‘So rude a matter and so strange a thinge,

As a boy in Dublin to be made a kinge..’ *

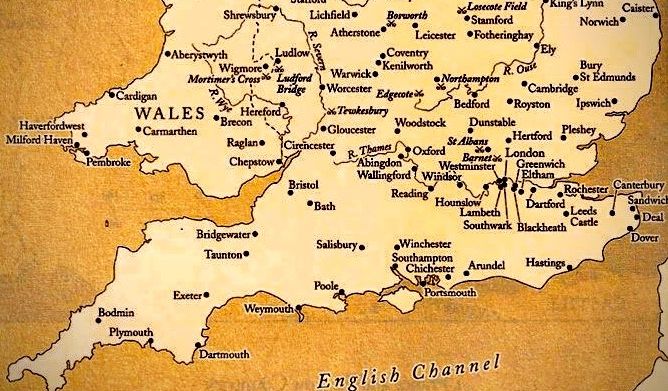

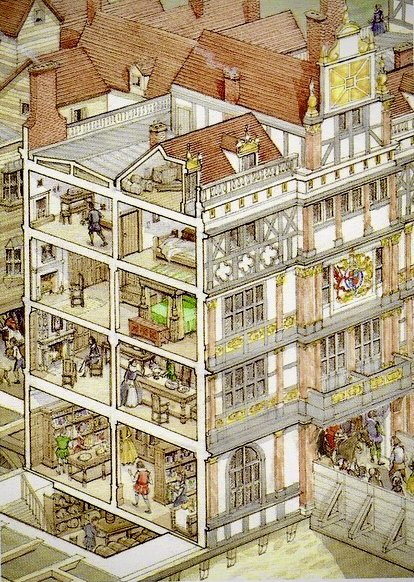

Old St Paul’s where the tragic Edward Earl of Warwick was displayed in February 1487 and with ‘Lambert Simnel’ on the 8 July 1487. ‘Old St Paul’s Cathedral Seen from the East 1656-58’. Artist Wenceslaus Hollar. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

I have gathered much of the information to be found here from the excellent books written by Michael Barrett (very helpful having all the key sources in chronological order in an appendix), David Baldwin (very useful for the battle of Stoke ) and John Ashdown-Hill for candidates for the ‘Dublin King’. Articles by Gordon Smith, Barrie Williams and Randolph Jones were also invaluable.

Main key sources include Molinet, André, Vergil and the Heralds Memoir.

So who was the Dublin King and following on from that who was Lambert Simnel? For the Dublin King we can safely say there were four candidates –

Edward V b. February November 1470, 16 years old in June 1487,

Richard of Shrewsbury b.August 1473, 14 years old in June 1487.

Edward Earl of Warwick b. February 1475, 12 years old in June 1487.

Lambert Simnel described as 10 years old in Lincoln’s Act of Attainder November 1487.

Let us take a closer look at each of them:

Richard of Shrewsbury was very soon passed over (Perkin Warbeck anyone?) which leaves us with Edward V, Edward Earl of Warwick and Lambert Simnel.

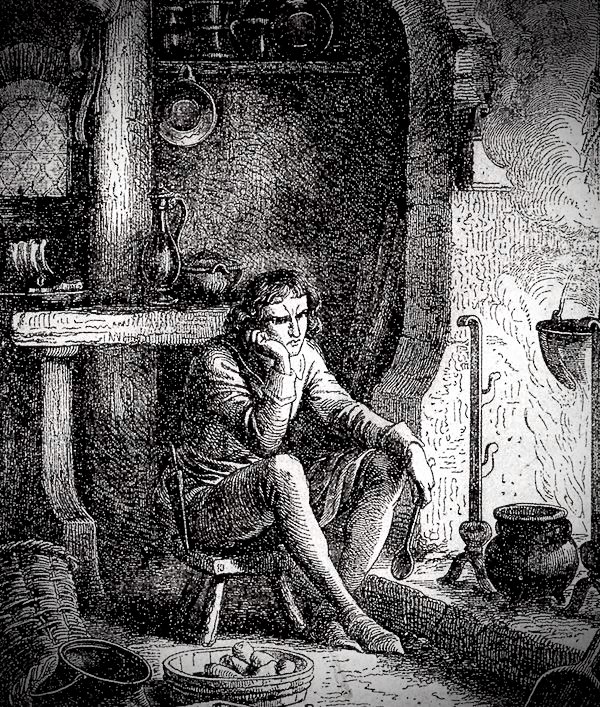

‘Lambert Simnel’ as a scullion in the kitchen of Henry VII. Artist unknown. Getty images.

Despite historian A F Pollard opining that ‘No serious historian has doubted that Lambert Simnel was an imposter’ historians have still doggedly expended large quantities of ink on the probability of whether or not the ten(ish) year old boy known as Lambert Simnel was the young lad who was crowned in Christ Church Cathedral, Dublin on the 24 May 1487.

The next preference seems to have been Edward the young earl of Warwick even though he was, to all intents and purposes, firmly lodged in the Tower of London at the time so he too can be swiftly discounted for that reason alone as well as others which I will return to later. However for some strange reason the chances of the young Dublin king being Edward V have been, on the whole and up until comparatively recently, overlooked which is exactly what the Tudor regime had hoped would happen. It should be remembered that Edward V and his siblings, including Henry’s queen, Elizabeth of York, had all been declared legitimate by Henry’s Parliament in January 1486 and when it got out that a young lad claiming to be Edward V had been crowned in Dublin it opened up a very unpleasant can of worms for Henry. It should be mentioned at this point that there was a strong contender amongst the Yorkists for the suitability of replacing Henry Tudor on the throne as king – Richard III’s nephew, John de la Pole, earl of Lincoln – now one of the leaders of the Yorkist revolt. However the fact that Edward V had recently been legitimised may have focussed Lincoln’s mind to the fact that in the event of the rebellion proving successful it would now have proven difficult for him to make a try for the throne had he so wished. But perhaps loyalty, honour and the knowledge that Edward V had survived never allowed the thought to creep into his thoughts anyway. To muddy already muddy waters further it is unclear whether the boy king was crowned Edward V or Edward VI although this is not of major importance in the scheme of things anyway. The notion that the young lad crowned was either an extremely fake 10 year old or the hapless young earl of Warwick has unfortunately lingered despite it being totally illogical that Lincoln would have thought it a sensible plan to have a counterfeit royal child or even Warwick crowned and anointed – even if Warwick had been the genuine article. This is absolutely baffling and has never been convincingly explained. None of it makes sense until the penny drops that in this case Edward V was the young lad being crowned.

Although evidence is lacking that Richard III either made Lincoln his heir or intended to do so, the fact is that after the death of his son, Edward of Middleham, he appointed Lincoln Lieutenant of Ireland, a post that had been held by Edward and this may indicate the likelihood that he did indeed intend to make Lincoln his heir rather than the much younger Edward earl of Warwick. Richard may have stated his wishes on the matter or even on the eve of Bosworth should things go wrong, which they did. If this was the case. and it seems very likely it could have been, then it would make it highly unlikely that Lincoln would accede to having Edward of Warwick crowned, who was so much younger than him, while knowing that it was he himself Richard had intended as his heir. But of course Edward V would be an entirely different kettle of fish and someone who would easily gain the loyalty of dissident Yorkists. Obviously the truth of the matter went to the grave with Lincoln, which annoyed Henry VII no end, but as way of explanation it has been speculated that Lincoln may have believed he would have been unable to attract enough followers – so to follow that logic through – the suggestion is that he believed the 12 year old son of the attainted George duke of Clarence would? This is absurd. This is put forward despite the glaring fact that he, as a competent adult of the Yorkist royal family with unquestionable and untainted lineage, would surely have been preferable to the young son of Clarence whereas for him to stand aside for a true son of Edward IV makes perfect sense. Suggestions have also been mooted that he may have wanted to rule through a puppet king i.e. young Warwick, or even take the throne from himself in the event the rebellion was successful. Only wait!, wouldn’t he have had a problem with then turfing the young Warwick, now the newly crowned and anointed king, off the throne? Why not just go down the obvious route and go for it himself? However perhaps the most difficult sticking point with Warwick being nominated as Richard’s heir would be that he had no legal claim to the throne because the issue of his father, George Duke Clarence had been barred in an Act of Attainder which was reiterated later in Titulus Regius (The Royal Title) –

‘Moreover we consider howe that aftreward, by the thre estates of this reame assembled in a parliament holden at Westminster the xvijth yere of the regne of the said King Edward the iiijth, he then being in possession of coroune and roiall estate, by an acte made in the same parliament, George Duc of Clarence, brother to the same King Edward now decessed, was convicted and attainted of high treason; and in the same acte is conteigned more at large. Because and by reason whereof all the issue of the said George was and is disabled and barred of all right and clayme that in any wise they might have or challenge by enheritence to the crowne and roiall dignitie of this reame, by the auncien lawe and custome of this same reame …’

To be fair it’s possible Richard could have overturned this just prior to Bosworth and the evidence lost, but how likely would it have been that he would have passed over the capable adult Lincoln in favour of a small boy 10 year old boy. It makes no sense. Surely if the worse came to worse, which it did, he would want a strong hand at the helm to take the House of York safely forward?

A cursory look into Lambert’s story will immediately throw up contradiction after contradiction. For example even the name of the priest, who ‘mentored’ Lambert and therefore a person of importance, is completely muddled being either William Simonds or Richard Simons depending on what version of events you are reading. To get over this awkward anomaly it’s been suggested that William and Richard may have been brothers. At this stage loud warnings bells should be ringing loud and clear. On 17th February 1487 the proceedings of a convocation of Canterbury, held at St Paul’s, were noted by a clerk to John Morton Archbishop of Canterbury. To whit a priest William Simonds, 28 yrs old, confessed to the Big Wigs gathered there that he had ‘abducted and taken across to places in Ireland the son of a certain organ maker, of the university of Oxford, and that this boy was there reputed to be the earl of Warwick’ and that afterwards, Simons himself, was with Lovell in Furness Falls to reconnoitre a suitable place for the Yorkists to land. Yes! – because it makes perfect sense that Lovell would need a priest to aid him in finding the perfect landing spot for the Yorkist army to land. Give Me Strength. Honestly you couldn’t make it up only someone long ago did just that – but still – onwards! Simonds – or was it Simons – was then taken to the Tower of London as Morton was already holding a prisoner, being held for the same offence, at Lambeth and lacked the room for another. Note that neither the boy or his father at this stage had been named.

However according to Vergil – who on the whole is judged to be a good egg – but nevertheless was writing nearly 20 years after the event, ‘Lambert the false boy-king’ was captured along with his mentor, a priest, who had now morphed into Richard Simons, after the battle of Stoke Field. Virgil said this despite the fact that the Herald tasked with recording all the facts in the immediate aftermath of the battle had clearly specified that the rebels had called the young lad King Edward (1). As Barrie Williams points out it should be taken into account Vergil would only have been about 17 when these events were taking place and probably still living in Italy. Therefore his version of events came from ‘Tudor strong partisans’ including Morton – yes him again – More, Foxe, Bray and Urswick. It does not need spelling out yet again the importance for the Tudor regime that it be believed that the Dublin King was a 10 yr old Lambert Simnel, impersonating the 12 year old Earl of Warwick who could be proven to be, beyond doubt, at that very moment in time, incarcerated in the Tower of London. And indeed in the aftermath of Stoke, Lambert Simnel, according to the London Chronicle (recently discovered at the College of Arms) and the hapless young Earl of Warwick were shown openly together at St Paul’s on the 8 July 1487 (2). Still as they say a lie can travel around the world before truth has time to get her shoes on….

Vergil made an interesting blunder with Edward, earl of Warwick’s age, stating that he was 15 years old when he was removed from Sheriff Hutton in 1485 when in fact it would have been Edward, son of Edward IV, who was then aged 15. Interestingly, as Gordon Smith points out, Vergil also pointed out, unhelpfully for the Tudor regime, that the Irish and Germans said that ‘se uenisse ad restituendum in regnum Edwardum puerum nuper in Hybernia coronatum’ i.e. they had come to restore the young Edward crowned in Ireland to the kingdom. As Gordon Smith points out this would rule out young Warwick, who had never been king and thus did not require restoring, but strongly indicates that the Dublin King was indeed Edward V.

In a story found in the Book of Howth some years later, Henry VII invited Irish nobles to a banquet in England where the servant serving them wine was none other than young Lambert, who, in the interim, been despatched to the kitchens. The very nobles who would have been present at the coronation in Dublin failed to recognise the young boy. This is when Henry, who enjoyed a joke as well as the next man, made his famous comment ‘My masters of Ireland you will be crowning apes at length’. Now this is rather confusing. Because if Henry had set out to demonstrate that the young lad crowned in Dublin was the servant serving them, then all he had to do was to sit back and wait for them to recognise him. Which is exactly what did not happen. Shot in the foot much springs to mind. So who was he and from whence did he come, this young Lambert?

The Council Meeting at Sheen and its Aftermath

This meeting held at Sheen, now known as Richmond, in February 1487 concluded with three decisions being made – as well as Lincoln making an immediate exit closely followed by a swift sprint to Flanders :

- The proclamation of a general pardon.

- The exhibition of the ill-starred Warwick

- The immediate removal of Elizabeth Wydeville’s recently won back status, loss of her properties and ‘retirement’ to Bermondsey Abbey. It has been argued by some historians, unconvincingly, that she chose to remove herself there of her own free will. This is despite the fact that she had just taken out a 40 year lease on Cheyneygates, the luxurious Abbot’s house at Westminster Abbey where she had spent time in comfortable sanctuary before sallying out in March 1484 with her daughters in tow having made her peace with Richard III. This event had coincided with Robert Markenfield, a loyal follower of Richard being sent by the king two days later from Yorkshire to Coldridge, Devon, a property that had recently been removed from Elizabeth’s son, Thomas Grey, marquess of Dorset. I will return to that later. Oh! but she was ill some say in explanation. The medieval illness that was serious enough to make someone so poorly as to opt to give up all their worldly possessions and move into closeted Abbey life but where you survived five years has never been specified.

Old and atmospheric photo of the Archway in Abbots’s Court leading out into the cloisters and the outside world. It was through this ancient archway Elizabeth would have led her daughters when they departed the sanctuary of the Abbot’s house at Westminster Abbey. Thomas Grey, marquess of Dorset was also at this time removed to the Tower for the duration of the rebellion all the while expressing his hurt and disbelief that he, of all people, should be held in suspicion! Robert Stillington, Bishop of Bath and Wells, was not so lucky and after his arrest in March 1487, roughly around the time of the council at Sheen, remained in prison for the rest of his life. These facts, taken as a whole, serve to strengthen the belief that Elizabeth et al knew that one or perhaps even both her sons had survived the reign of Richard III. For would she have jeopardised her daughter’s and heirs futures for the son of Clarence, a man who she had loathed and with good reason is believed to be behind his execution and who on reaching adulthood may possibly seek to take revenge for his father’s murder? Interestingly Thomas Grey – who had Coldridge restored to him after Bosworth – would forever more have a close eye kept on him by Henry VII. T B Pugh, who described Dorset as ‘’shifty’ mentions that in June 1492 measures were taken to put the Marquis under restraint through an indenture intended to ensure that he did not commit treason or conceal acts of treason of which others were guilty (3)

Old and atmospheric photo of the Archway in Abbots’s Court leading out into the cloisters and the outside world. It was through this ancient archway Elizabeth would have led her daughters when they departed the sanctuary of the Abbot’s house at Westminster Abbey. Thomas Grey, marquess of Dorset was also at this time removed to the Tower for the duration of the rebellion all the while expressing his hurt and disbelief that he, of all people, should be held in suspicion! Robert Stillington, Bishop of Bath and Wells, was not so lucky and after his arrest in March 1487, roughly around the time of the council at Sheen, remained in prison for the rest of his life. These facts, taken as a whole, serve to strengthen the belief that Elizabeth et al knew that one or perhaps even both her sons had survived the reign of Richard III. For would she have jeopardised her daughter’s and heirs futures for the son of Clarence, a man who she had loathed and with good reason is believed to be behind his execution and who on reaching adulthood may possibly seek to take revenge for his father’s murder? Interestingly Thomas Grey – who had Coldridge restored to him after Bosworth – would forever more have a close eye kept on him by Henry VII. T B Pugh, who described Dorset as ‘’shifty’ mentions that in June 1492 measures were taken to put the Marquis under restraint through an indenture intended to ensure that he did not commit treason or conceal acts of treason of which others were guilty (3)

To return to little Lambert. When was the name Lambert Simnel first bandied about as being the name of the Dublin King? Lambert Simnel was first named in John de la Pole’s Act of Attainder in parliament in November 1487:

‘On the 24th day of May last past at the city of Dublin contrary to his homage and faith, truth and allegiance, traitorously renounced, revoked and disclaimed his own said most natural sovereign liege lord the king, and caused one Lambert Simnel a child of 10 years of age, son to Thomas Simnel, late of Oxford, joiner, to be proclaimed, erected and reputed as king of this realm and to him did faith and homage, to the great dishonour and despite of all this realm’.

This lapse in time between Stoke and Lincoln’s Act of Attainder gave the Tudor regime time to cook up a story to explain away the true, and awkward, identity of the Dublin King.

Prior to the Dublin coronation Henry heard of the rumblings of what was going on in Ireland and according to André he sent a herald to Ireland in an attempt to discover the true identify of the young boy. This herald has been identified as John Yonge, Falcon Pursuivant, by historian Randolph Jones. Yonge was paid £8 with an additional £5 on his return. The trip proved fruitless but it was said that the herald was impressed with ‘Lambert’s’ ability to answer all his probing questions about the court of Edward IV (4). However despite this André still insisted that the young lad was an imposter, although, as Gordon Smith has pointed out, he failed to ‘explain who in Ireland would have had the detailed knowledge of English court life necessary to deceive a herald. The failure of the herald’s trap suggests that the pretender may have been genuine and a detailed knowledge of the times of Edward IV might suggest he was an older boy or young man’ (5) .

LAMBERT SIMNEL’S AGE

This is when it gets really sticky. As Gordon Smith mentions:

‘If the imposter survived the battle of Stoke, a consistent story would need to be told to fill the silence left by the death or disappearance of the conspirators and by the lack of any public investigation. However ‘the narratives of Molinet, André and Vergil suggest there was no such consistency and indeed the new facts about imposter’s name, age and parentage in the Act of Attainder add to the confusion’.

However in light of the fact that both André, who was tutor to Prince Arthur, and Vergil had access to Henry VII’s court where Lambert Simnel had been resident this seems odd. To be fair though André may have been mostly based at Ludlow and not quite in the loop. It seems suspect that there is only one source, Lincoln’s Act of Attainder, where Lambert’s age is given as 10 years old while chroniclers of the time all seem to reach the conclusion he was older and an adolescent.

The late historian John Ashdown-Hill devoted a whole book to the subject – the Dublin King – in which he concluded that it was unlikely that Edward V was he. Loathe as I am to disagree with the findings of such a respected historian who delved far and wide into his research but needs must. Dr Ashdown-Hill, who though of course, as we all are, was unable to ‘prove’ who the Dublin King was he seems to have veered towards it being the Duke of Clarence’s son, Edward. This is on the grounds that Clarence was accused in the Act of Attainder against him, of plotting to get Edward, his then two year old son, out of England and away to safety and it’s possible of course, that he succeeded in this. His book makes many interesting points such as it was written in the Annals of Ulster that ‘a great fleet of Saxons came to Ireland this year (1487) to meet the son (sic grandson) of the Duke of York who was exiled at this time with the Earl of Kildare. And there lived not of the race of the blood royal that time but that son of the Duke and he was proclaimed king on the Sunday of the Holy Ghost (third of June) in the town of Ath Cliath (Dublin). Alas Dr Ashdown-Hill did not make a connection to the possibility of this grandson being the oldest grandson of the Duke of York.

So in summary Lambert Simnel being the young boy that was crowned in Dublin and who was then taken after Stoke is so extremely unlikely as to be non existent as well as daft. After looking at it as far as I can go, I now believe that Lambert Simnel was never at Dublin leave alone crowned and annointed king in Christ Church Cathedral. I think he was substituted in the aftermath of Stoke with the ‘lad that his rebels called King Edward whose name was indeed John‘ (6). As Gordon Smith puts so succulently ‘ The changes between Simons confession in February and Lincoln’s Attainder of November 1487 tend to confirm that the character of Lambert Simnel emerged at the end of an ad hoc story invented by the English government in response to the events of the 1487 rebellion. Virgil’s narrative transposed Lambert back to the start of the conspiracy and to this transposition can be attributed Virgil’s mistakes (e.g. Warwick’s age … and the capture of Simons) and the implausibility of the pseudo-Warwick plot. … the conclusion that the king from Dublin was Edward V not only fits the events of the so-called Simnel rebellion of 1487 but also explains the differences in the narratives of Molinet, André and Virgil There are reasons to believe that the ‘John’ who was captured after Stoke was John Evans who indeed was Edward V and who had been living incognito in Coldridge, Devon, the property of his half brother, the Marquess of Dorset with the knowledge of Richard III. It should be remembered that on the 3rd March Richard had despatched one of his trusted followers, Robert Markynfield – ‘Robert Markyngfeld/the keping of the park of Holrig in Devoneshire during the kinges pleasure..’ – to Coldridge two days after Elizabeth Wydeville left sanctuary on the 1st March 1484, where he would remain until after Bosworth (7). Furthermore is it possible that Richard on the eve of Bosworth had asked Lincoln, in the event of the battle going badly, to aid his younger cousin when the time was right to regain his throne? Richard would have known this would have appealed to the dissident Yorkists who had never quite accepted the removal of Edward IV’s son from the throne. Did Richard reason that if he were to lose his life in the ensuing battle that an illigitimate son of Edward IV would be very much preferable to the alternative. With guidance from Lincoln perhaps all would be well and the White Rose of York bloom once more. This could be an explanation of why Lincoln gave the Dublin King, who I believe was Edward V, his complete support in the venture to try to regain his throne. Tragically Lincoln was to die in the attempt and as ‘John’ disappeared after Stoke there is good reason to believe that he may have been returned to Coldridge to live out his life incognito.

The Last Stand of Martin Schwartz and his German Mercenaries at the Battle of Stoke Field 16th June 1487. Unknown artist Cassell’s Century Edition History of England c.1901.

We should also add to the equation Sir Henry’s Bodrugan’s important role in the story of Coldridge, which he owned, Richard III having given it to him, and his presence at the Dublin Coronation. But that is another story and if you are interested you can read it here.

The adults who arranged the switch and presented the 10 year old boy who had been hastily renamed Lambert Simnel would have known, one would like to believe, that under the circumstances, the young and innocent boy would not be severely punished even if at all. In fact Lambert was given a safe if unexciting job in the royal kitchen although later he would rise to the giddy heights of falconer. I wonder could he have been the son or a young family member of an accommodating servant who could have been bribed and convinced that if the young boy went along with the story and new identify he would be found a safe position in the kitchens and perhaps even get promotion. Which he did. What’s not to like? Is there any record of what became of Lambert? Vergil wrote that he was still alive ‘to this very day‘ when writing c.1513. Michael Bennett wrote that he was issued with robes for the funeral of Sir Thomas Lovell, a courtier and counsellor of Henry VII in 1525. After that he fades away into the mists of time.

* From an old Irish song. With thanks to Randolph Scott.

- Heralds Memoir.

- Lambert Simnel’s Rebellion: How reliable is Polydore Vergil? Barrie Williams.

- Grey, Thomas, first marquess of Dorset c.1455-1501. T.B. Pugh. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography 2004.

- The Extraordinary Reign of ‘Edward VI’ in Ireland 1487-8. Ricardian Bulletin March 2021

- Lambert Simnel and the King from Dublin. Gordon Smith.

- Heralds Memoir.

- Harleian Manuscript 433 p.140 Vol One

If you have enjoyed this article you may also like

A Portrait of Edward V and Perhaps Even a Resting Place?- St Matthew’s Church Coldridge

A PORTRAIT OF EDWARD V AND THE MYSTERY OF COLDRIDGE CHURCH…Part II A Guest Post by John Dike.

Edward Earl of Warwick – His Life and Death.

The Mysterious Dublin King and Battle of Stoke

PERKIN WARBECK AND THE ASSAULTS ON THE GATES OF EXETER

Lady Katherine Gordon – Wife to Perkin Warbeck

AUSTIN FRIARS: LAST RESTING PLACE OF PERKIN WARBECK

Cheyneygates, Westminster Abbey, Elizabeth Woodville’s Pied-à-terre

SIR HENRY BODRUGAN – A LINK TO RICHARD III, EDWARD V, COLDRIDGE AND THE DUBLIN KING