COWGATE NORWICH, DAVID HODGSON c.1860. WHITEFRIARS STOOD ON THE EASTERN SIDE BETWEEN THE CHURCH OF ST JAMES POCKTHORPE (SEEN ABOVE) AND THE RIVER A SHORT DISTANCE AWAY..NORWICH MUSEUM

On 30 June 1468, died Lady Eleanor Butler née Talbot. Eleanor came from an illustrious family. Her father was the great John Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury, her mother Margaret Beauchamp’s father was Richard Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick. Richard Neville Earl of Warwick, later known as ‘The Kingmaker’, was her uncle by marriage. Eleanor’s sister, Elizabeth, was to become the Duchess of Norfolk and the mother of Anne Mowbray, child bride to Richard of Shrewsbury, duke of York. Eleanor was a childless widow, her husband, Sir Thomas Butler, heir to Ralph Butler, Lord Sudeley, having died around 1459 possibly of injuries sustained at the battle of Blore Heath (1)

It would seem that the young widow caught the eye of the even younger warrior king Edward IV, who fresh from leading the Yorkists to victory at Towton and the overthrow of Henry VI, found himself swiftly propelled onto the throne of England. No doubt he was giddy with success because quite soon after having met Eleanor he married her in secret, an amazingly stupid action, and one which would come back to haunt him, as well as his bigamous wife Elizabeth Wydville, with all the subsequent and tragic repercussions for his family. See Titulus Regius for more information. The relationship between Edward and Eleanor was doomed to be one of short duration, the reasons for this being lost in time. Much has been written on this subject and I would like to focus here on the Carmelite Friary known as Whitefriars, Norwich, where Eleanor was later to be buried.

Whitefriars had been founded in 1256 by Philip de Cowgate, son of Warin, a Norwich merchant who settled lands there upon William de Calthorpe ‘upon condition that the brethren of Mount Carmel should enter and dwell there without any molestation for ever and serve God therein‘. Sadly much later Henry VIII was to have other ideas. However returning to Philip de Cowgate. Following the death of his wife, the ageing Philip ‘took upon him the Carmelite habit and entered the house of his own foundation‘ dying there in 1283. The building of Whitefriars was completed about 1382 and so begun its long and interesting journey through history. The notable persons being buried there are too numerous to mention as are the many benefactors but the various highs and lows make interesting reading. Notable incidents include:

1272, 29 June: ‘On the feast of St Peter and Paul in the early morning when the monks rise to say the first psalms, there was an earthquake. The tower of Trinity church fell….’

Further problems for the friary occurred later on that year –

1272, 11 August ‘….the citizens of the city attacked the monastery and burnt a large part of the building’

1450 John Kenninghale built a ‘spacious new library’

1452 A group of people begun to cause disturbances in the neighbourhood:

‘Item xl of the same felechep came rydyng to Norwich jakked and salettyd with bowys and arwys, byllys, gleves , un Maundy Thursday, and that day aftyr none when service was doo, they, in like wise arrayid, wold have brake up the Whyte Freris dores, where seying that they came to here evensong, howbeit, they made her avant in town they shuld have sum men owt of town’. However ’the Mayer and alderman with gret multitude of peple assembled and thereupon the seyd felischep departid’. (Paston Letters, ii, 268)

“Item, xlti of the sayd riottys feloshippe, be the comaundement of the same Robert Lethum, jakket and saletted, with bowes and arowys, billys, and gleyves, oppon Mauyndy Thursday, atte iiij. of the clokke atte after nonne, the same yere, comyn to the White Freres in Norwyche, and wold have brokyn theyr yates and dorys, feynyng thaym that they wold hire thayre evesong. Where they ware aunswered suche service was non used to be there, nor withyn the sayd citee atte that tyme of the daye, and prayd them to departe; and they aunswered and sayd that affore thayre departyng they wold have somme persons ouute of that place, qwykke or dede, insomuch the sayd freris were fayn to kype thaire place with forsse. And the mayr and the sheriffe of the sayd cite were fayn to arere a power to resyst the sayd riotts, which to hem on that holy tyme was tediose and heynous, consedryng the losse and lettyng of the holy service of that holy nyght. And theroppon the sayd ryoters departid.” (Paston Letters, ii, 309-310)

1468, July – Lady Eleanor Butler, née Talbot, daughter of the Earl of Shrewsbury and sister to the Duchess of Norfolk, born c.1436 died 30 June 1468 was buried in the friary.

1479 – ‘The great pestelence in Norwich’

1480 – ‘The great earthquake upon St Thomas nyght in the moneth of July’ Calendar of Charters and Rolls preserved in the Bodleian Library, ed. William H. Turner, (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1878)

1485 – King Richard III confirmed all the houses, lands and privileges of the Carmelites. Could this be connected to the burial of Eleanor – his sister in law – in that place?

1488/9 – ‘In the langable rental of the fourth of Henry the seventh, these friars are charged two-pence half-penny for divers tenements which they had purchased’.

1538, 2I September – The duke of Norfolk wrote to Thomas Cromwell ‘intended yesterday to have ridden to Norwich to take surrender of the Grey Friars, but was ill and so sent his son of Surrey and others of his council who have taken the surrender and left the Dukes servants in charge. Thinks the other two friars should be enjoined to make no more waste. The Black Friars have sold their greatest bell’.

1538 September – ‘The house of friars (Whitefriars) have no substance of lead save only some of them have small gutters’

1538 7 October – Letter from the Duke of Norfolk to Thomas Cromwell – ‘The White and Black Friars of Norwich presented a bill, enclosed, for Norfolk to take the surrender of their houses, saying the alms of the country was so little they could no longer live. Promised ‘by this day sevennight’ to let them know the kings pleasure: begs to know what to do and what to give them. They are very poor wretches and he gave the worst of the Grey Friars 20s for a raiment, it was a pity these should have less’(2)

The Friary was finally dissolved in 1542 and its lease granted to Richard Andrews and Leonard Chamberlain. Shortly after which the land was then divided into many different ownerships. The rest is history….

But back to the present – in 1904 foundations were discovered and in 1920 six pieces of window tracery were found and built into a wall at Factory Yard. These unfortunately were cleared away and lost when Jarrolds, the printers, extended their works. Thanks to the intrepid George Plunkett who took photographs of old Norwich between 1930- 2006 we can see this tracery before it disappeared forever.![Whitefriars Cowgate Factory Yard tracery [1651] 1937-05-29.jpg](https://murreyandblue.files.wordpress.com/2018/06/whitefriars-cowgate-factory-yard-tracery-1651-1937-05-29.jpg?w=624&h=415) Whitefriars Cowgate Factory Yard tracery. Photographed in 1937 by George Plunkett.

Whitefriars Cowgate Factory Yard tracery. Photographed in 1937 by George Plunkett.

Mr Plunkett also took photos of the now famous Gothic arch as it was in 1961 after it had recently been opened out. Sadly he reported that ‘a dilapidated flint wall adjoining the bridge was taken down as not worth preserving – a modern tablet identified it as having once belonged to the anchorage attached to the friary’ (3).![Whitefriars Cowgate flint wall [3187] 1939-07-30.jpg](https://murreyandblue.files.wordpress.com/2018/06/whitefriars-cowgate-flint-wall-3187-1939-07-30.jpg?w=631&h=419)

The flint wall before demolition – photograph by George Plunkett c1939![Whitefriars Cowgate friary doorway W side [4615] 1961-07-07.jpg](https://murreyandblue.files.wordpress.com/2018/06/whitefriars-cowgate-friary-doorway-w-side-4615-1961-07-07.jpg?w=610&h=401)

Whitefriars Cowgate friary doorway west side uncovered in 1961. Stood adjacent to the anchorage. Photograph by George Plunkett

![Whitefriars Cowgate friary doorway E side [6512] 1988-08-17.jpg](https://murreyandblue.files.wordpress.com/2018/06/whitefriars-cowgate-friary-doorway-e-side-6512-1988-08-17.jpg?w=605&h=440)

Whitefriars Cowgate friary doorway East side 1988. Photograph by George Plunkett.

Up to date views of the friary doorway. With many thanks to Dave Barlow for permission to use his beautiful photos….

All that remains above ground on the site of the the once magnificent Whitefriars – photos courtesy of Dave Barlow

However….

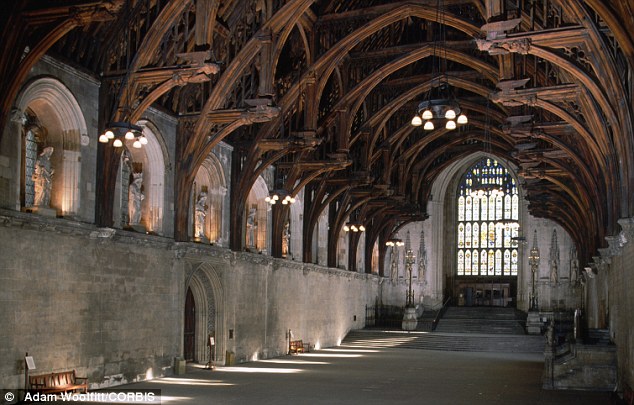

THE ARMINGHALL ARCH

An important Whitefriars relic, no longer in its original position, survived and went on to become known as the Arminghall Arch. This 14th century arch has experienced a number of moves since it was taken down during the Dissolution. It was first of all erected at Arminghall Old Hall. There it remained until the Hall was also demolished. It was then acquired by Russell Colman who transferred it to his grounds at Crown Point. From there it has now finally been installed at Norwich Magistrates Court, just across the bridge from its original position. It was through this arch that the funeral cortege of Lady Eleanor would have passed in 1468.

‘ARMINGHALL OLD ARCH’ 14th century arch removed from Whitefriars at the time of the Dissolution. Now in Norwich Magistrates Court.

Such is progress……

For those who wish to delver further into Lady Eleanor’s story the late John Ashdown-Hill’s Eleanor the Secret Queen – the Woman who put Richard III on the Throne is recommended.

l) The Secret Queen, Eleanor Talbot p74 John Ashdown Hill

2) The Medieval Carmelite Priory at Norwich, A Chronology Richard Copsey, O. Carm.

3) George Plunkett’s website, particularly this map.

![Whitefriars Cowgate Factory Yard tracery [1651] 1937-05-29.jpg](https://murreyandblue.files.wordpress.com/2018/06/whitefriars-cowgate-factory-yard-tracery-1651-1937-05-29.jpg?w=624&h=415)

![Whitefriars Cowgate flint wall [3187] 1939-07-30.jpg](https://murreyandblue.files.wordpress.com/2018/06/whitefriars-cowgate-flint-wall-3187-1939-07-30.jpg?w=631&h=419)

![Whitefriars Cowgate friary doorway W side [4615] 1961-07-07.jpg](https://murreyandblue.files.wordpress.com/2018/06/whitefriars-cowgate-friary-doorway-w-side-4615-1961-07-07.jpg?w=610&h=401)

![Whitefriars Cowgate friary doorway E side [6512] 1988-08-17.jpg](https://murreyandblue.files.wordpress.com/2018/06/whitefriars-cowgate-friary-doorway-e-side-6512-1988-08-17.jpg?w=605&h=440)