Could these images in Coldridge Church be of the same man? A young Edward V, an adult man whose face appears to show injury/disfigurement around the mouth/chin area and the face of the John Evans effigy which also seems to have a scarred chin? Photo thanks to John Dike, leader of the Missing Princes Project, Devon.

It was way back in 2020 that I was first alerted to what I now call the Coldridge Theory by an article on the lovely Devon Churchland website. Following on from that I researched further and wrote my first post on the theory which has now been viewed over three thousand times, so I know that many of you reading this may already be familiar with the story. Rather than scrolling away I would ask you to please bear with me. In the course of my research I came across other links that strengthened the theory particularly the pivotal role of Sir Henry Bodrugan to which I will return to later. Now and again I come across people dismissing the theory out of hand because, they insist, the princes disappeared on Richard’s watch ergo he must have murdered them despite there being not the slightest scintilla of evidence that such a crime was ever carried out. Thus I find Coldridge in itself being dismissed without any further thought given, unfortunately, to the other equally important links and participants that strengthen the theory – which although still unprovable – becomes at the least very plausible. And here’s a thing – ironically when all the leads are considered the theory has more going for it than the tired old chestnuts still being trotted out that Richard was guilty of this atrocious crime or if not murdered by him then they were done in by either Henry Tudor, who was not in the country at the time, or his mother, Margaret Beaufort, which is equally absurd and unsupported but there you go. Some people simply refuse to remove their head from the sand which is a great shame as just a small amount of research can uncover intriguing possibilities that the princes were murdered by no one but sent to places of safety. An example of these blinkered and dated views is when you ask these naysayers what they think about the crucial role Sir Henry Bodrugan played in the story – no answer comes the stern reply. It is for this reason that I’m now going to approach the theory from a different angle – this time in the date sequence that notable incidents occurred – a reappraisal and fresh collation aimed at those who may know some but not all the story if you like. I hope you will stick with me. So back we go to the beginning:

Dramatis Personae:

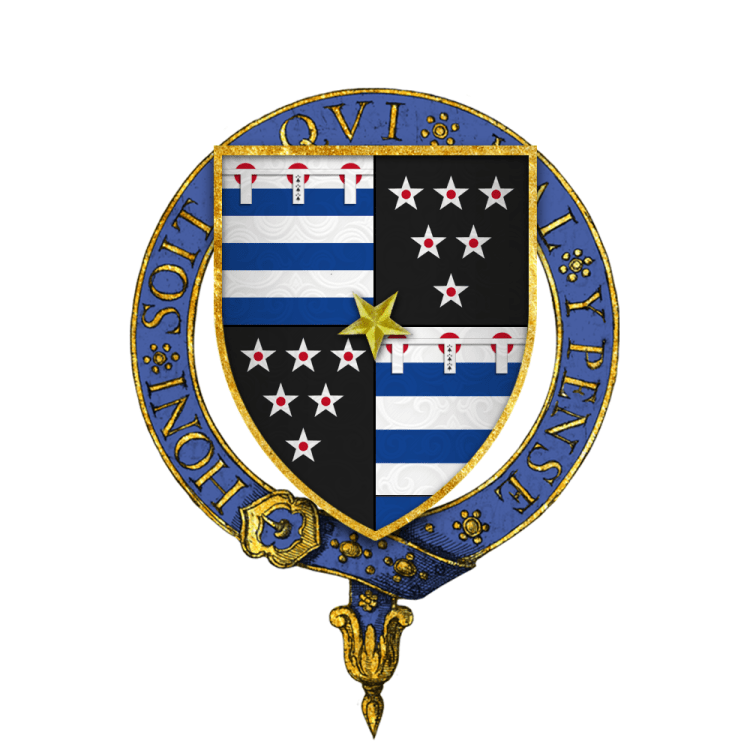

Sir Henry Bodrugan/Bodryngham One of the most powerful men in Cornwall. Popular with both Edward IV and Richard III. Crucially one time owner of Coldridge Manor and Park – granted to him by Richard in April 1484.

Thomas Grey, Marquess of Dorset: Elizabeth Wydeville/Woodville’s eldest son by her first husband, Sir John Grey. Thus half brother to Edward V. Owner of both Coldridge and Gleaston Castle via his marriage to wealthy heiress Cecilia Bonville Coldridge was confiscated from him in 1483 but returned in 1485 by Henry VII after Bosworth.

Edward V: Became king aged 12 on the death of his father Edward IV in April 1483.

Sir Robert Markenfield/Markynfeld: Loyal follower to King Richard III. Sent to Coldridge on the 3 March 1484 two days after Richard swore an oath on the Ist March that neither Elizabeth Wydeville nor her daughters would be harmed if they came out of sanctuary and thus the likely date she did indeed depart from the sanctuary with her daughters. Sir Robert’s brother, Thomas, was also a loyal follower as well as personal friend to Richard III, and rewarded generously by the king for his services.

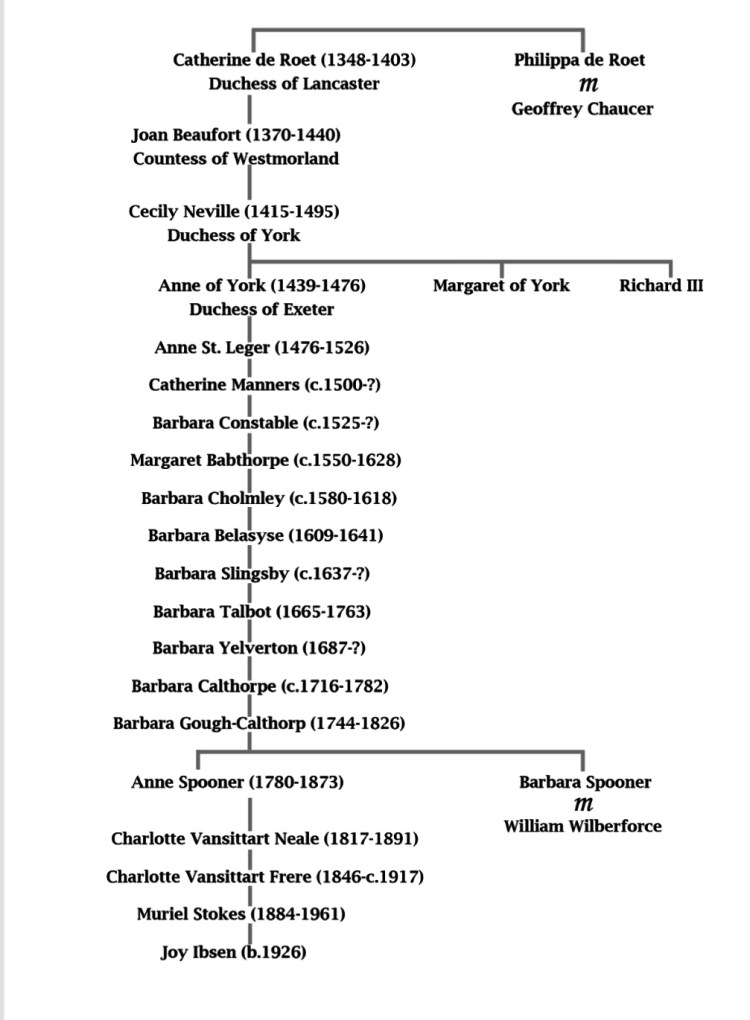

Cecilia Bonville: The wife of Thomas Grey. A wealthy heiress and courtesy of his marriage to her, Thomas became owner of both Coldridge and Gleaston Castle, as well as numerous other properties. Cecilia had wall to wall familial Yorkist links.

Elizabeth Wydeville/Woodville. Edward IV’s queen. Mother to two sons by her first marriage to Sir John Grey, Thomas and Richard, two sons by Edward, Edward V and Richard of Shrewsbury and several daughters including Elizabeth of York who went on to become Henry VII’ s queen. After a royal council meeting in early February 1487 to discuss the rebellion led by the Yorkist leaders she was sent to live out the rest of her days in Bermondsey Abbey.

Elizabeth Wydeville’s portrait from the Royal Window, Canterbury Cathedral.

EVENTS

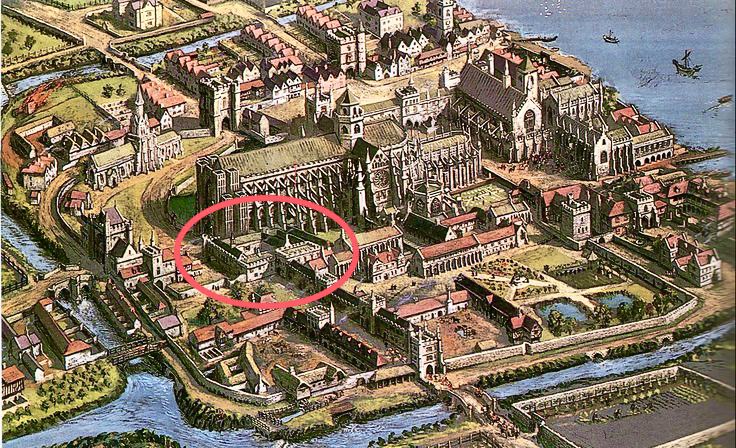

Atmospheric old photo of the archway leading out of Abbot’s court, where Cheyneygates stood, to the cloisters and outside world. Elizabeth Wydville and her family would have walked through this arch during their stay at Cheyneygates.

APRIL 1483 Edward IV died unexpectedly at his palace of Westminster. His Queen, Elizabeth Wydeville, and her Wydeville family were immediately galvanised into action, attempting and failing to both gain control of the young Edward V, who was at Ludlow at the time, and to outmanoeuvre his uncle, Richard of Gloucester before he could arrive in London to take control of the situation in his legal role as Lord Protector. Upon their enterprise failing, Elizabeth, her youngest son, ten year old Richard and his sisters, along with her son by her first marriage, Thomas Grey, beat a hasty retreat into the sanctuary of Cheyneygates, the Abbot’s luxurious house within the precincts of Westminster Abbey. However it was not long before Thomas made his escape and joined Henry Tudor in Brittany. It was at this point Coldridge was removed from the ownership of Thomas and granted to Sir Henry Bodrugan. I will return to this later. Elizabeth was later persuaded to allow Richard to join his brother Edward V, who was by then staying in the royal apartments at the Tower of London. Richard was later reported by Simon Stallworth, the Mayor, in a letter dated 21 June to William Stonor, to be ‘blessid be Jhesus, mery‘ while it was also mentioned in the Great Chronicle of London the young brothers were both seen practicing their archery at the butts and ‘playing in the garden of the tower at sundry times‘ (1).

However before the young Edward V could be crowned a ‘precontract’ was revealed – possibly by Robert Stillington, Bishop of Bath and Wells. This precontract was basically an earlier marriage that Edward IV had made with Lady Eleanor Butler, nee Talbot daughter of John Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury, which, obviously, left him unfree to marry anyone else. The simple crux of the matter was the almost casual ease with which medieval marriages could be made with no need for priest or witnesses to be present. All that it needed was for A to say to B ‘I take thee B to be my wife’ and B to say to A ‘I take thee A to be my husband’ – consummate it and bingo! – you were wed. Of course it was a good idea – especially if you were a king or marrying one, particularly Edward IV – to make sure you did ensure you had witnesses and a priest present in case of later problems occurring. Which they certainly did in this case. The cat was out of the bag and basically Elizabeth was up the Swanee without a paddle – the children she had with Edward were, under the medieval Canon Law of the time, declared bastards and thus ineligible to succeed to the throne. The Three Estates of the Realm having ‘accepted the legality of Edward IV’s first marriage to Lady Eleanor Butler, and consequently, the bigamous nature of Edward’s subequent union with Elizabeth Wydeville’ petitioned Richard Duke of Gloucester, who was next in line, to take up the throne. Richard accepted and was duly crowned King Richard III on 6 July 1483 (2) For those who would like to delve further in this matter you will find it all in TITULUS REGIUS.

A wonderful artist’s impression of the offer of the Kingship to Richard, Duke of Gloucester, Baynards Castle by the Three Estates of the Realm. Mural in the Royal Exchange. Artist Sigismund Goetz.

Soon after his coronation, perhaps too soon and before he had fully consolidated his position, the King with Queen Anne, left London, turning Northwards to go on a progress. It was shortly after this an abortive attempt was made to ‘rescue’ the boys from the Tower. This resulted in them, understandably, becoming more withdrawn from view until further sightings of them dried up altogether. They simply disappeared. This, perhaps not surprisingly, led to rumours arising of their deaths, although no bodies or graves were ever found, and no requiem masses performed for them either. We can safely dismiss the ludicrous and lurid story later penned by Sir Thomas More – who grew up in the household of Cardinal John Morton, Richard III’s nemesis, which frankly, only need be read if you are in need of a laugh.

Ist MARCH 1484. Close to this date Richard and Elizabeth reached an agreement and on the Ist March Richard publicly swore an oath promising that if Elizabeth and her daughters were to leave sanctuary and her older daughters be placed in his care, he would ensure no harm would befall them and suitable marriages be made for them. This is therefore the most likely date for Elizabeth’s departure from the tedious confines of sanctuary at Cheyneygates. She also wrote to Thomas Grey, at that time in France, to return home:

‘By secret messengers she advised the marquise her soon, who was at Parys, to forsake erle Henry and with all speede convenyent to returne into Enland, wher he showld be sure to be caulyd of the king unto highe promotion…’ (3).

Are we really to believe that she left the safety of sanctuary and handed her daughters over to the very man who had murdered their young brothers as well as advise her eldest son to leave the safety of France to return to England ? Really? Still onwards…

3 MARCH 1484. Here enters the story Robert Markenfield. Based in Yorkshire and from a family of high status who first begun their rise under Edward II, Robert was a loyal and trusted follower of Richard III. He was sent by the king southwards to Coldridge in Devon, the confiscated property of Thomas Grey, now in royal hands but on the cusp of being granted to Sir Henry Bodrugan. Coldridge has been variously described as a backwater, difficult to reach and ‘a gritty little village in the boondocks of Devon’ (4). Robert was made keeper of the deer park there. This is fact. The question is why?

‘Robert Markyngfeld/the keping of the park of Holrig in Devonshire during the kinges pleasure…’ Harleian Manuscript 433.

During his time at Coldridge Robert became a friend to Sir John Speke who lived nearby and who would later get himself into trouble for supporting Perkin Warbeck. Incidentally Speke was linked via marriage to Sir James Tyrell, later executed for treason by Henry VII. Tyrell’s wife, Anne Arundel had a niece Alice, who was Speke’s wife. There is a family tradition that Tyrell provided a safe house where Elizabeth Wydeville stayed with some of her children after leaving sanctuary (5). So that is yet another link for you Dear Reader….. Following the Battle of Bosworth in August 1485, Coldridge was returned to Thomas Grey and far as I have been able to ascertain Robert moved to nearby Wembworthy where he lived out the remainder of his life.

We’ve now galloped a little forward in time here and need to backtrack a little:

4 APRIL 1484 but a few weeks after Robert Markingfield’s appointment as Parker at Coldridge, Richard III granted Coldridge as well as a further slew of properties to Sir Henry Bodrugan (6). He was clearly being handsomely awarded by the king as well as having his income increased. Why? A little of Sir Henry’s story should be told at this point. Described as being a ‘lawless and rumbustious individual who was pardoned on at least four occasions between 1467 and 1480. He and his associates seem to have terrorised Cornwall, breaking and entering, engaging in piracy, extracting and misappropriating money under cover of the King’s commission and corrupting wills. His victims complained they could obtain no common law remedy against him ‘for if any person would sue the law against the said Henry … or against any of his servants, anon they would should be murdered, slain and utterly robbed and despoiled of all their goods…’ (7). Nevertheless on a more encouraging note he managed to leave behind him ‘a positive memory in Cornish tradition’ (8). He was clearly one of those larger than life figures prone to often finding himself in hot water – think a medieval Errol Flynn. What’s not to like? With ‘a propensity towards violence‘ – not considered a handicap in those turbulent times – he was inclined to now and again go full tonto (9). He was, nevertheless, popular with both Edward IV and Richard III, being knighted by the former on 18th April 1475 at Westminster on the occasion of his son, the then Prince Edward, being created Prince of Wales, and helping the latter in the Buckingham uprising. It was during the uprising he had tried unsuccessfully to hunt down and capture Sir Richard Edgecombe who managed to escape by the skin of teeth before joining Henry Tudor in Brittany (10). However, for us the most crucial part of Bodrugan’s story is the granting to him by Richard III of none other than Coldridge Manor and Park. Well, well, well. So to summarise at this point, we have Coldridge formerly owned by Thomas Grey, Edward V’s half brother, now owned by one of Richard III’s loyal supporters, Sir Henry Bodrugan, with another of Richard’s supporters. Robert Markenfield, also there in the position of Parker. For some reason the backwater that was Coldridge had become a hotbed of activity.

1485

We now move on to the aftermath of the Battle of Bosworth August 1485. Richard III was dead, Henry Tudor now king and Coldridge Manor and Park back again in the possession of Thomas Grey and his wife Cecilia Bonville. The next question is when Thomas Grey returned from France did he discover his half brother Edward, king for such a short while, ensconced at Coldridge incognito as John Evans? If so it could hardly have come as a surprise as his mother would surely have been informed by Richard III where he was sending Edward or perhaps even the decision had been reached by joint agreement. It was certainly an ideal place with family connections and hidden away. It’s about this time that John Evans first appears out of nowhere as resident at Coldridge where he would in the fullness of time hold the lucrative post of Parker of the deer park. Despite the best efforts of the Missing Princes Project no trace of a John Evans who could be this John Evans has ever been found.

I486

Moving on, Henry, having married Elizabeth of York on 18 January 1486, now had a male heir, Arthur, born in September 1486. Elizabeth Wydeville, now mother of the Queen, had some of her former glory and privileges returned to her. She had also taken out a forty year lease on Cheyneygates, the sumptuous Abbot’s House at Westminster where she had lived with her family during the period of sanctuary. She clearly liked it there – all is rosy! However in February 1487 trouble looms and looms large. Henry had got wind of rebellion…

PRINCE ARTHUR, b 1486. d. 1502. HENRY VII’S HEIR. WAS IT POSSIBLE ELIZABETH WYDEVILLE SOUGHT TO DISINHERIT HER GRANDSON IN ORDER TO REPLACE HIM WITH HER OWN SON, EDWARD V?

1487.

In early February a royal council meeting was held at Sheen – a short time after ‘candell masse‘ – where the rebellion that later became known, quite erroneously, as the Lambert Simnel Rebellion, was discussed. The meeting triggered an immediate tsunami of events beginning with the prompt exit of one of the participants, John de la Pole, Earl of Lincoln, from England to join Francis Viscount Lovell in Flanders. Lincoln’s departure coincided with a slew of arrests, attempted arrests and banishments –

A. Elizabeth Wydeville, Henry’s mother-in-law was sent to live at Bermondsey Abbey. She lost everything she had so recently regained and was never to leave, except for being wheeled out for one or two very rare outings, dying there on the 8th June 1492 and according to her will quite, quite destitute. We can discount her entry into Bermondsey of her own free will as she had recently – on the 10 July 1486 – taken out a 40 year lease on the sumptuous Cheyneygates, the Abbots House at Westminster (11).

B. Thomas Grey, Marquess of Dorset, quelle surprise, was also caught up in the suspicions that were swirling around, and was promptly despatched to the Tower of London, despite his loud protestations of innocence, for the duration of the rebellion. After his release he clearly was never entirely trusted by the wily Henry VII ever again.

C. Bishop Robert Stillington, Bishop of Bath and Wells, the man who it is believed had informed Richard III about Edward IV’s first and legal marriage to Lady Eleanor Butler, was also arrested and imprisoned, never to be released, dying in 1491.

D. Sir Henry Bodrugan and his son John Beaumont became fugitives after Henry VII sent Sir Richard Edgecombe to Bodrugan Barton, their home in Cornwall to arrest them. Both managed to escape by the skin of their teeth. I will return to this matter below.

This chain of events all begs the question why? Why would Elizabeth Wydeville and Thomas risk absolutely everything for the sake of a fake child king or as was rumoured, Edward of Warwick, the young son of George Duke of Clarence, who had been Elizabeth’s enemy? Surely if her sons by Edward IV were indeed dead it would have been more advantageous for Elizabeth to have at least a grandson, Arthur, who would one day sit on the throne rather than rock the boat and have the son of Clarence take the throne? Why on earth would they throw it all away? It makes no sense at all and frankly is the strongest indication that both she and Thomas knew at least one of her young princelings had survived. Could it be they were both fully aware that the young John Evans living at Coldridge was in actual fact Edward V incognito who had been sent there as part of a deal struck between Elizabeth Wydeville and Richard III when she had agreed to leave sanctuary in March 1484? How could they not know seeing that Coldridge had been returned to Thomas?

These links of the story now start to join up –

- The royal council meeting at Sheen where the rebellion was discussed. A French ambassador was also present – probably to wind everyone up……

- The ‘retirement’ of Elizabeth Wydeville to Bermondsey Abbey.

- Thomas Grey, then owner of Coldridge, sent to the Tower of London.

- The arrest of Bishop Robert Stillington.

- Sir Richard Edgecombe being sent to Cornwall to hunt down and arrest Sir Henry Bodrugan, who had only recently been the owner of Coldridge, and his son John Beaumont.

Bodrugan’s Leap. It was from here that Sir Henry Bodrugan made his leap into the sea and into a waiting boat that carried him to safety from Sir Richard’s Edgecombe’s men. He is said to have cursed them as he looked back – all very Errol Flynnish if you ask me…

Now we have reached what is the zenith of the story. Backtracking to February 1487 and following on from the chain of events already mentioned above. Bodrugan and his son Sir John Beaumont were accused of having ‘withdrawn themselves into private places in the counties of Devon and Cornwall and stir up sedition’ (12). What shape could this ‘sedition’ have taken? Bodrugan’s bête noire, Sir Richard Edgecome, who had returned to England with Henry Tudor, was sent to Cornwall to arrest Bodrugan and Beaumont. With his own personal axe to grind how Edgecome must have relished that order! However Bodrugan managed to escape from the back entrance of his house at Bodrugan Barton making his way to nearby cliffs where beneath him a boat awaited. He made one massive leap in the sea and clambered aboard the boat which then carried him to a waiting ship. The place from where he took this leap is known today as Bodrugan’s Leap. Where did he go? What did he do next? This evades us until the next thing we know is that he rocks up in Dublin along with his son John Beaumont and a young lad named Edward. Also arriving soon after are other high status Yorkist rebels including John de la Pole, Earl of Lincoln, Richard III’s nephew, and Francis Viscount Lovell, Richard’s loyal friend from childhood. Margaret the Duchess of Burgundy, sister to Edward IV and Richard III and a thorn in Henry VII’s side, financed the whole enterprise as well as sending Martin Schwartz – a renowned German mercenary and ‘manly manne of warre’ – who brought along 2000 German veterans (13)

The indomitable Margaret Plantagenet, Duchess of Burgundy 1446-1503. Sister to Yorkist kings, Margaret was an persistent and annoying thorn in Henry Tudor’s side and financed the 1487 rebellion. Artist unknown.

The young lad was crowned King Edward in a coronation in Christ Church Cathedral, Dublin on the 24 May 1487. This leads to the question – was this lad actually Edward V who had been living at Bodrugan’s property – Coldridge – incognito as John Evans? Had Bodrugan somehow managed, since evading arrest by Edgecome, to retrieve him from Coldridge and was it he who escorted him to Ireland? Coldridge was now back in the ownership of Thomas Grey and his wife Cecilia Bonville. Did they all – Yorkists diehards – collude together in a joint effort to get a Yorkist king returned to the throne? To clarify it should also be noted that up until this point there is no mention of an even younger boy aged about 10, who went by the name of Lambert Simnel (13). Why? Because Lambert Simnel was a made up name, a Tudor invention – and was never mentioned until later in Lincoln’s Act of Attainder in November 1487 after the Tudor regime had enough time to dream it up. Despite the historian A F Pollard making it perfectly clear that ‘no serious historian has doubted that Lambert Simnel was an imposter ‘ this innocent young ten year old boy is still regularly, up until today, said to have been the lad that was crowned in Dublin. Give Me Strength…

The glorious nave of Christ Church Cathedral, Dublin – scene of the Coronation of the young lad the rebels crowned King Edward – the ‘Dublin King’ .

And so the young Edward had been crowned in a coronation in Christ Church, Dublin. Undeterred by the lack of a crown one was purloined from a nearby statue of the Virgin Mary. Shortly after that the rebels, accompanied by the young newly crowned king, embarked on a journey back to England. There is no indication that Bodrugan was with them. Now aged 61 was he deemed too old or perhaps even too ill to join them. But I wonder did he wave them off as they left on their do or die venture? His son John Beaumont was with them and it must have been a worrying time for him. Finally the terrible news about the outcome of the Battle of Stoke would have reached him. It is not known exactly where or when he died only that it was somewhere in Ireland. Why return to England? His second wife – Margaret, Viscountess Lisle, daughter of William Herbert, Earl of Pembroke who had been executed in 1469 – had predeceased him and now John, his son was also dead.

The Last Stand of Martin Schwartz and his German Mercenaires at the Battle of Stoke Field 16th June 1487. Unknown artist Cassell’s Century Edition of the History of England c.1901.

The rebels, led by Lincoln and Lovell arrived somewhere on the Furness Peninsular around the 5 June. Now here is yet another link. Although the exact landing place is debated where ever it was would have been close to Gleaston Castle (15) Yes! another property owned by Thomas Grey – again having come into his ownership through his marriage and thus via Bonville/Harrington holdings. Could Gleaston, with the kind permission of Thomas obviously, have been a rendezvous point for the rebels who were soon joined by other disgruntled Yorkists wanting to turf Henry VII off his throne and return Edward V to it? In the years following the rebellion Gleaston was abandoned. An in-depth conservation report commissioned by Historic England, and funded by the Castles Studies Trust, suggests that the abandonment may have been down to the civil unrest in the ‘early part of the reign of Henry VII’ as well as the ‘Bonville’s family’s political affiliation with the Yorkist faction during the reign of Edward IV’ which would be a clear indication that Thomas Grey was involved up to his neck in the rebellion. But to return to the rebels. Finally they arrived at Stoke Field where as we know, they were totally defeated – their leaders lost including the brave Martin Schwartz. Among the fallen was John Beaumont, Bodrugan’s son. After the battle the young man who had been crowned King Edward was discovered. We know this because the Heralds reported it:

THE HERALDS REPORT

‘And there was taken the lade that his rebelles called King Edwarde whoos name was in dede John – by a vaylent and a gentil esquire of the kings howse called Robert Bellingham’

Puzzlingly – the Heralds being noted for their precision in identifying folks, and their main raison d’être – omitted to record the surname of ‘John’ or was it later scored out? Why? Well I’ll leave that to you Dear Reader to make your own mind up. Astonishingly this has never been picked up by historians and linked to the Coldridge John Evans although even the strongest doubters must concur it is the most astonishing coincidence. He was taken to Newark, where Henry Tudor, now Henry VII went immediately after the battle, and from that point on he simply disappeared from the annals of history. The Tudors, thinking they were smart, which indeed they were going by the number of folk taken in by it, replaced him with a younger boy, said to be aged about 10, who they named Lambert Simnel – possibly after a cake. I jest of course. And so the biggest question of all – what became of young Edward lately crowned king in Dublin? Is it possible – and I believe it’s highly likely – that Edward was returned to Coldridge to live out his days as John Evans and presumably with the blessing of Henry VII? But why would Henry take the risk of letting Edward live with the danger of further revolts? Of course we can only speculate. In one version of events the French chronicler, Adrien de But, who was not in England at the time, wrote that the young lad – who he called ‘Warwick’ was taken to safety to Guines once the ‘heavy odds again the rebels became known’ . This seems impossible seeing that the Herald noted that the young man was taken after the battle and I only repeat it here in the interest of clarity. Perhaps he was badly injured, maybe even disfigured facially – see point made about this below. Did he himself, after witnessing the deadful carnage at Stoke declare he wanted nothing else other than to just to live peacefully in obscurity? We should also remember that Henry was married to Edward’s sister, Elizabeth of York. Did that also sway him? Did he spare the young lad, his brother-in-law, out of consideration for the feelings of his wife, Elizabeth of York, who Henry is said to have loved. We are after all talking about human beings here not wooden cutouts lacking the most basic of human feelings.

COLDRIDGE

Finally we can now at last focus upon Coldridge and the clues there that have led to the theory that John Evans was Edward V and where he lived out his days as Parker of the deer park. John Evans, after appearing in Coldridge out of nowhere, would marry into the ‘neighbouring local gentry‘ and the Evans family would ‘retain its status throughout the greater part of the sixteenth century’ (16). Today there is no trace of the Evans family in the village. The tradition that John Evans was Edward V incognito (note the clue in the first two letters of the name – Ev = Edward V – plus a Welsh name, Edward being the former Princes of Wales) evolves from various clues in the church which, when tied up to the other links mentioned above, becomes very credible indeed. All this has been covered in my previous posts with their links above. But in a brief resume – we have in the church the wonderful window depicting a young crowned King Edward V. Perhaps that ever loyal Yorkist Cecilia Bonville, who had been widowed in 1501, funded this window which would have been expensive? Above the image of Edward is a large closed crown, which has came from another window, now destroyed, which is very similar to the crowns that can be found over Royal Standards and it’s highly likely that this was its original purpose. In the middle of this crown is a Falcon and Fetterlock, personal badge to Edward IV which is ‘always shown locked in recognition of the line of succession‘ (17) Why all this splendorousness in an inconsequential, hard to reach Devonshire village?

The large closed crown above the image of Edward V and taken from another window. Note the Falcon in Fetterlock Yorkist badge in the middle of the crown and the ermine with 41 deer…

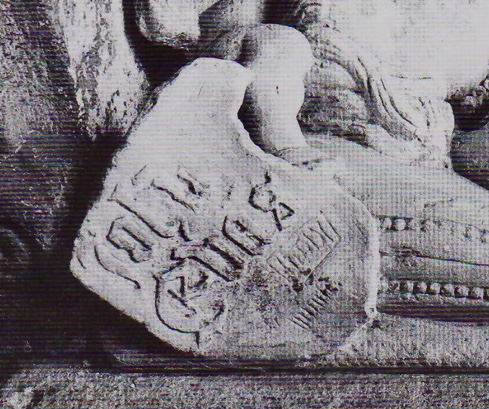

However it was certainly John Evans who founded his chapel there as well as some of the church furniture such as his prie-dieux, now combined into one, as he left us his messages:

‘Pray for John Evans, Parker of Coldridge, maker of this work in the third year of the reign of King Henry VIII’ and ‘Pray for the good estate of John Evans, who caused this to be made at his own expense the second day of August in the year of the Lord 1511’.

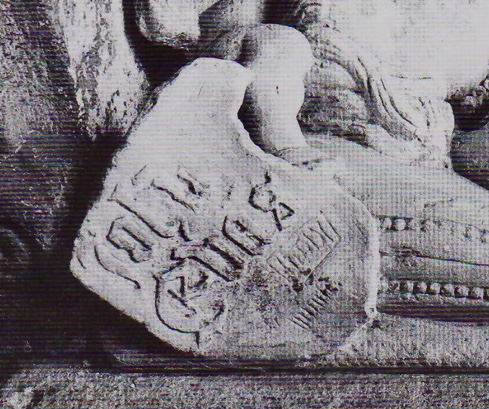

Inside his chapel is his monument, topped with his effigy, his name carved on a shield supported by a roly-poly cherub. The name is spelt as John Eva`s – the letter ‘N’ being missed out although there was more than enough room for it. Was this an intentional message to us: EV = Edward V and Evas which is latin for ‘escape’ and from which the modern word ‘evades’ has evolved from?

There are numerous surviving Yorkist Sunne in Splendour badges dotted about both in glass in the windows and the carved wooden bosses. His effigy lies there looking up at the image of Edward V. Also the face of the adult man, which seems to have been an attempt at a human likeness – all that has survived from another large image in a different window. His face looks uncannily similar to the young face of Edward V. He wears an ermine collar and clutches a crown to his chest. His top lip and chin appears to be disfigured. See my comments above.

The face of the adult man. His top lip and perhaps chin appears to be disfigured. He also wear ermine and part of a crown can be seen. He has chin length hair as does both the image of Edward IV and the face on the effigy.

There are several carvings of ladies in Tudor headdresses vomiting hidden away. But of course the pièce de résistance is the window with the full length image of the young Edward V. Funds are at this very moment being raised to have this extremely rare early 16th century window saved for future generations to enjoy. An informative article on the church written by John Dike leader of the Devon Missing Princes Project can be found here.

The unique and wonderful image of Edward V, St Matthews Church, Coldridge

One of several Sunne in Splendour badges to be found in the church…

FINALE..

It appears to me that perhaps everything that can be discovered/uncovered about John Evans and Coldridge may have now been achieved. Are we now sadly at a dead end? His actual grave and remains are undiscovered and it seems to me that the only way to prove this theory would be their discovery and dna tests. But who knows? I am not an expert on these sort of things – but still – perhaps one day.

Church of St Matthew’s Coldridge under a glowering Devon sky. Possible resting place of Edward V, one of the Missing Princes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to give my heartfelt thanks to the following, some of whom are sadly no longer with us. The information they supplied in their books and articles has helped me immeasurably:

Devon Churchland website; Lambert Simnel and the Battle of Stoke Michael Bennett; The Battle of Stoke; Lambert Simnel Tudor Imposter – Randolph Scott; Lambert Simnel and the King from Dublin, Gordon Smith; Rosemary Horrox and Peter Hammond for their editorship of the priceless Harleian Manuscript; John Ashdown-Hill who delved so deeply into the story of Eleanor Talbot, the Forgotten Queen; South Cumbria Richard III Society group who made me aware of the existence of Gleaston Castle; The Castle Studies Trust who made an in-depth study of Gleaston and linked it to the rebellion of 1487; John Dike, leader and other members of Philippa Langley’s Missing Princes Project in Devon; The Herald who informed us that the young lad that had been crowned King Edward captured after Stoke also had the name of ‘John – ‘; Historian A L Rouse who wrote the excellent article The Turbulent Career of Sir Henry de Bodrugan; Dr James Whetter, author of the History of the Bodrugan family; Chris Brooks and Martin Cherry authors of an in depth article in the Journal of Stained Glass Vol. XXVI which does away with any doubts that it was indeed intended to represent Edward V; and last but not least my good friend Sandra Heath Wilson who has given me unstinting support when I have, at times been about to lose the will to live. If I have left out anybody I do apologise….thank you.

- Kingsford’s Stonor Letters and Papers 1290-1483 p.416. Editor Christine Carpenter.

- revealingrichardiii.com

- Virgil. Quoted in Elizabeth Widville Lady Grey p. 165 John Ashdown-Hill.

- Devon Churchlands website.

- Sir James Tyrell: did some notes on the Austin Friars, London, and those buried there. W. E Hampton

- Harleian Manscript 433 p.124. edited by Rosemary Horrox and P W Hammond.

- Stoke Field, The Last Battle of the Wars of the Roses p.p.25.26 David Baldwin.

- The Turbulent Career of Sir Henry Bodrugan. 1944. A L Rouse

- The Bodrugans – A Study of a Medieval Knightly Family p.141. Dr James Whetter.

- The Turbulent Career of Sir Henry Bodrugan. 1944. A L Rouse

- The Abbot’s House at Westminster. 1911. J Armitage Robinson.

- Cal.Pat.Rolls 1485-94.

- The Heralds Memoir 1486-1490. p.117. Ed.Emma Cavell.

- Lambert Simnel and the Battle of Stoke. Michael Bennett

- Gleaston Castle, Cumbria. Results of aerial survey and conservation statement 2016. Helen Evans and Daniel Ellsworth. Castle Studies Trust.

- Journal of Stained Glass Vol. XXVI. p.28. Chris Brooks and Martin Cherry

- royalmint.com

If you have enjoyed reading this post you might also like:

.

Edward V. St Matthew’s Church, Coldridge, Devon.

Edward V. St Matthew’s Church, Coldridge, Devon.