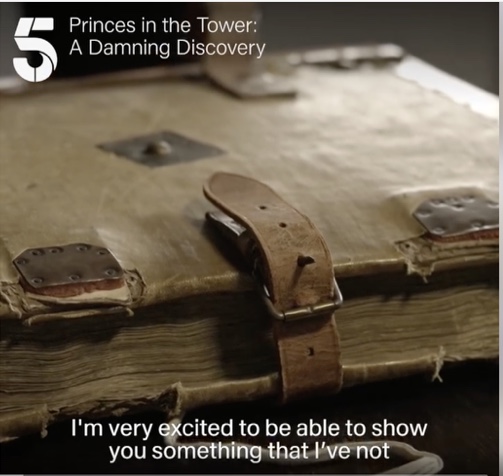

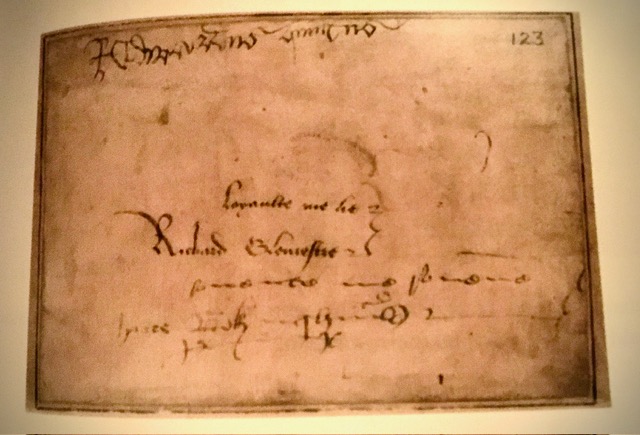

Titulus Regius. Now in the National Archives. Photo thanks to thehistoryofengand.co.uk

Titulus Regius was the Act of Succession that confirmed Richard III’s title to the throne. With many thanks to Annette Carson for this following guest post which explains in great depth why Henry VII’s repeal of the Act did not have the effects generally assumed. Annette was a member of the Looking for Richard Project that found the king’s grave and has written a number of books on Ricardian subjects including the excellent Richard III: The Maligned King, Richard Duke of Gloucester as Lord Protector and High Constable of England, Richard III: A Small Guide to the Great Debate and a new translation of Domenico Mancini: de occupatione regni Anglie with copious notes.

***************

For several years now I have found myself raising a sceptical eyebrow at the generally repeated assertion that Henry VII’s repeal of Titulus Regius in 1486 ‘automatically legitimized’ (or worse, ‘re-legitimized’) [1] Elizabeth of York, her brother Edward V and the other offspring of Edward IV. [2]

From what I knew of the common law in England, it had no provision to de-bastardize offspring that were adjudged as born of adultery or other illicit liaisons. The Church, desiring to hold fast to its control, had reason to incentivize marital transgressors to return to the fold, so canon law sometimes afforded ways in which their children could be made retrospectively legitimate. But any such decision of the Church was no automatic passport to override the common law, which jealously guarded its sole jurisdiction over inheritance rights. ‘Automatic’ was not a concept that would apply where bastardy was concerned.

I was particularly uncomfortable with the idea that, if the bastardy was somehow revoked, then by the same token the lawful election, coronation and reign of King Richard III was equally revoked. After all, the words titulus regius indicate that the purpose of the Act of Succession of 1484 was to confirm and ratify Richard’s royal title.[3]

However, seeing that my research energies were concentrated, as ever, on Richard III himself, I left these ideas untested. But I have always had a firm view on that other debatable matter of ‘de-bastardization’, King Richard II’s 1397 Act of Legitimation for the Beaufort clan. We are on safer ground with terminology here, as ‘legitimation’ has a specific legal meaning: rendering legitimate by decree or enactment, i.e. by means of an instrument that sets out its intentions in writing. Unlike Henry VII, at least with Richard II’s de-bastardizing you know where you are (though many writers of history have got it wrong – see later).[4]

To return to the repeal question, my aim here is to examine what was the result in law of Henry VII’s repeal process, and whether it had any effect in practice on the matter of the bastardy. I have now given this a fair amount of time and formulated a counter-argument to the general assumption of the repeal’s effect, based on what I believe to be recorded facts and established legal precepts. As ever, with new research comes the unwelcome situation that one would wish to have done it before publishing a book like Richard III: The Maligned King, but I hope to incorporate this into future editions.

I should here recapitulate how the bastardy of Elizabeth and her siblings came about. In summary, Edward IV had secretly wed Lady Eleanor Talbot, daughter of the renowned Earl of Shrewsbury, a few years before he secretly took to wife Elizabeth Woodville in 1464. And Eleanor had been living at the time of the king’s second marriage … which, being bigamous (as well as clandestine), was never a legal marriage and hence their children were illegitimate. And Edward had died without taking steps to regularize the situation. The government of the realm in June 1483 was faced with verifying this web of secret relationships and determining whether Edward’s heirs, being illegitimate, could succeed to the throne. Their verdict was that bastardy barred them from inheritance, and Richard Duke of Gloucester was duly petitioned to take the crown as Richard III. These circumstances were rehearsed, reaffirmed and ratified in January 1484 in Titulus Regius.

As I see it, Henry VII’s action of repeal was similar to other stratagems by that king and his government when they collaborated in fudging an inconvenient issue, so that an impression was created which they then cultivated as fact.[5] In this case the king’s inconvenient issue was that he was a virtual unknown who had lived abroad for the past 14 years and whose army had unexpectedly won a battle. He could command little unreserved support as an individual, but could cultivate a wider support base, bringing in Yorkists, if he committed to marrying Elizabeth, eldest daughter of the house of York.

There is much that I must leave out in order to concentrate on this single topic. So I will content myself by saying that Henry Tudor played to entrenched objections about the previous government’s decision to set aside Edward IV’s offspring from the succession. Whether their objections arose from loyalty or self-interest or plain ignorance of weighty matters of state, the men who held them looked to have that hated decision of 1483 overturned by Henry Tudor. His chosen method of repealing the Act unread appeased their sensibilities while avoiding actually reviewing the case and rebutting it.

I hardly need to emphasize that illegitimacy wasn’t a major social stigma among royalty and nobility, and of course a king could marry a bastard if he chose; indeed, Henry VII married Elizabeth of York five days before the repeal was enacted. So her bastardy as a bride was not a barrier. In England, the primary consequence of illegitimate birth was, put simply, the inability to inherit lands or titles. Henry Tudor had already disinherited her upon his winner-takes-all seizure of England together with Elizabeth as his wife. Nor had her illegitimacy diminished the royal status and courtesies she continued to enjoy after 1483.[6]

This should adequately dispose of the idea that Henry Tudor ‘couldn’t marry Elizabeth unless he rendered her legitimate’; nevertheless he was certainly invested in bolstering his weak claim to be a royal prince by marrying a royal princess. It will be recalled that owing to this very weakness, to get support for his royal pretensions in 1483 from the pro-Edward V rebels in Brittany, he had promised them he would marry Edward IV’s daughter. In fact, in 1484 he even had the presumption to obtain a papal dispensation for that marriage! Both these moves were undertaken after she had already been judged illegitimate. However, although he was invested in marrying her regardless, the one thing he couldn’t ignore was the constituency who had rebelled against the disinheriting and deposition of Edward V on grounds of bastardy: they demanded something be done about it. And they very probably included his bride’s mother. As he made clear to his justices in 1486 (see Appendix), it was the Act ‘that declared bastards the children of Edward IV’ that he needed to repeal. Of course the justices well knew, as did the Lords Spiritual and Temporal who would be required to sanction the repeal, that the laws of the Church had bastardized them, not the laws of man. Which Henry VII’s legal advisers also knew perfectly well.

There must have been lengthy conferences lasting way into the night, chewing over legal processes. Obviously there was concern as to what the effect would be on Elizabeth’s siblings, particularly her disappeared brothers, the princes Edward V and Richard of York. I leave aside the view that they were long dead, which Henry Tudor showed no sign of believing, and which was certainly not held universally, as witness the healthy support gained by pretenders claiming their identities. Even had he and his advisers been so stupid as to bury their heads in the sand over the princes, there were other living siblings to remember, including several sisters with husbands and/or potential husbands, not forgetting their heirs.

There is little doubt in my mind that the new king’s advisers assured him repeal was the best course because it would be purely cosmetic, and that if anyone affected should claim they had been legally rendered legitimate, it would be a simple matter to disabuse them. At any rate he decided to go ahead, and his first step was to call together the justices of the Exchequer Chamber on 23 January, the first day of the Hilary Term and first day of Parliament.

The report in the Year Book[7] shows the tone of domination by Henry VII that was set for this meeting, which has been recorded in various printings and manuscripts since the 16th century, many having differences in wording. By comparing a selection of variants I have determined a reliable text taken from 1555 which is reproduced in my Appendix. The report opens, significantly, with the statement that the justices were ‘taking direction’ from the king (pristerount son direccion) [modern French grammar did not apply to Law French]. From this flowed subsequent comments, i.e. that the Act was too scandalous to be re-read, with the justices closing their eyes to all its contents save nine words quoted from the opening of the petition section (‘the bill’) for the purpose of identification.

They then assisted Henry VII in framing his decree of repeal to Parliament, including a prohibition against anyone else reading the Act. Every copy must be removed from the records and destroyed by fire, upon pain of imprisonment. This was a deliberately obfuscatory process for the justices to collude in; but they were evidently given no option to deliberate among themselves as the Act of Repeal was presented to Parliament straight after their session that very day.

The way Henry Tudor declared his will to his justices stated that the 1484 Act ‘qui bastard les enfants’, was to be repealed. The fact that its original enactment had been to ratify Richard’s title as King of England was not even mentioned, which confirms that his key priority was to shut down the bastardy problem: the only references to Richard III in the repeal were to identify the Act and its date. Since Tudor and his lawyers were probably the only people who had actually read the Act during the past two years, I would argue they knew Richard’s title was unassailable anyway. This was clearly behind the decree that it should not only be repealed but repealed unread by anyone.

As to his excuse that its contents were too scandalous, this was obviously a subterfuge: the Act contained over 2,000 words, yet the words referring to the bastardy amounted to just 202 (which historian Charles Ross went so far as to describe as ‘a kind of afterthought’!).[8] The king’s aim, of course, was a cover-up. Whatever debate was allowed would be confined to his magnanimous intentions towards Elizabeth of York. By preventing access to its contents he could lead his blindfolded Parliament to acquiesce in the fiction (a) that his purpose was simply to revoke the bastardy of his bride, and (b) that this was in fact achieved.

Henry VII’s actual achievement was merely to annul and remove the written parliamentary record that confirmed and reasserted the decisions taken by the government in June 1483. His process sidestepped having to apply any legal test to examine whether the grounds for those decisions were as scandalous as he alleged. I am sure he realized that, if tested, they would be upheld. This is evidenced by his reaction to the Lords in Parliament, reported in the Year Book, when some of them declared that the Bishop of Bath and Wells, Robert Stillington, was responsible for the Act and demanded he be brought in to answer for it. This the king immediately refused, saying he had pardoned the bishop and did not wish it (though some bishops in the chamber were against this decision).[9]

From this identification of Stillington, perhaps we can now put an end to further doubt that the bishop was the chief witness to testify to Edward IV’s secret first marriage: not only from the above evidence, but from the Crowland Chronicle, and in greater detail from the memoirs of Philippe de Commynes who asserted that Stillington had been present (he would have been a mere canon at the time). The arrest of Stillington was one of Henry Tudor’s first orders after Bosworth, and he hounded the terrified bishop the length of the country until he found and imprisoned him. The eventual pardon was issued on grounds of ill health, though it mentioned nothing of any involvement in the petition or the Act.

The governmental decisions of June 1483

We may be sure the evidence sworn by Bishop Stillington would have been tested thoroughly in June 1483 by the Council and the Three Estates (including the Lords Spiritual – the archbishops, bishops and other clergy) in whose hands lay the governance of the realm.

Although many historians with traditional views have reserved the right to disbelieve his testimony, it was never refuted at the time and nor has it been since. We may therefore reserve the right NOT to disbelieve it, unless provided with evidence explaining how this prodigious alleged lie was contrived: i.e. a secret first marriage to a named individual from among the leading nobility of the realm. Not only did Elizabeth Woodville fail to denounce any of this, even after Richard’s death, but neither did Lady Eleanor’s relatives even mention it let alone repudiate the evidence, whether after Eleanor’s death, or Edward IV’s, or Richard III’s.

Had Stillington’s testimony been perjured, it would have been perjury in the most public and disgraceful way possible from one of England’s foremost bishops, who had been close enough to Edward IV to have enjoyed the office of Lord Chancellor for several years (and received no special mark of favour after the denunciation).

In terms of the law this was a case of precontract, i.e. an existing marriage being a legal impediment to a later marriage.[10] Cases like this, with the concomitant bastardization of the offspring, were not unusual in view of the surprising informality with which a binding sacrament of marriage could be undertaken by a couple in complete privacy. Hence the Church’s insistence on banns to prevent secrecy, which Edward IV violated with both his known marriages.

In this area Professor Richard Helmholz is our best and most accessible authority.[11] For offences against the Church there were often ways open to high-placed individuals to set aside the implications: e.g. Edward IV might have had his first secret marriage annulled. Further, the Church itself recognized an inherent unfairness when the consequences of invalid liaisons led to the offspring suffering deprivation, and there were routes available (upon application) to have their bastardy set aside. However, in Edward IV’s case there were two insurmountable obstacles, even in the malleable reckoning of the Church: first, he had died without making any such suit to Rome, and second, it wouldn’t have been granted after 1464 because of the calculated secrecy of his second ‘marriage’ which placed the situation beyond redemption.

In the common law courts, when legitimacy/illegitimacy needed to be determined, a case would typically be adjourned while referral was made to a bishop for adjudication under canon law. On receiving a judgment, proceedings were then resumed under common law and questions of inheritance decided, over which the Church had no jurisdiction. Interestingly, Helmholz points out that by the 1480s the practice of referring bastardy cases to the ecclesiastical courts had been largely abandoned on the Continent, and was by no means universal in England; so those who queried the jurisdiction of a lay court were somewhat behind the times. Of course, when it came to inheritance of the throne of England there was no higher tribunal to determine this urgent question than the Three Estates of Parliament.

In June 1483, within this legal framework, there had been a process which consisted in four parts, all of which posterity has seen fit to lump into a single (usually disparaged) decision.

* First, the King’s Council of the Protectorate was presented with evidence by Bishop Stillington, almost certainly around 9 June,[12] to the effect that in the eyes of the Church Edward IV’s Woodville ‘marriage’ had been invalid and its offspring were illegitimate. Under the common law such illegitimate children were barred from inheriting anything. With a succession crisis on hand, it must now be resolved urgently and definitively whether an illegitimate child could ascend the throne, with all the attendant risks of a tainted dynasty.

* Second, this would certainly have been put to the foremost experts in canon and secular law and matrimonial litigation. The Council deliberated over this for 8–10 days, eventually deciding on 17 June that the problem was serious enough to postpone Edward V’s coronation and Parliament until November. The Three Estates of Parliament were now gathering in London in response to writs to attend the session (25 June) which was to have followed the scheduled coronation (22 June). The dilemma was duly remitted to the Three Estates during this period (the week of 16 – 21 June).

* Third, a verdict of illegitimacy barring Edward V from succeeding to the throne was reached in this forum (which included the Lords Spiritual) by 21 June, and sermons to that effect were authorized to be given on Sunday 22 June in the usual public places.

* Fourth, the Parliament/quasi-Parliament/Three Estates assembled officially, probably on the previously summoned date of 25 June. During this assembly they drew up a written summary of the case and their agreed verdict,[13] which they used as the basis for their next decision, i.e. that an untainted successor for the throne must be chosen, and that person was Richard of Gloucester. They framed a petition to be presented to him next day, 26 June.

It can be seen from this time-frame that the succession problem had been thoroughly examined by leading representatives of the government. Because it had momentous implications, the full case and the verdict needed to be formally adopted and recorded in writing by the quasi-Parliament on 25 June[14] before a replacement for Edward V could be considered. This latter process required discriminating between possible heirs, of whom Edward Earl of Warwick was a leading candidate by male primogeniture as well as Richard Duke of Gloucester. Once the decision was reached that Warwick was barred by his father’s attainder, all these points were incorporated to form the major part of the petition handed to Richard, which was later inserted into the overall Act Titulus Regius.[15]

A test of the quasi-Parliament’s proceedings

To test the robustness of these proceedings in 15th-century parliamentary terms, we must establish whether this deliberating body (Council + quasi-Parliament, as constituting the government) carried lawful authority when not sitting in conventional form of Parliament.

I have accordingly sought earlier historical parallels, because lawful authority at this time should be understood to mean precedent. E.g. I would point to irregular decision-making in the recent Lancastrian past, particularly that in 1399 when the manufactured abdication of Richard II was recognized and Henry of Bolingbroke made king.

Then in 1422 the King’s Council, on its own authority, revoked Henry V’s provisions for a regency for his son and instead established the office of Protector and Defender of the Realm. And later, when Henry VI fell into a catatonic state in 1453 and took no part in proceedings, the Parliament took decisions into its own hands by appointing (and subsequently re-appointing) the Duke of York as Protector and Defender while rejecting claims by the queen to govern on her husband’s behalf.

As recently as 1460 there was the case relating to the disinheriting of Henry VI and his son. Members of the parliamentary establishment shamelessly hid behind a succession of excuses not to involve themselves in determining the rightful inheritance of the crown, when the Commons, justices and law officers couldn’t be seen for dust. The Lords alone constituted the adjudicators on the rights of the incumbent king ‘by thauctorite of this present parlement’, unlike the proceedings of 1483 when all members of the Three Estates were represented.

In awarding the succession to York in 1460, the verdict of the Lords, acting alone, was accepted and implemented as the just outcome. This provides a very useful pointer to the thinking in 1483. Crimes, in English Constitutional Ideas in the 15th Century, attributes the acceptance of York’s claim to the irresistible magnetism of primogeniture: ‘... belief in royalty as conferred by birth was far too strong, far too ancient …’.[16] The Duke’s argument was that his ancestor Lionel, Duke of Clarence, was by birth an elder son of Edward III, compared to the incumbent junior Lancastrian line which descended from a younger son. Given this context, we should ask what would have been the verdict if Lionel had been an elder but illegitimate son? If we were to apply to Lionel’s birth the circumstances of Edward V’s birth, would the Lords have admitted York’s claim?

Chrimes, who subscribed to the traditionally jaundiced view of Richard III prevalent in the 1930s, sourly admitted that under the precedent of 1460 it might be possible to obtain a title ‘by procuring the bastardization of the alleged heirs’; his references to the precontract case suggest that he views it as a pretence, while offering no evidence for this view. Indeed he does not discuss the quasi-Parliament’s judgment of June 1483 except to observe that it continues the growing concept of looking to the Three Estates as the ultimate authority.

Titulus Regius: recapitulating and reaffirming the decisions of 1483

By November 1483 the postponed Parliament had to be delayed again when the October rebellion (‘Buckingham’s Rebellion’) had to be quelled, so it was not until January 1484 that the Act known as Titulus Regius was presented by the Three Estates to the Three Estates, now reassembled in form of Parliament. Here the petition was resurrected and reproduced as the central part of the instrument recapitulating and endorsing Richard’s succession. The underlying aim was to seal it with this Parliament’s official imprimatur, which now served to remove any lingering doubts. The very wording of these comments makes it clear that the Act is confirmatory, not sui generis.

Chrimes’s comments on the Act of Succession are instructive. The pre-existing election of Richard III was ‘ratified’ in the Act: ‘The election was said to have been made by the three estates out of parliament, and the parliament [of 1484] merely confirmed’ this extra-parliamentary proceeding. ‘There was no allusion to a title by parliamentary act’ [my emphasis], in fact the original description of the Act called it ‘a recapitulation’ of his title.

This has been my argument all along. The Act known as Titulus Regius did not create or legislate Richard III’s entitlement to the throne, it was a ratification and reaffirmation of the status quo. Therefore Henry VII’s repeal of the Act did not annul Richard’s pre-existing title, nor did it rescind the legal grounds that underlay it.

Although Titulus Regius is itself too lengthy to be quoted in full, we should at this point discuss what the Act says and how it describes its purpose.

* It opens with the statement that before the coronation of ‘oure Souveraign Lord the King’, a parchment roll [the petition to accept the crown] had been presented to him containing certain articles.

* It had been presented on behalf and in the name of the Three Estates of the Realm comprising many and divers of the lords and nobles and notable persons of the commons in great multitude.

* Since that same body [in June 1483] had not sat ‘in fourme of Parliament’, certain doubts, questions and ambiguities had arisen in the minds of some people. Hence, to the perpetual memory of the truth …

* ... ‘bee it ordeigned, provided and [e]stablisshed … now by [authority of] the same Three Estates assembled in this present Parliament’ (my emphasis) that the purport of the petition ‘… bee ratifyed, enrolled, recorded, approved and auctorized’, for the removal of dubiety …

* … with the result that everything specified [in the petition] ‘be of like effect, vertue and force as if all the same things had been so affirmed … in a full Parliament’.

* The contents of the petition are then set out: ‘To the High and Myghty Prince Richard Duc of Gloucester’ etc. The petition ends ‘… to the comforte and gladnesse of all true Englishmen.’[17]

* After this the Act continues: ‘… the Right, Title and Estate’ enjoyed by King Richard are just and in accord with the laws of God and Nature and the Customs of this Realm; however, it is recognized that ‘the most parte of the people of this Lande’ are not sufficiently learned in those laws and customs, so that the truth and right may not be clearly known to all and may consequently be questioned.

* Knowing that any declaration of truth or right made by the Three Estates assembled in Parliament ‘removeth the occasion of all doubts and seditious language’, therefore, at the request and by assent of the Three Estates re-assembled in this present Parliament [i.e. the same people who created the petition in the first place] ‘bee it pronounced decreed and declared’ that King Richard was and is undoubted king ‘as by lawefull Elleccion, Consecration and Coronacion’.

The remainder of the Act pronounces that the throne is vested in King Richard ‘and after his decesse in his heires of his body begotten’. It is crystal clear, therefore, that its purpose is to set the seal of this Parliament on a matter that has already been debated, decided and put into effect several months earlier by the same Three Estates (themselves), whose re-assembly in 1484 now desires to banish any lingering doubts. It’s hard to see how the thing could be any clearer.

The Tudor king’s repeal process

In terms of our centuries of interaction between Parliament and the courts, particularly since England is underpinned by such a large body of common law, it is recognized that Parliament does not legislate in a vacuum. Laws enacted or repealed sit within a vast body of existing law, so it is necessary to introduce specific legislation (and/or make adjustments) to cover any gap or conflict created by a repeal. If nothing of this sort is done – and when Titulus Regius was repealed no associated legislation was enacted – the position simply reverts to what it was immediately before the rescinded Act originally came into force (January 1484). At the time immediately before Titulus Regius was enacted, the proceedings relating to bastardy, disinheritance and lawful succession by male primogeniture had been legally determined and Richard III had been crowned king and reigned for half a year.

We may compare the extraordinary repeal process adopted by Henry VII with the proper parliamentary procedures today, which would require the Act to be read in Parliament, its repeal agreed, annotated with the date and then archived. I cannot vouch for normal parliamentary practice at the time of Henry VII’s usurpation, but at least some of the latter processes would have been required, if only the reading of the Act that was to be repealed.[18]

In short, all Henry VII’s repeal achieved was to rescind the 1484 Act’s endorsement of Richard’s pre-existing legal succession. The decisions that led to it, including the bastardy determined by the Council and quasi-Parliament in June 1483, were already a fait accompli and had been legally acted upon: Henry VII’s repeal was incapable of annulling them.

To the best of my knowledge no trace of either Church or lay process of law relating to the case of Edward IV’s offspring is recorded in 1485/1486. Nor is there any record of the issue of their bastardy being raised or discussed or debated in the Tudor Parliament. It cannot be claimed, therefore, that the stated intent of Parliament in agreeing to the repeal was to ‘legitimize’ Elizabeth of York. In the Rolls of Parliament there is merely a declaration that this was ‘a false and seditious bill of false and malicious contrivance’:

… The king … wills that it be ordained, decreed and enacted, by the advice of the … lords spiritual and temporal and the commons assembled in this present parliament, and by authority of the same, that the said bill, act and ratification [Titulus Regius], with all the details and consequences of the same bill[19] and act, for its false and seditious contrivance and untruth, be void, annulled, repealed, cancelled and of no effect or force. And that it be ordained by the said authority that the said bill be cancelled and destroyed, and that the said act, record and enrolment be taken and removed from the roll and records of the said parliament of the said late king, and burnt and entirely destroyed. And moreover … that any person who has any copy or remembrance of the said bill or act shall bring them to the chancellor of England at the time, or destroy them entirely in some other way, before next Easter, upon pain of imprisonment and of making fine and ransom to the king at his will, so that all the things said and rehearsed in the said bill and act may be forever out of memory and forgotten. And moreover, be it ordained by the said authority that this act, or anything contained it, be not harmful or prejudicial to the act establishing the crown of England on the king and the heirs begotten of his body. …[20]

The above is a very thin basis for repealing an Act of Parliament, and contains more obfuscation and bluster than argument relating to its supposed harmfulness. Nor does it at any point refer to the bastardy of Edward IV’s offspring or the intention for this to be revoked. Clearly it was desired to give this impression, which those with a vested interest would certainly have encouraged. But it was a false impression. The bastardization of Edward IV’s offspring had been determined long before the Act that confirmed it.

For Henry VII this repeal was quite simply a matter of political policy: it looked good and cost him nothing. It was a piece of sleight of hand designed to appease Yorkist sensibilities, typical of Henry VII’s chicanery as mentioned in footnote 5 above.

Papal assistance

Right from the start, Henry Tudor had benefited hugely from soliciting Pope Innocent VIII to his cause, almost certainly thanks to Bishop John Morton who probably directed Tudor’s political decisions. The only genuine route open to him, had he cared enough to set aside the bastardy of his wife, would have been to order re-examination of the original evidence of the precontract. But if he had hoped to obtain a different outcome thereby, he would have needed the pope to disavow the judgment of a prominent bishop (Stillington) and the Lords Spiritual of the Three Estates, for which unimpeachable grounds would be needed. The Church would not be interested in arguments such as ‘too convenient for Richard III’.

Under prevailing canon law His Holiness couldn’t airily set aside the bastardy of the Woodville children. And however deeply in the king’s pocket Pope Innocent might be nestled, there was no prospect that he would do battle for this newly crowned king who could give no guarantee how long he would occupy England’s throne.

It is widely thought that Pope Innocent declared Elizabeth of York legitimate. This is not so. The pope issued two letters at the relevant time, the first on 2 March 1486, which was the standard papal dispensation (a mere 200 words) for impediments to her marriage with Henry VII:

… The pope, therefore, at the petition of the said king Henry and Elizabeth, who is the eldest daughter and undoubted heiress of the late king Edward IV, and of the said prelates, etc., hereby dispenses them, notwithstanding the said impediments, to contract marriage, cause it to be solemnized and celebrated, without banns, as shall please them, even in a time prohibited by the Church, consummate it, if it shall please them, and remain therein, the offspring thereof being hereby pronounced legitimate. …[21]

The phrase ‘undoubted heiress’ was a description the pope chose to enter into his document, but it was irrelevant to the purpose in hand.[22] Elizabeth was addressed as the eldest daughter of Edward IV, but of course a bastard daughter was still, in law, a daughter. Whether she was ‘undoubted heiress’ meant precisely nothing in any legal sense in this document, since such matters were beyond the Church’s expertise and jurisdiction, i.e. matters for English law which always had the final say on inheritance. Indeed, to be described as an heir did not signal that one was legitimate: it was not uncommon for a bastard to be made an heir or heiress, for example, by settlement within the family.

This dispensation was clearly not sufficient for the insecure Henry VII, whose agents at the Vatican were soon busy persuading Pope Innocent to issue a Papal Bull whose sole purpose was to keep him and his Tudor dynasty on the throne in every possible circumstance. One such circumstance was even if Elizabeth died and he remarried (so much for any heritable rights of hers!).The Bull was issued on 27 March, but nothing in it touched on Elizabeth’s legitimacy. There were two references to her, the second comprising three words (‘the said Elizabeth’). Here is the first:

… Pope Innocent VIII … By the Counsel and consent of his College of Cardinals approveth confirmeth and establisheth the matrimony and conjunction made between our sovereign lord King Henry the seventh of the house of Lancaster of that one party and the noble Princess Elizabeth of the house of York of that other party with all their Issue lawfully born between the same …

This was merely an acknowledgement of Elizabeth’s courtesy title and again conferred no rights of legitimacy: she was by now queen consort, and it was customary to use the term ‘prince’ for members of royalty. The Tudor influence was evident in its wording which, like that of the dispensation, conspicuously repeated Henry Tudor’s spurious claim to the title of Lancaster.

Of course Henry VII did have another recourse had he wished to de-bastardize his wife, which would have been to replicate Richard II’s Act of Legitimation in 1397 for the bastard Beaufort offspring of John of Gaunt.

At this point it would be useful to explain Henry VII’s heritage. He was in fact a great-grandson of one of that bastard Beaufort clan who had been legitimated by Richard II. But they had been legitimated in name only. King Richard’s edict gave them no rights of inheritance; so they and their heirs had no claim on the succession to the throne, which Henry IV took care to make clear in writing in 1407. And being from a bastard line, they and their heirs had never been scions of the house of Lancaster either: Henry VII’s claims were a sham.

Despite Pope Innocent’s embarrassing eagerness to bolster the Tudor regime, His Holiness could do nothing to annul Elizabeth’s bastardy, just as Pope Boniface IX had found no way to annul the bastardy of the Beauforts in 1396, though many writers of history have assumed he did.[23] Sometimes a bastardy was just too notorious.

So Henry VII could have emulated Richard II, though this would inevitably have called to mind his own ancestor’s bastardy and disqualification from the succession. It would also have necessitated his admitting his wife’s pre-existing bastardy in a very public way, and cancelling it by royal edict alone, when he himself had been ‘royal’ for just four months. Furthermore, any such decree of legitimation placed before Parliament would either have to legitimate all her siblings too, as Richard II had done for all the Beauforts, or explain (again in a very public way) why he had excluded them, which could have opened up some unwelcome complications. Small wonder that he chose not to follow this route.

Outcomes for the Missing Princes

Speaking of unwelcome complications, where did the missing princes stand after the repeal? This is where it’s mistakenly assumed that it ‘automatically rendered them legitimate’. Obviously this did not happen, any more than it happened for their sisters, but the position was far more nuanced for the princes. Thanks to ingrained ideas of male primogeniture these brothers were regarded as very special, and as vessels of the royal blood even though still illegitimate.

When Edward V lost his place in the succession in 1483, Richard III had represented the appropriate successor of senior legitimate royal rank and proximity within the royal family. But circumstances had undergone a somersault when Richard was defeated by a Tudor interloper who seized the throne, usurping the established bloodline. His bold pre-invasion claims of hereditary right failed to feature in Parliament’s assent to his sovereignty in 1485, and the age-old passage of the crown to the nearest male relative had been overturned in favour of a line prohibited from inheriting it. The crown had effectively became a prize to be won in battle by whoever could defeat the present incumbent.

So when two pretenders to Henry VII’s throne came along at the head of armies in the 1480s and 1490s, claiming the identity of the two missing princes, loyal Plantagenet adherents were free to espouse their cause: for them, even an illegitimate son of the blood royal possessed a status far superior to the Tudor intruder. Hence there were no caveats among those who supported them. Their lineage was known and respected, and when they showed themselves willing, they became the chosen challengers leading the charge.

Indeed when the first such pretender appeared, challenging in the name of King Edward, pre-eminent among the lords who supported him was the Earl of Lincoln who would have been the senior heir of the legitimate Plantagenet line. But Edward V had been prepared and groomed for kingship, and at one time recognized as king. He had lacked a coronation in 1483, but that could be supplied in 1487 when he was crowned in Dublin.

This is not the place to go into details about the pretenders’ credentials, but there was remarkable evidence that some of the highest in the realm, and in European realms, staked their lives and fortunes on the return of Edward V and Richard of York, for whom it was enough that Plantagenet blood flowed in their veins. Not only did Thomas More remind his readers that some people believed they had outlived Richard’s reign, but also Vergil and Bacon noted common reports that they had been ‘conveyed secretly away and were yet living’; indeed Bacon added that the memory of King Richard ‘still lay like lees at the bottom of men’s hearts’.

APPENDIX

Year Book 1 Henry VII Hilary Term Plea 1 fol. 5v

Richard Tottel printing of 1555 transcribed and translated by Annette Carson, 26.2.2024

Note that for clarity, two extracted passages have here been rendered in bold with inverted commas. The first being the opening address of the petition (referred to as the ‘bill’) as contained within Titulus Regius, and the second being the opening sentence of Henry VII’s repeal.

Translation

All the Justices in the Exchequer Chamber, on the first day of the [Hilary] term, by the king’s command discussed the reversal of the bill and Act that bastardized the children of King Edward IV and Elizabeth his wife. The Justices took the king’s direction, for as much as the bill and Act were so false and slanderous that they would not wish to rehearse the matter, nor the effect of the matter, save only insofar as that Richard, formerly Duke of Gloucester, and then in fact not by right King of England, had made a false and seditious bill to be put before him, which begins thus:

“Pleaseth it your Highness to consider these articles ensuing etc.”,

omitting any further rehearsal … which bill afterwards in his Parliament held at Westminster was confirmed and authorized etc.

“The King, at the special request and prayer of his Lords Spiritual and Temporal and the Commons assembled in this present Parliament, and by the authority of the same, wills that the said Bill, Act and Record be annulled and utterly destroyed, and that it be ordained by the same authority that the same Act and Record be taken out of the Roll of Parliament and be cancelled and burnt, and be put in perpetual oblivion. Also the said bill with all the appendancy etc.”

And this was the consideration of the Justices, that they rehearsed no more of the matter, so that the matter might be and remain in perpetual oblivion for the falseness and shamefulness of it. And if any part of the speciality [= that which is specified] of the matter had been rehearsed in this Act, then had it [= it would have] remained in remembrance always, which was thought by all persons that it should in no wise be, etc.

Note that this is the policy.

Note likewise that it [the repealed Act] may not be taken out of the record without an Act of Parliament for the sake of the indemnity and jeopardy of those having the records in their keeping, the which was assented, and for all discharges the authority of Parliament is required.

And that very day this was read in the Parliament Chamber before the Lords and the Judges; and the Lords thought well of this and would grant it. But there was a move by some of them that it would be good practice for whoever had made this false bill to reform it, and they said that the Bishop of B. made the bill, and the Lords would have him in the Parliament Chamber and have him answer for it. And the King said that he had pardoned him and for that reason he no longer wished it.

Note the king’s constancy.

And some bishops were against this, etc.

Transcription

Toutes les Justices en lescheker chamber primo die Termini par le commaundement le roy comminerunt pur le reversell del’ bill & act que bastard les infantes le roy E. 4. & Elezabeth son femme. Et pristerount son direccion, pour ceo que le bill & lact fuit cy faux & slaunderous que ils ne voill’ reherse le mater, ne l’ effect del’ mater, mes tantsolement que Ric jadz Duc de Glouc’ & puis en fait & nient in droit roy dengleter’ fist un falx & Seditious bill’ pur este mis a luy que commence sic;

“Pleaseth it your highness to consider these articles ensuing, &c.”

sauns pluis rehersell , whiche byll afterwarde in his parliament holden at Westminster was confirmed and auctorised, &c.

“The Kyng at the special request and praier of his Lordes spirituall and temporal and the comons of this present parliament assembled, and by the auctoritye of the same, that the said bil act and recorde, be adnulled and utterly destroyed & that it be ordeined by thesame auctorite, that the same act and record be taken out of the rolle of parliament & be cancelled & brent & be put in perpetual oblivion & also the said bil with al the apendancye, &c.”

& this was the consideracion of the Justices that thei rehersed no more of the matter, that the matter might be and remain in parpetual oblivion for the falsenesse and shamefulnes of it, & if any part of the specialtie of the matter had bene rehersed in this acte, then had it remained in remembrance alwaie, whiche was thought by al parsons that it should in no wise be, &c.

Nota icy bien le policy. Nota enseint, que il ne puissoit este pris hors del record sans act del parlement pur le indemnite & jeopardie de eux que av’ les recordes en lour gard’ qux fuero’t(?) assente a ceo, & purs toutz discharges il fuit par auctoritie de parlement.

Et mesme le jour ceo fuit lie en le parliament chamber devaunt le seigniours & l’ Juges. Et les seigniours pensoint bien de ceo & graunteront a ceo. Mes fuit move per ascun del eux que serra bon order, que cesty que fist ceo faux bil refourmera ceo, & disoint que le evesque de B. fist le bill, & les seigniours voillont aver luy in le parliament Chamber pour aver luy responder a ceo.

Et l’ roy disoit que il aver luy pardon & pur ceo il ne voilt’ puis fair’ a luy qo’ nota constancia regis, & quidam episcopi fuerunt contra ipsum, &c.

[1] I am unable to guess the exact legal meaning of these terms.

[2] Of course for those involved, the date was January 1485; I am using the New Style dating system.

[3] My preference is for the term ‘Act of Succession’ rather than ‘Act of Settlement’, the latter being the title given to the Act of 1701 enacted to ensure England’s crown was settled exclusively on Protestants.

[4] See my article on the subject at https://annettecarson.com/content/ item 19.

[5] Examples include the spurious predating of his reign and associated Acts of Attainder, and legal shenanigans to curb the right of peers to be tried by peers. Compare also the wholly unlikely aliases invented for the pretenders who challenged his throne. And in terms of propagandizing Richard III’s ordering of the murder of the so-called ‘princes in the Tower’, Francis Bacon averred that it was Henry VII who ‘gave out’ the allegation recorded by Thomas More (unsupported by any historical record) that James Tyrell confessed to the murder on Richard’s orders. This king was also the first of those Tudor monarchs who cynically broke their own promise of safe-conduct when it suited them.

[6] Under the reign of Richard III the royal house of Portugal was happy to offer her the hand of their Duke of Beja.

[7] Court of Exchequer Chamber Year Book, 1 Henry VII, Plea 1 of Hilary Term. Appreciation to Professor David Seipp, Boston University for his advice and for kindly supplying the 1555 version; also to David Johnson for supplying a number of papers at my request.

[8] Richard III (Eyre Methuen, 1981), p. 90. Ross failed to take into account the training of mediaeval lawyers in the techniques of rhetoric, where the clinching argument is saved till last.

[9] Lords Spiritual listed as absent included Canterbury (the elderly and unwell Bourchier) and Bath &Wells (Stillington of course), Salisbury, Carlisle and St Asaph; according to W.E. Hampton, Henry VII excluded his political opponents: The Ricardian, Sept. 1976. It is intriguing that some of those present dared to disagree with Henry VII’s refusal to bring in Stillington for questioning. Many of these clerics had been among the Three Estates who believed and endorsed the grounds for the bastardization in June 1483: one would imagine it was better for them to have remained silent … unless they still believed their colleague and thought the case should be re-examined?

[10] The term ‘precontract’ is widely misunderstood. The ‘contract’ refers to the previous marriage, not a betrothal or a piece of paper with signatures on it. A marriage could be concluded by the two parties exchanging simple words, or by the promise of marriage if this was followed by consummation (as in Lady Eleanor’s case).

[11] ‘The Sons of Edward IV: A Canonical Assessment of the Claim that they were Illegitimate’, Loyalty, Lordship and Law (Richard III & Yorkist History Trust, 1986), pp. 91-103. See also Helmholz, ‘Bastardy Litigation in Medieval England’, American Journal of Legal History 13 (1969) pp. 360-83.

[12] See Simon Stallworth’s report of meeting, Stonor Letters and Papers, 1290–1483, ed. C.L. Kingsford (1919), ii, pp. 159–60.

[13] Bracton emphasizes the need for clearly specified reasons for an allegation of bastardy to be recorded, owing to the dichotomy between the Church and secular courts: Bracton de Legibus et Consuetudinae Angliae, ed. G Woodbine, trans. S.E. Thorne (4 vols., Cambridge, Mass., 1968-77), IV p. 285.

[14] We may be confident that the vast majority of those originally summoned for 25 June were present. Though postponed on 17 June, it had been too late to prevent the arrival of myriads of planned attendances at both coronation and Parliament, and Mancini (p. 67) reports their large numbers. It appears one or two writs of cancellation went out but their issuance was soon stopped.

[15] These distinct processes should never be conflated. The governing bodies of Council and Parliament (and their lawyers) knew exactly the established legal and judicial procedures they had to follow. But posterity has been denied the assistance of any surviving government records in piecing these events together: see for example the wide divergence of reports of what was said in the sermons of 22 June: collated in Carson, Richard III: The Maligned King (The History Press, 2013, 2023) pp. 117–20. What is certain is that Edward V was proclaimed illegitimate and his succession set aside. Exactly what was said by the preachers about Richard replacing him is open to debate.

[16] CUP, 1936, pp. 29–32.

[17] The full text can be found online, an accessible version being on Wikipedia. Note that although it would have incorporated an accurate recapitulation of the petition, it need not have repeated every word of the original (which is no longer extant). Quite likely witness testimonies were omitted or put into annexures.

[18] Ex informatio House of Commons Library, 14 February 2024, with acknowledgements also to Sandra Pendlington.

[19] A more confusing translation gives ‘all the circumstances and dependants of the same bill’; either way this catchall phrase is supposed to mean ‘all the contents and implications of the bill’ (see also footnote 17 above.

[20] ‘Henry VII: November 1485’ 18. [23.] in Parliament Rolls of Medieval England, ed. Chris Given-Wilson et al (Woodbridge, 2005), British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/no-series/parliament-rolls-medieval/november-1485 [accessed 25 January 2019].

[21] 1485/6 6 Non. March (2 March) St Peter’s, Rome. (fol. 412r) in Calendar of Papal Registers Relating To Great Britain and Ireland: Vol. 14, 1484-1492, ed. J.A. Twemlow (London, 1960).

[22] Henry Tudor had already presumed to obtain exactly the same dispensation in a furtive manner in 1484, concealing his and Elizabeth’s names and antecedents; not the slightest attention was paid by Rome, in the granting thereof, to whose heir or heiress they were. Such matters were extraneous to Rome’s sole interest which consisted in taking statements of kinship and making the marriage possible.

[23] Contrary to popular assumption, Pope Boniface IX did not retrospectively render the Beauforts legitimate in the eyes of the Church when their adulterous parents eventually married. His apostolic letter explicitly states that he declares legitimate any offspring ‘received and to be received from this marriage’ [of Gaunt and their mother]: prolem ex hujusmodi matrimonio susceptam et suscipiendam (my emphasis). The Beauforts were born before their parents’ marriage.

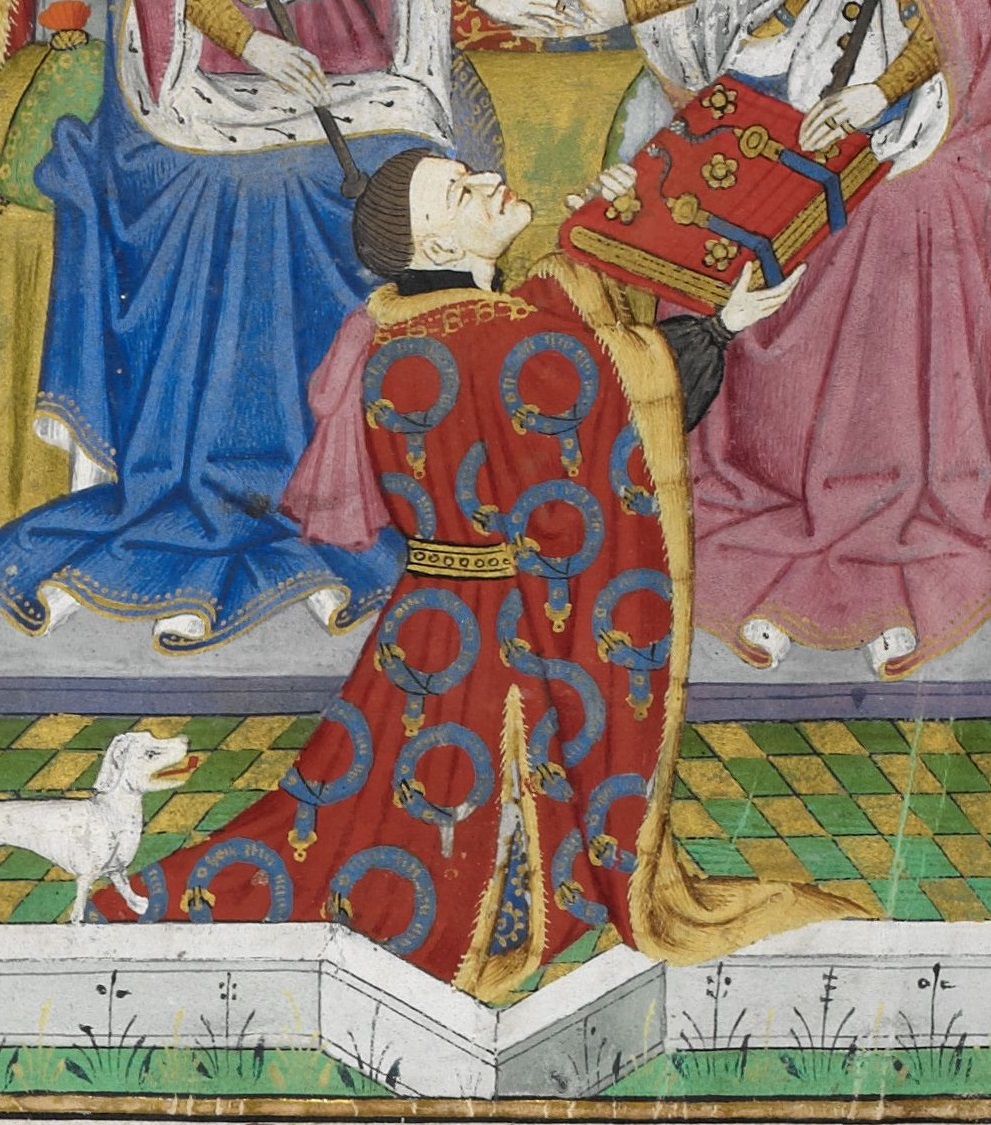

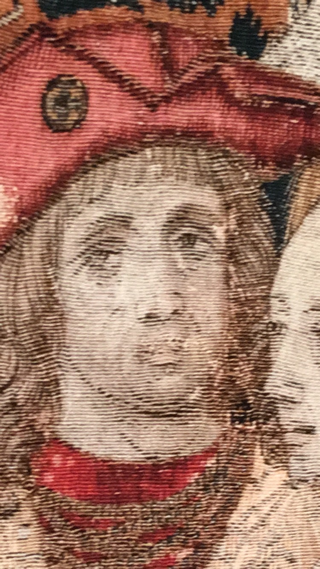

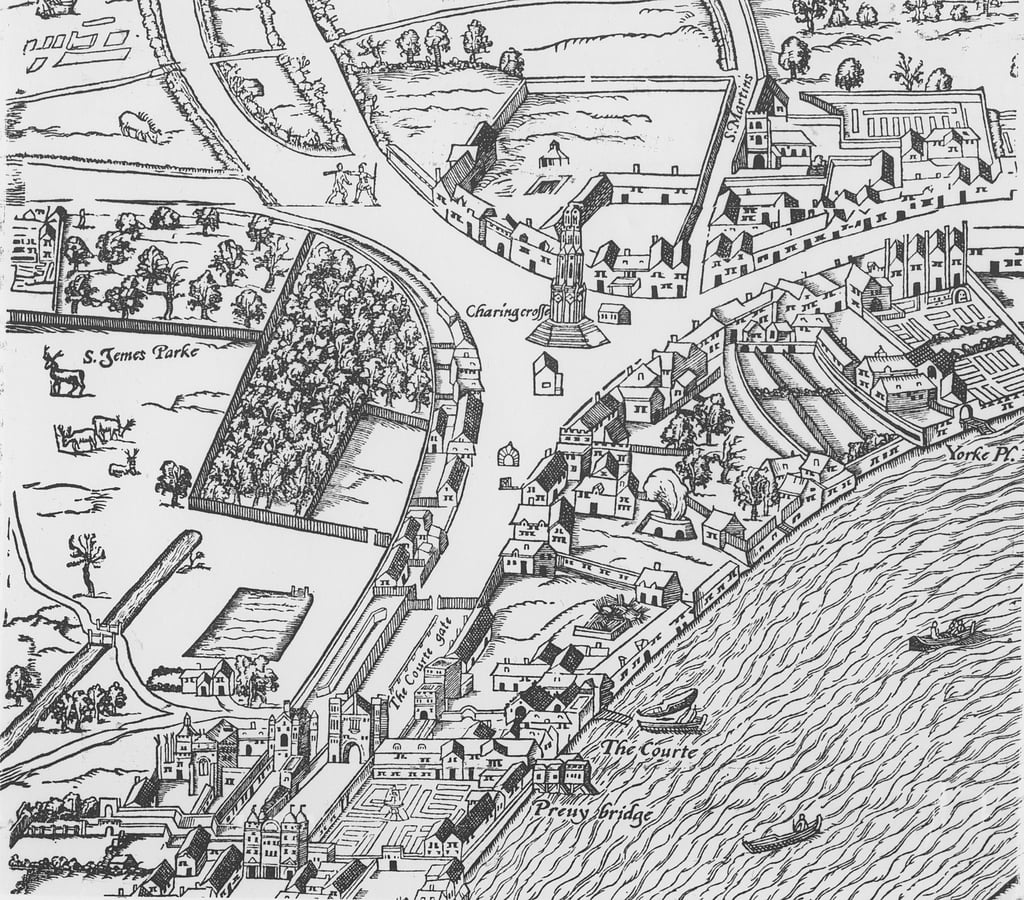

Artist’s impression of the offer of the Kingship to Richard, Duke of Gloucester, Baynards Castle by the Three Estates of the Realm. Mural in the Royal Exchange. Artist Sigismund Goetz.

Artist’s impression of the offer of the Kingship to Richard, Duke of Gloucester, Baynards Castle by the Three Estates of the Realm. Mural in the Royal Exchange. Artist Sigismund Goetz.