl Marshal, Earl of Nottingham and Warenne, Marshal of England, Lord of Mowbray, Segrave and Gower. Late wife of Richard Duke of York, second son of the most illustrious Prince Edward the Fourth, King of England and France, and Lord of Ireland, who died at Greenwich on the 19th day of November in the year of Our Lord 1481 and the 21st year of the said Lord King

The coffin was then taken by police van to the Museum of London, where the remains were examined and the coffin conserved and repaired (8).

Lawrence Tanner then takes the story over.

‘I saw the body a few days after the coffin had been opened and a very distressing sight it was and again, after it had been cleaned and beautifully laid out in its lead coffin. She had masses of brown hair’. Tanner as already mentioned above, suggested that a grave be made as near as possible to where she had been previously buried. And ‘There on a summer evening, after having laid in state covered by the Abbey Pall in the Jerusalem Chamber, the body of the child duchess was laid to rest. It was a deeply moving and impressive little service in the presence of a representative of the Queen, Lady and Lord Mowbray, Segrave and Stourton (representing Anne’s family), the Home secretary, the Director of the London Museum and one or two others (9)

Anne’s lead coffin surrounded by white flowers and candles, lying in state in the Jerusalem Chamber, on the Westminster Pall.

And so, on the 31 May 1965, Anne was reburied in an honourable place, with tenderness, love and care. It has been speculated that her coffin had been taken to the Minories as a temporary measure and the intention was for her to be reburied when the new chapel at Westminster Abbey was completed. Maybe, however, I’m unconvinced. Unhelpfully her daughter’s reburial was never mentioned in Elizabeth Talbot’s will, despite her own request to be buried close to Anne Montgomery. I believe it’s likely that the widowed Dowager Duchess of Norfolk, then living in retirement at the Minories, requested that her little daughter be returned to her, with the intention that when her time came, they would be finally buried close together. The historian John Ashdown-Hill wrote that even though ‘the remains of Elizabeth Talbot, Duchess of Norfolk, must have been lying quite close to those of her daughter…they were apparently not noticed’ (10).

- Philomena Jones, Anne Mowbray, Richard lll Crown and People p.86

- Ibid p.86

- Ibid p.88

- R.H. Helmholz, ‘The sons of Edward IV: a canonical assessment of the claim that they were illegitimate’, in Richard III: Loyalty, Lordship and Law, ed P.W. Hammond

- Anne Crawford The Mowbray Inheritance, Richard lll Crown and people p.81

- ibid p.81

- Lawrence Tanner, Recollections of a Westminster Antiquary p192

- Charles W Spurgeon The Poetry of Westminster Abbey p.207, 208, 209

- Lawrence Tanner, Recollections of a Westminster Antiquary, p192.

- John Ashdown-Hill The Secret Queen Eleanor Talbot The Woman Who Put Richard lll on the Throne p.248

If you enjoyed this post you might also like

Those mysterious childrens coffins in Edward IV’s vault….

EDWARD OF MIDDLEHAM ‘SON TO KYNG RICHARD’ & THE MYSTERIOUS SHERIFF HUTTON MONUMENT

MARY PLANTAGENET – DAUGHTER OF EDWARD IV & ELIZABETH WYDEVILLE – A LIFE CUT SHORT

A Portrait of Edward V and Perhaps Even a Resting Place?- St Matthew’s Church Coldridge

Grave Marker for Mary Godfree, a victim of the Great Plague who died 2 September 1665.

Grave Marker for Mary Godfree, a victim of the Great Plague who died 2 September 1665. TWO MEN IN THEIR 40S BURIED HOLDING HANDS FROM ONE OF THE LAYERS OF THE CHARTERHOUSE BURIAL SITE.

TWO MEN IN THEIR 40S BURIED HOLDING HANDS FROM ONE OF THE LAYERS OF THE CHARTERHOUSE BURIAL SITE.

Wooden ball used for playing bowls

Wooden ball used for playing bowls