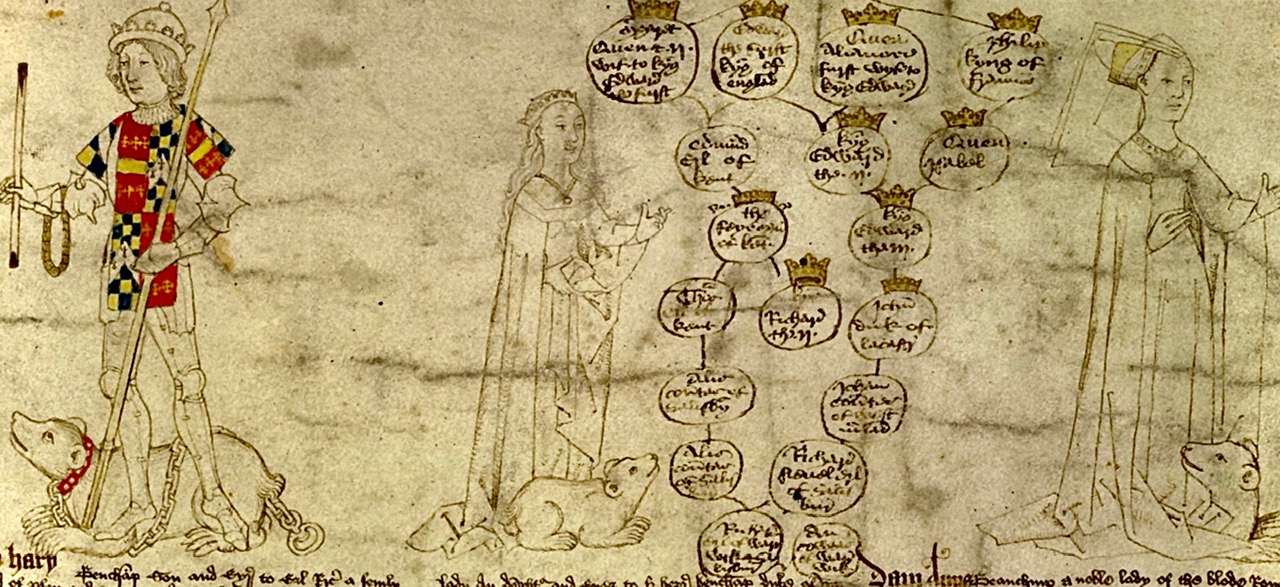

Anne Beauchamp and her husband, Richard Neville ‘The Kingmaker’ Earl of Warwick. From the Latin version of the Rous Roll. Donated to the College of Arms by Melvyn Jeremiah.

Anne Beauchamp (1426–1492), Countess of Warwick, daughter of Richard Beauchamp, 13th Earl of Warwick (1382–1439) and his second wife Isobel Despenser (died 27 December 1439) was born at Caversham, Oxfordshire in 1426. She was sister and heir to Henry, Duke of Warwick and wife to Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick later known as ‘The Kingmaker’ (1428–1471). Anne was one of that distinguished band of ladies who suffered in varying degrees during the tumultuous times known as the Wars of the Roses mostly due to the propensity of their menfolk spending a large part of their time charging up and down the country trying to knock each others blocks off.

Anne and Richard would have two daughters who themselves made illustrious marriages, Isobel the eldest, to George, Duke of Clarence and Anne who would become a Queen, wife to Richard III. But let’s not gallop too far ahead in Anne’s story. To start back at the beginning – in 1434 Anne’s father Richard Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick along with Richard Neville, Earl of Salisbury ((1400–1460) would arrange the marriages of their daughters and sons when they were but young children. The eight year old Anne Beauchamp would marry the six year old Richard Neville, while Richard’s sister, Cecily (d. 1450) would marry Henry Beauchamp (1425–1446) Anne’s brother. Naturally, of the two marriages the one between Henry and Cicely was the most important. A double wedding was celebrated at Abergavenny, Wales on or about 4 May 1436. Salisbury would pay a hefty dowry for Cecily of 4,700 marks which equated to about £3,233 13s 4d (1). Prima facie this did not appear to be the most advantageous marriage for Richard, for it was his child bride’s brother, Henry, who would inherit the vast Warwick and Despenser estates and of course the earldom (2). However fate took a hand with the early deaths of Henry in 1446 shortly followed by the death of his sole heir, Anne, his five year old daughter in 1449. This little girl who died at Ewelme, Oxfordshire, would be buried before the high altar at Reading Abbey besides her great grandmother, Constance (3). Anne, being Henry’s sole whole sister and thus his heir, inherited the Beauchamp estates as well as being a coheiress with another sister and also entitled to a half-share of their mother’s Despenser estates. According to historian Michael Hicks, Warwick acquired the other half by the simple expedient of securing the custody during the minority of the coheir, George Neville of Abergavenny, and refusing to relinquish it on his majority (4).

This caused quite a furore with Henry and Anne’s three half sisters from their father’s first marriage to Elizabeth Berkeley (c.1386-1422). However this was to no avail despite two of these sisters having influential husbands: Margaret, married to John Talbot, first earl of Shrewsbury; Eleanor, married to Edmund Beaufort, first duke of Somerset and Elizabeth, married to George Neville, Lord Latimer. The die was cast legally and the young couple were now Earl of Warwick jure uxoris/by right of his wife and Countess of Warwick, suo jure/in her own right. Richard and Anne were now an extremely wealthy couple and this wealth was further increased when, upon the death of his mother Alice Montague in 1462, Richard inherited her Salisbury inheritance

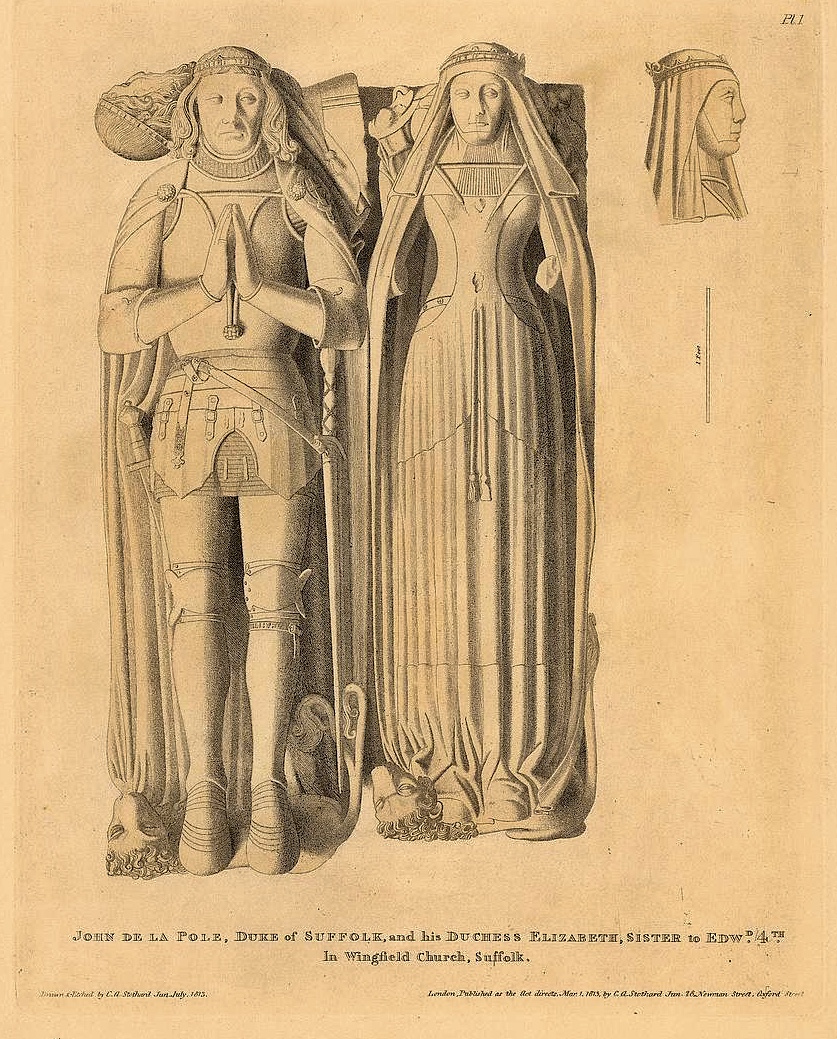

Henry, Earl of Warwick, his daughter Anne, and sister Anne who would after their deaths become Countess of Warwick. Rous Roll.

John Rous, antiquarian and chantry priest of Warwick, wrote glowingly of the Countess, as he did for all the Earls of Warwick and their families – clearly for Rous ‘there is no such thing as a bad earl of Warwick’ (5).

Anne Beauchamp. Latin version of the Rous Roll. Unmuzzled bear at her feet. Photo the Heraldry Society.

‘Dam Anne Beauchamp a noble lady of the blode royal dowhter to Eorl Rychard and hole sustre and eyr to fir herre Beauchamp duke of Warrwik and aftre the deffese of his only begoten dowhtre Lady An. by trew enheritans countas of Warrewick which goode lady had in her dayes grete tribulacon for her lordis fake Syre Rychard Neeuel fon and Eyre to fir Rychard Eorl of Salifbury and by her tityll Eorl of Warrwik a famus knyghe and excellent gretly fpoke of thorow thr mofte part of all chrifendam. This gode lady was born in the manor of Cawerfham by redyng in the counte of oxenforde and was euer a full deuout lady in Goddis feruys fre of her fpeche to euery perfon familier accordyng to her and thore degre. Glad to be at and with women that traueld of chyld. full comfortable and plenteus then of all thyng that shuld be helpyng to hen. and in hyr tribulacons fhe was euer to the gret pleafure of God full pacient. to the grete meryte of her own fowl and enfample of all odre that were vexid with eny aduerfyte. Sho was alfo gladly euer companable and liberal an in her own perfone femly and bewteus and to all that drew to her ladifhup as the dede fhewid ful gode and gracious. her refon was and euer fhall.

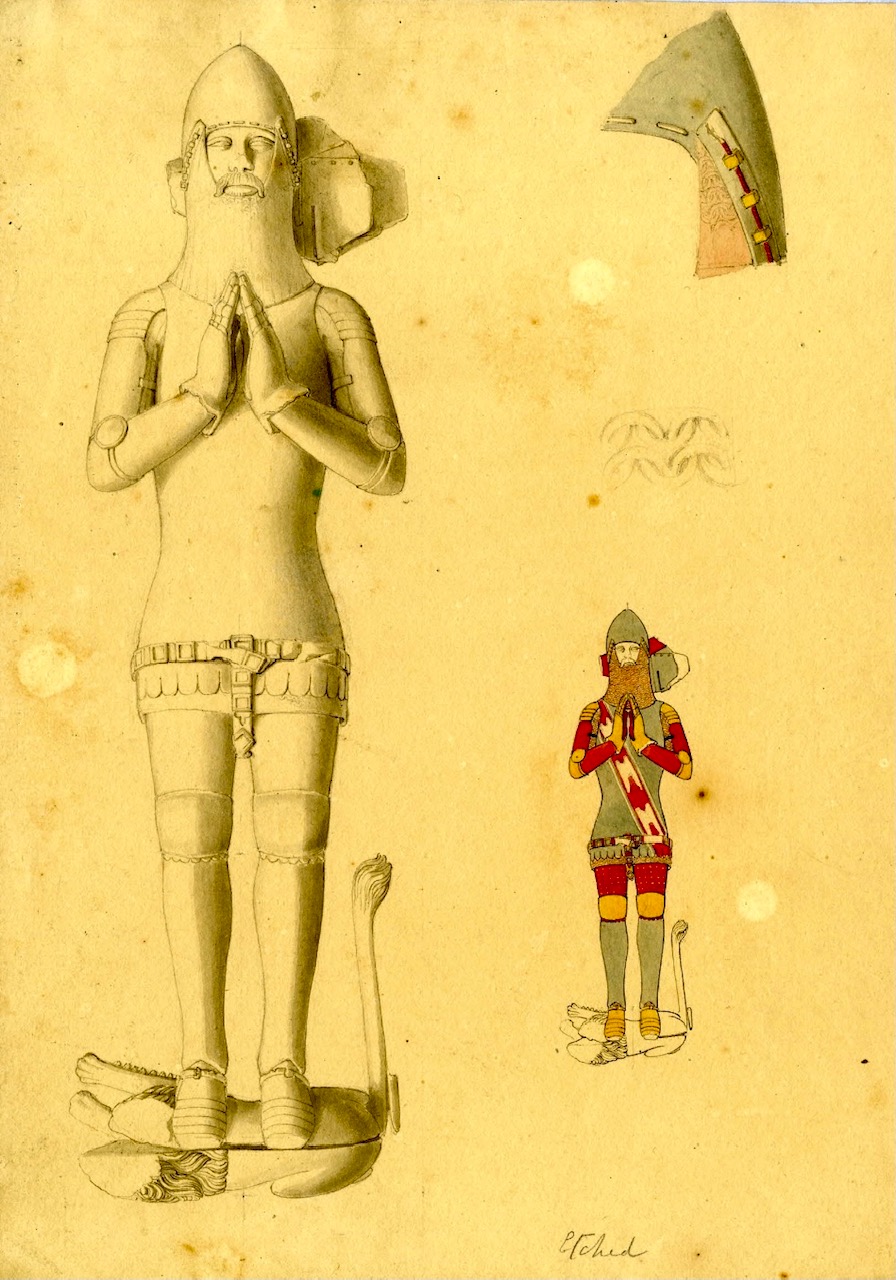

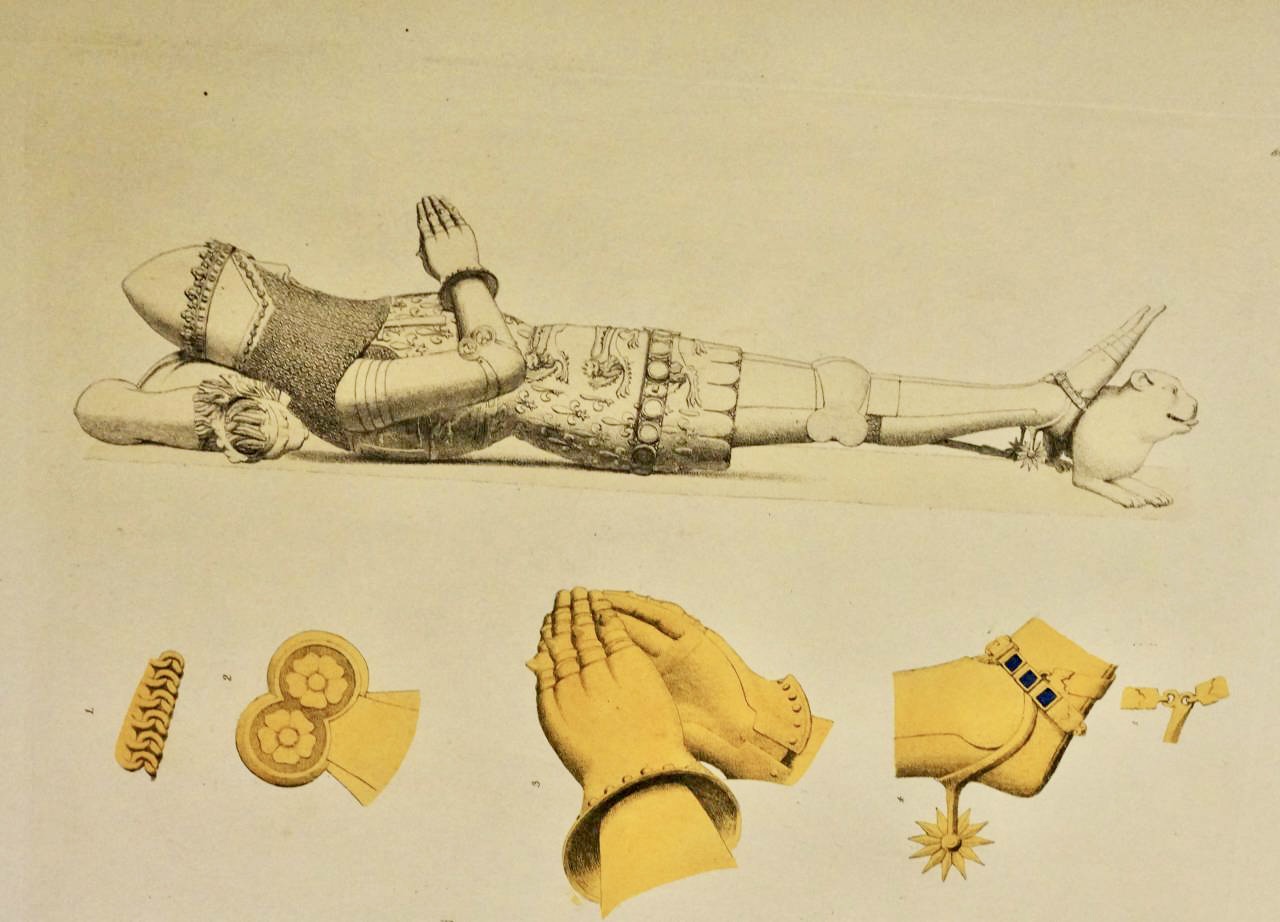

Anne’s father, Richard Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick. Bronze effigy in the Beauchamp Chapel, Collegiate Church of St Mary, Warwick. This wonderful effigy is the work of William Austen. Photo Aiden McRae Thomson.

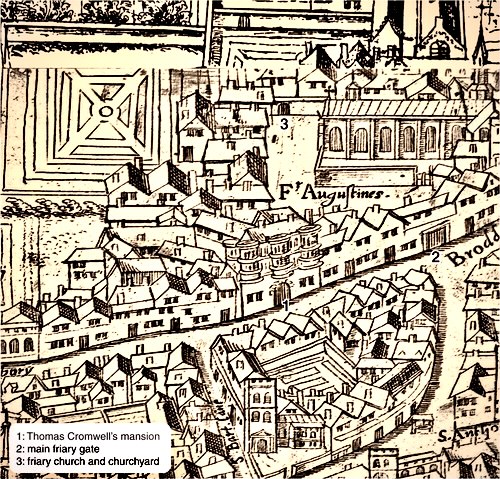

So we have seen by 1449 Anne and Richard were now Countess and Earl of Warwick, their main home being Warwick Castle, but also spending time at Middleham and Sheriff Hutton as well as a great London house, The Erber, where food would be given to the crowds of poor people who would gather at the gate every day. Stow tells us that ‘were oftentimes six oxen eaten at a breakfast and every tavern was full of his meat; for he that had any acquaintance in that house might have there so much of sodden and roast meat as he could prick and carry upon a long dagger’ (7).

Warwick Castle. Main home to Anne Beauchamp and Richard Neville, earl of Warwick. Photo with thanks to Scotty Rae @Flkr.

All may have been progressing swimmingly well but by 1450 there were warning signs that the feuds and disgruntlements involving Warwick’s uncle by marriage, Richard Duke of York (1411–1460) and the Lancastrian royal party were beginning to take a turn for the worse. York had returned from Ireland and demanded, justifiably, a reform of the Government. Things were to rumble on until coming to a head in 1455. The turbulent period later to be known as the Wars of the Roses took off. I will not go too deeply here into the twists, turns, battles, victories and defeats that occurred in the years that were to follow for this is, after all, about Anne and those events are well set out elsewhere. Should anyone want to find out more about the Kingmaker I can recommend the biographies on him by Paul Murray Kendall and A J Pollard. In brief summary as Kendall noted succinctly in his biography, Warwick had arrived at where he was by ‘consequence of the family into which he was born, the marriage his father made for him, and the time of violence in which he was bred’. Warwick would labour hard and long for the house of York until events triggered by Richard Duke of York’s son, now Edward IV, culminated in a once unthinkable turnaround – he would throw in his lot with the Lancastrians, then led by possibly his greatest nemesis, Margaret of Anjou. This now unstoppable chain of events culminated in Warwick’s death, aged 42, on a foggy day at Barnet on Sunday 14 April 1471. .

But back to Anne. She does appear to be rather an elusive character but one of the facts that is known about her is that about 1465 she took into her household at Middleham the young Richard Duke of Gloucester. Richard was the youngest brother of the new king, Edward IV, who her husband had been instrumental in setting upon the throne. The young Gloucester stayed there for approximately three years to learn with his henchmen the art of war as well as the more refined arts of manners, conversational skills and so forth. It is possible that an affection grew between Richard and Anne Beauchamp as she took the place of his mother during those formative years. This domestic situation came to a swift end when the relationship between her husband and Edward IV soured. Things went from bad to worse when in Calais in July 1469, her eldest daughter Isobel was married to Edward’s brother, George Duke of Clarence against the explicit wishes of the king.

Return to England would find Anne with her daughters at Warwick Castle while Warwick and Clarence became embroiled in open rebellion. Proclaimed traitors and with a price upon their heads they were forced to flee but not before a diversion to Warwick castle where after gathering their womenfolk together, including a now eight month pregnant Isobel, they made their escape, their intended haven being Calais. Now I know the ladies of that time had backbones of iron but that journey must have been the very stuff of nightmares for Anne and her daughters. Isobel went into labour while they were at sea having been refused entry into Calais. Despite wine being sent to them to ease Isobel’s pains by a sympathetic Lord Wenlock, the very least he could do under the circumstances, Isobel and George’s baby was born dead or died shortly after birth. What a dreadful day when that little body was buried at sea. Finally the bedraggled party arrived in Honfleur where they were received by representatives of King Louis who tried to intercede for them with Margaret of Anjou, their old enemy. This led to an extraordinary deal being struck between Warwick and Margaret of Anjou, that ‘great and strong laboured woman…’ (7). Anne’s youngest daughter, Anne Neville, was betrothed to Margaret’s son, Edward of Lancaster, in a move which reneged on Warwick’s pledge to make George and Isobel king and queen. You can see where this is heading Dear Reader…. Following on from this astonishing volte-face, unfortunately no one knows what words were exchanged in private between parents, daughters and particularly the disgruntled son-in-law but it couldn’t have been pretty. George would have, understandably, been mightily hacked off to say the very least, which would lead to his eventual desertion of his father-in-law and return to the Yorkist fold. What Anne’s thoughts were on these events – did she question her husband’s judgement or did she back him in this startling change of plans – we will never know. Warwick and Anne bid farewell to each other for what was to be the last time when he set out on his journey back to England. Engaging with Edward IV’s army at Barnet on the 14 April 1471 left both Warwick and his brother John Marquess of Montague, with his divided loyalties, dead. Anne was to hear about her husband’s death when she landed somewhere on the southern coast, possibly Weymouth, the same day of the battle. She immediately headed for Beaulieu Abbey, Hampshire and sanctuary where she was to remain until the summer of 1472. Three weeks after her arrival at Beaulieu, her new son-in-law, Edward of Lancaster, was to die at Tewkesbury, his mother captured and later returned to France a broken woman.

In the outside world a battle supreme was to take place over Anne’s inheritances between her two royal son-in-laws, George Duke of Clarence and Richard Duke of Gloucester who had in the interim married the now widowed Anne Neville. Anne would complain and send out letters to anyone she thought might aid her in her battle to get some restitution of what should have been rightfully hers. But now, deemed the wife of a traitor, she was, as the saying goes, up the Swanee without a paddle and all her protestations were to fall on deaf ears. Her lands were divvied up ‘as yf the seid Countes were nowe naturally dede’. When it had all been done and the dust settled, Richard and Anne would send a trustworthy Sir James Tyrell to Beaulieu to bring Anne home to Middleham much to the chagrin of George who was informing anyone who would listen that he was going to ‘dele with’ his brother. As it transpired, it was George who was dealt with but that is another story. And there in Middleham Anne gently faded into the mists of time. Rous was to write that Richard and/or Anne held her as a prisoner and locked up. This rather lurid tale we can confidently discount as he also wrote that Richard had been two years in his mother’s womb and was born with a full set of teeth.

There is every reason to believe that Anne spent those latter years in well deserved peace, tranquillity and a very comfortable lifestyle. It’s recorded that a servant, William Catour, were sent to do shopping for her in York which would indicate that she was once more living a privileged lifestyle (8). It is also very likely that she was behind the creation of the Beauchamp Pageant, a beautiful pictorial history of the life of her father, Richard Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick. The Pageant consists of 53 drawings accompanied by explanatory text and is dated to having been made around 1483, the year that her daughter Anne Neville became queen (9). Anne’s life was to take one last final turn in 1485 with the death of her son-in-law, Richard III at Bosworth leaving her destitute. She had by then lost her husband, two daughters, two son-in-laws and a grandson. Fortunately she did not live long enough to see the execution of her two Clarence grandchildren, Edward and Margaret. However she reached some sort of agreement with the new king, Henry Tudor, who granted her a yearly pension of 500 marks and returned some of her lands to her on the basis that when she died, they would revert back to the crown. Anne was thus able to live out the remainder of her life in reasonable wealth and comfort. Although of course the glory days were over so too were the days of angst, fear and extreme stress although perhaps tears may have flowed from time to time as she must have recalled the grievous losses she had sustained over the years. Perhaps she gained some comfort when she perused the ‘Pageant’ and was reminded once again of the exploits of her illustrious father. Anne was to die in 1492. It’s unknown where she was buried but as she is believed to have died at Sutton Manor, Warwickshire and so may be buried in the parish church of that place (10).

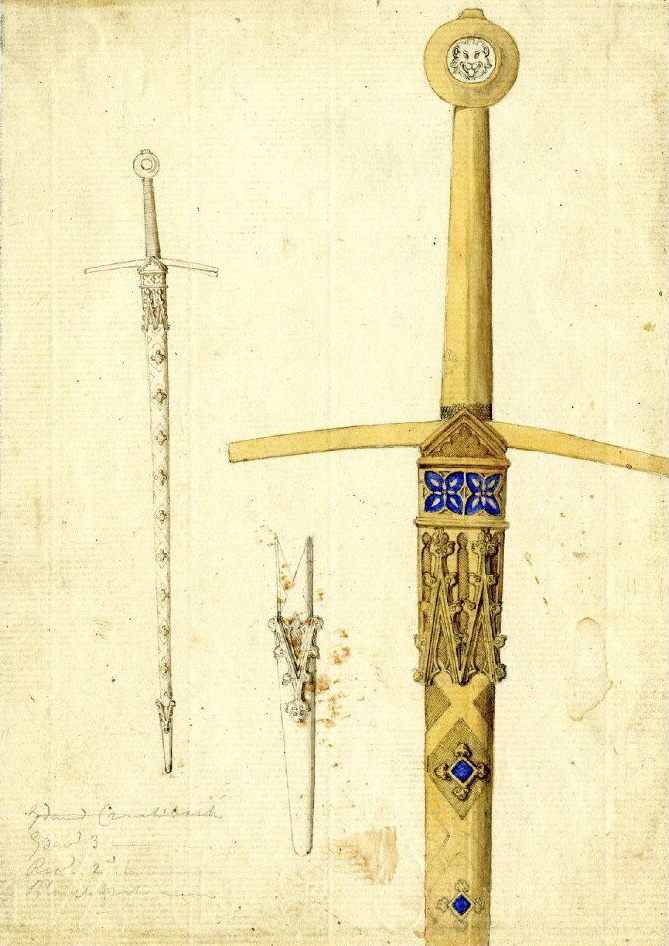

Below just a few of the beautiful drawings from the Beauchamp Pageant. All of them and full text can be found in The Beauchamp Pageant Edited by Alexandra Sinclair. A sumptuous book and fully recommended.

Here the earl kneels before King Henry receiving a letter appointing him Captain of Calais.

Here can be seen Anne’s parents, Earl Richard and Isobel Despenser as well as her brother, twelve year old Henry, lashed to a mast during a great storm. They pray for deliverance as does a sailor. The Earl has donned a blazoned surcote which would ensure their identification should the worse come to the worst…

A joust between the Earl and Sir Colard Fynes. The earl is shown re-mounting his horse after dismounting to prove he was not tied on…

The Earl’s burial in the Beauchamp Chapel, St Mary’s Collegiate Church, Warwick.

A family tree from the Pageant. Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick is shown at the top with his wives beside him, Elizabeth Berkeley and Isobel Despenser. Three branches at the bottom left show the three daughters the earl had by Elizabeth and the two branches to the right depict Henry and Anne, his children by Isobel.

- Anne Neville Queen to Richard III p. 37. Michael Hicks.

- Warwick the Kingmaker, p.19. Paul Murrey Kendall.

- The Rous Roll By John Rous. Introduction by William Courthope. Printed for William Pickering 1845

- The Warwick Inheritance Springboard to the Throne. Michael Hicks. Ricardian Bulletin June 1983.

- The Rous Roll p.xv. By John Rous. Introduction by William Courthope. Printed for William Pickering 1845.

- A Survey of London Written in the year 1598 p.92. John Stow.

- Paston Letters, I.p.377.

- Testamenta Eboracensia vol 3 p.3.

- The Beauchamp Pageant, Edited by Alexandra Sinclair. Reprinted in 2002. I have found this the most useful source of information for the life of Anne Beauchamp available

- ‘Of lordis lyne & lynge sche was’ Ricardian Vol.XXX 2020 p.24. Anne F Sutton and Livia Visser-Fuchs.

If you enjoyed this post you might also like :

EDWARD, EARL OF WARWICK – HIS LIFE AND DEATH

Margaret Pole Countess of Salisbury 1473-1541 Loyalty Lineage and Leadership by Hazel Pierce.

THE CHILDREN OF JOHN NEVILLE, MARQUIS OF MONTAGU and EARL OF NORTHUMBERLAND d.1471

GEORGE DUKE OF CLARENCE, ISOBEL NEVILLE AND THE CLARENCE VAULT

,

,