The Cheapside Hoard. Discovered beneath the floor of an ancient cellar during the demolition of 30-32 Cheapside in 1912. How the owners of such jewels must have shimmered in the candlelight. Photo 1websurfer@Flikr.

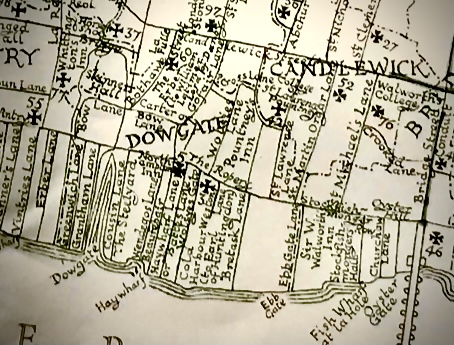

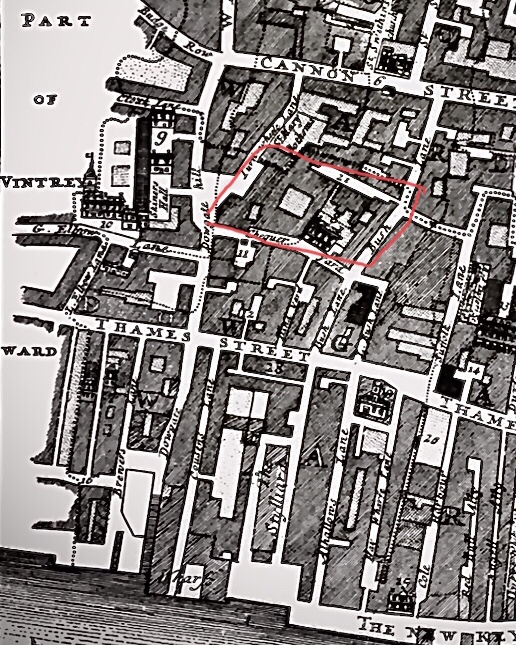

The Cheapside Hoard as it has become known was discovered in June 1912 at 30-32 Cheapside when workmen were demolishing a trio of 17th century post-Great Fire of London houses. The cellars of the original medieval houses destroyed in that fire of 1666 had survived the conflagration and it was somewhere from beneath their floors that the Hoard was recovered. Although the exact spot is now lost to us newspaper reports of the time recorded that the cellar was 16 foot below street level. This would accord with modern archaeological findings which have uncovered other footings and remains of other similar brick lines structures at the same depth. Also unknown is what type of receptacles were used, if any, to bury the Hoard in. I will return to this later but for now let’s take a little look at Cheapside itself. From early medieval times Cheapside was famous for its mercers, goldsmiths and jewellers (the terms jeweller and goldsmith were largely interchangeable in those times and sometimes both terms were applied to the same person in the same documents) who sold their sumptuous wares there. Known as early as 1067 as Westceape (to differentiate it from Eastcheap, the market at the east end of the city) and the Chepe of London in 1257, it was undoubtedly one of the glories of old London, wide enough for a market – from which it first got its name – to be held in the middle of it as well as joustings (1),

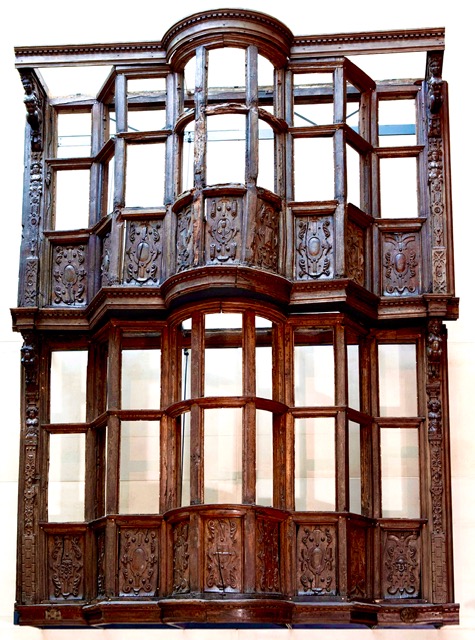

30-32 Cheapside was situated on the corner where it joined Friday Street and was owned by the Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths whose ownership it had been in for centuries. In the 15th century Thomas Wood, a goldsmith who was also a Sheriff of London at one time, had there built a large timber framed structure, four stories high, which he would later give to the Goldsmiths Company in 1491. Comprising of 10 houses and 14 shops, Stow in 1598, was to describe this structure as ‘the most beautiful frame of fair houses and shops in England’. This structure became known as Goldsmiths Row. Later on further houses and shops would spring up along that area of Cheapside which would eventually become generally known as Goldsmiths Row. It was somewhere in this area that our goldsmith plied his trade. Behind the handsome facades would spring up numerous workshops, vaults, countinghouses, gilding chambers, storerooms as well as living accommodation (2). No doubt this led to a lot of coming and goings, old tenants and new tenants etc., Unsurprisingly all was not always harmonious with squabbles breaking out which sometimes caused the Goldsmiths Company itself to get involved and arbitrate. One example is when one tenant, George Lansdale, caused other tenants to complain when he set up a furnace in his cellar which ‘he doth verie dangerouslie mainteyne and work’. It transpired that George had tunnelled through his privy walls to vent the smoke into the street so that noxious fumes wafted through the adjourning properties ‘ to his neighbours great disquiet of mind’. When George refused to remove the furnace he was henceforth hauled off to prison. Another situation which caused great indignation arose when John Hawes took sneaky advantage of his neighbour Edward Wheeler‘s absence in the country to break down the wall between them. He then extended his own property by a few inches but worse still exposed parts of Wheeler’s study ‘wherein were divers writings’ and other personal papers. This was just not on and Officers from the Company inspected the damage. Hawes had to pay Wheeler 20 shillings in reparation (3).

The properties we are interested had five stories with garrets at the top and cellars running beneath them. Over time they had become multi tenanted with rooms divided into smaller rooms and shops so it is now impossible to know which tenant, subtenant or even sub-subtenant was responsible for the burying of the Hoard. It’s all rather mysterious however the most popular theory seems to be that it was buried by our unknown goldsmith prior to making an escape before the Great Fire of London reached the wooden façade of his home and workplace. However as the fire did not wreak its terrible destruction on Cheapside until its third day, Wednesday 5 September, it’s puzzling why our most certainly usually astute goldsmith did not make his escape with his stock well before then. Indeed most of the Cheapside goldsmiths having sufficient warning had already stored their valuables in the Tower of London and ‘thanks to this wise precaution their individual losses were insignificant compared with those of other tradesmen’ (4). Could the burying of the Hoard have occurred in 1665 when the Great Plague cut its deadly swathe across London and Londoners left in droves if able to do so? But this scenario also begs the question why was the valuable stock not taken when the owner made his escape if he indeed did. Was he one of the casualties of that terrible pestilance? Perhaps there was some sort of skulduggery involved. Robbery, even murder? Frustratingly we will never know and presumably the person who buried it died quite soon after having done so.

The Discovery.

George Fabian Lawrence aka Stony Jack in his office at Wandsworth.

Now enters our story – drumroll! – a gentleman by the name of George Fabian Lawrence aka Stony Jack (1862-1939). Mr Lawrence had a multifacited career as a pawnbroker, dealer, collector of antiquities and sometime employee of both the Guildhall and London Museum (5). He had struck up an understanding and rapport with the labourers who were regularly employed in the demolition of the buildings of old London. They became aware that if they handed anything over of interest to him they would be rewarded. Often to be found wandering around building sites Mr Lawrence would later say that “ I got to know a lot of navvies. I thought what a lot of stuff was being lost because they did not know what to look for. I decided to try to teach them. I taught them that every scrap of metal, pottery, glass, or leather that has been lying under London may have a story to tell the archaeologist, and is worth saving. They were apt pupils and hardly a Saturday passed without someone bringing me something. I got 15,000 objects out of the soil of London in 15 years for the London museum alone.’ (6).

In turn the navvies would duly pass on the word that the ‘bloke at Wandsworth who buys old stones and bits of pottery. Got a little shop full of them. He’s a good sport is Stony Jack. If you dig up an old pot or a coin and take it to him, he’ll tell you what it is and buy it off you. And if you take him rubbish, he’ll still give you the price of half a pint’.

Even though accustomed as Mr Lawrence was to navvies bringing him interesting finds he must have thought all his Christmas’ had arrived at once the day the first navvy rocked up at his door bearing a sackful of treasures unearthed from beneath the cellar at 30-32 Cheapside. One of the navvies made the comment ‘We’ve struck a toy shop I thinks guv’nor!‘ when he unloaded his brightly coloured finds still encased in clods of earth. In the following days other navvies would turn up, their pockets or even hats full of treasures until the amount of their finds accumulated to almost 500 pieces – all now piled up in Mr Lawrence’s office. While nearly all the discoveries were taken to Mr Lawrence its clear that a small amount was sold to other purchasers and it was said some navvies disappeared for long periods being able to live off the rewards they had received when they sold their findings elsewhere. Casting that thought aside though and on with story – Mr Lawrence wished to hand on the Hoard to a new and at that time, still unopened museum, which was then taking shape. This was the London Museum. Excited phone calls took place and the Hoard was taken to the home of the Director of the embryonic museum, Mr Lewis Harcourt later Viscount Harcourt, in Berkeley Square. A silence then followed on the Hoard for the next two years until the opening of the London Museum. However, cutting to the chase, following both the British Museum and Victoria and Albert Museum catching wind of the Hoard there then ensued what can only be called an rather unseemly tug of war. To pour oil on troubled waters some items from the hoard were given to the British Museum. This understandably left the Victoria and Albert Museum feeling slightly miffed leading to a flurry of disgruntled memos to the Treasury asking if the treasure had been dealt with in the correct way. i.e. as treasure trove. However by then the Hoard had slipped through the Treasury’s net and would remain where it was i.e the greater part of it in the London Museum. Some 80 items were given to the City Guildhall Museum but in the passage of time both the Guild and the Museum of London were to unite and the bulk of the hoard was once again under the same roof.

The Hoard Itself.

Here is just a small selection from the fabulous treasures in the Hoard.

Scent bottle – enamelled gold, opals, opaline chalcedony, diamonds, rubies and pink sapphires.

Fan handle. Suspension loop to attach to a belt. Photo Museum of London

Fan handle. Suspension loop to attach to a belt. Photo Museum of London

Fan handle: Columbian emeralds and white enamel. Feathers could be held in the flared opening while a loop allowed the fan to be attached to a belt. Museum of London; photo by Robert Weldon/GIA

Gold wirework pendant decorated with enamel and pearls which would be stitched onto the edges of garment. Several of these were included in the hoard.

Two of the numerous buttons in the hoard. This one cloisonné enamel. The one above gold with rubies. Museum of London; photo by Robert Weldon/GIA

Thought to be one of the most valuable items in the Hoare – the emerald cased watch.

Pin with the head in the shape of a ship the hull formed from a large baroque Pearl. Shaft modern.Photo Museum of London.

A pendant of emerald and enamelled gold in the form of a grapevine.

A pendant of emerald and enamelled gold in the form of a grapevine.

The stunning Salamander broach. Columbian emeralds, Indian diamonds and white enamelled legs.

Three examples of the numerous rings in the hoard. The top one with a superb diamond.

A bodkin. One of three in the Hoard. This one gold and turquoise in the shape of a shepherd’s crook. To pin a coil of hair in place. Photo Museum of London.

A bodkin. One of three in the Hoard. This one gold and turquoise in the shape of a shepherd’s crook. To pin a coil of hair in place. Photo Museum of London.

Sapphire Pendant. Possibly for wearing in the hair.

The charming parrot or popinjay cameo. Carved from Columbian emerald. Popinjays, as parrots were then more commonly known. were popular pets since medieval times. Henry VII was known to be particularly fond of them but I digress…

At the time of writing anyone travelling to the Museum of London to view the Hoard will be unlucky as it is not on display for the time being. However a purpose-built gallery for permanent display of the Hoard is planned for the Museum’s new home in West Smithfield which is scheduled to open in 2024.

I have drawn heavily for this post from Hazel Forsyth’s excellent book The Cheapside Hoard, London’s lost Jewels, Museum of London’s informative website and the beautiful photography of Robert Weldon/GIA. Many thanks.

- A London Dictionary of London p.186. Henry A Harben 1912.

- The Cheapside Hoard, London’s Lost Jewels p.22. Hazel Forsyth.

- The Cheapside Hoard: London’s Lost Jewels p.24. Hazel Forsyth.

- The Great Fire of London p.64. Walter G Bell.

- The Cheapside Hoard, London’s Lost Jewels p.45 Hazel Forsyth

- Daily Express 27 June 1928.

If you have enjoyed this post you may also like:

SIR PAUL PINDAR c.1565-1650. AND HIS HOUSE IN BISHOPSGATE

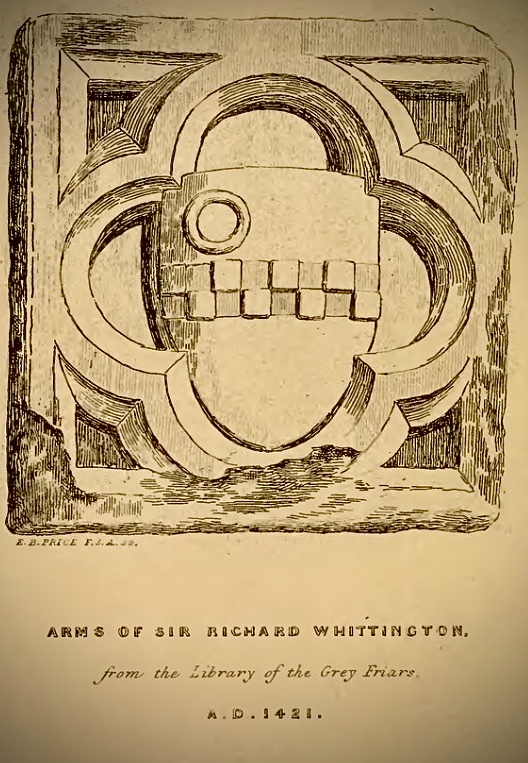

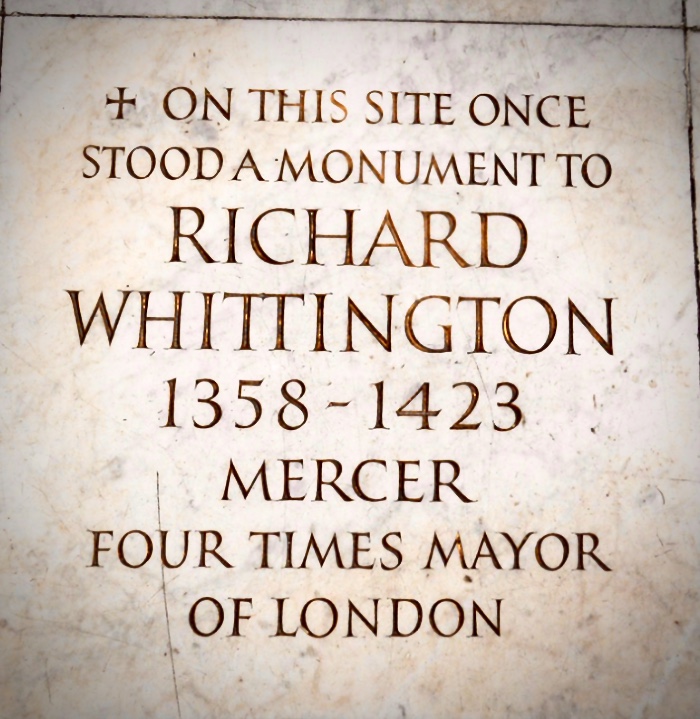

RICHARD WHITTINGTON c.1350-1423. MERCER, MAYOR AND A MOST BENEVOLENT CITIZEN OF LONDON

L’Erber – London Home to Warwick the Kingmaker and George Duke of Clarence

THOMAS CROMWELL’S HOUSE IN AUSTIN FRIARS

THE ORANGE AND LEMON CHURCHES OF OLD LONDON

GREENWICH PALACE – HUMPHREY DUKE OF GLOUCESTER’S PALACE OF PLEAZANCE

![007ZZZ000000008U000080A0[SVC2]](https://sparkypus.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/007zzz000000008u000080a0svc2.jpg?w=582&h=955)