Elizabeth Wydeville The Royal Window Canterbury Cathedral.

Elizabeth Wydeville The Royal Window Canterbury Cathedral.

Yes, the title of this post is a serious question. Although prima facie it may appear absurd, after all we are talking about a real actual Queen, not a monster from a Grimms’ fairy story, I think it may be worthwhile to give some actual consideration to this question and its plausibility.

Edward IV, the Royal Window Canterbury Cathedral. Did a careless remark made to his wife unwittingly bring about the death of the earl of Desmond?

Lets take a look at the first death that Elizabeth has been associated with – that of Thomas Fitzgerald Earl of Desmond. The first port of call for anyone interested in this would be the excellent in-depth article co-written by Annette Carson and the late historian John Ashdown-Hill both of whom were heavily involved with the discovery of King Richard III’s remains in Leicester. Here is the article.

Their assessment goes very deep but to give a brief summary – Desmond was executed on the 15th February 1468 by his successor, John Tiptoft, Earl of Worcester, a man known for his cruel, sadistic nature and dubbed The Butcher of England by his contemporaries. The execution was immediately followed by armed rebellion – the Earl’s elder sons ‘raised their standards and drew their swords to avenge their father’s murder ‘ – which was swiftly followed by King Edward, both alarmed and displeased in equal measures, promising that if the Desmonds laid their arms down they would be pardoned. Edward also assured them that he had neither ordered the execution or had any knowledge of it whatsoever. This begs the question if it was not Edward who gave Tiptoft the go ahead to execute Desmond – as well as, it is said, his two small sons – then who was it? This was swiftly followed by extremely generous grants to James, Desmond’s oldest son, despite the Act of Attainder against his father. Included in these grants was ‘the palatinate of Kerry, together with the town and castle of Dungarvan. This grant may be thought to signify that in Edward’s view an injustice had been done’. This was as well as an ‘extraordinary priviledge’ Agreement was also reached that Desmonds were free to choose not to appear in person before Edward’s deputy or the council in Ireland but to be able to send a representative instead. Clearly Edward had grasped that the Desmonds were, understandably, extremely wary of putting themselves in the hands of the Anglo Irish authorities.

Richard Duke of York. His wise and just reputation in Ireland survived long after his death.

Various explanations have been given as to why Tiptoft had Desmond executed. It was given out that he had been guilty of ‘horrible treasons and felonies as well as alliance, fosterage and alterage with enemies of the king, as in giving them harness and armour and supporting them against the faithful subjects of the king‘ as well as the ludicrous charge of plotting to make himself King of Ireland,

Upon Tiptoft’s arrival in Ireland in September 1467 he had initially co-operated with Desmond and other Irish lords. This was unsurprising as Edward IV was on extremely friendly terms with the Irish lords. This friendship had carried over from his father, Richard, Duke of York’s time in Ireland where he had been held in high regard and in fact Desmond’s father, James, had been George Duke of Clarence’s godfather. However on the opening of Parliament on the 4th February a bill was immediately brought forward attainting Desmond and others including his brother in law, the Earl of Kildare. Desmond was removed from the Dominican friary at Drogheda on the 14th February and swiftly executed. The others managed somehow to avoid arrest and execution until Edward, finding out what had occurred, pardoned them. This also adds to the strength of the theory that the execution had been carried out without Edward’s knowledge. This might be a good point to mention that Desmond had indeed been in England around the time of Edward’s ‘marriage’ to Elizabeth and when much chatter was going on regarding her unsuitability as a royal bride. There is a surviving 16th century account of Edward, while having an amicable chat with Desmond, asked him what his thoughts were regarding Edward’s choice of bride. It is said that Desmond at first wisely held back but pushed by Edward did admit that it was thought widely that the King had made a misalliance. This was relayed, foolishly, by Edward to his new bride, perhaps oblivious in those early days of her capabilities. A spiteful, vindictive Elizabeth had stolen the seal from her husband’s purse as he slept and had written to Tiptoft instructing him to get rid of Desmond. This begs the question of whether Tiptoft himself may have been unaware that the order did not emanate directly from the King. The rest is history and a dark and terrible day at Drogheda.

Moving forward some 16 years later in 1483 we have an extant letter from Richard to his councillor the Bishop of Annaghdown in which he instructs the said Bishop to go to Desmond’s son, James, and among other things to demonstrate (shewe) to him that the person responsible for the murder of his father was the same person responsible for the murder of George Duke of Clarence (1). As Annette Carson and Ashdown-Hill point out, this is a ‘ highly significant analogy‘ because, in 1483, Mancini had written that contemporary opinion was that the person responsible for Clarence’s death was no other than Elizabeth Wydville. Mancini pointed out that Elizabeth, no doubt having discovered that her marriage to Edward was a bigamous one – he already having a wife – namely Eleanor Butler nee Talbot, at the time of his ‘marriage’ to her, had

‘concluded that her offspring by the king would never come to the throne, unless Clarence was removed and this she easily persuaded the king’ (1).

It is highly likely that Clarence, who perhaps was of a hotheaded nature, had also become aware that Edward and Elizabeth’s marriage was null and void having been informed of this fact by Bishop Stillington. Stillington was imprisoned and Clarence met the same fate as Desmond – an execution regularly described by historians, of all views as a judicial murder.

George Duke of Clarence from the Rous Roll. George was only 28 years old when he was executed in what has been described by some historians as a ‘judicial murder’

George Duke of Clarence from the Rous Roll. George was only 28 years old when he was executed in what has been described by some historians as a ‘judicial murder’

It should also be remembered that shortly before his arrest Clarence had been widowed. Clarence had insisted that his wife, Isobel Neville, had been murdered – poisoned he said. One of the acts he was accused of at his trial was of trying to remove his small son, Edward, out of England and to safety abroad. He obviously genuinely believed that Isobel had indeed been murdered, why else attempt to get his son out of harms way? This story has been told in many places including Ashdown-Hill’s books, The Third Plantagenet as well as his bio of Elizabeth, Elizabeth Widville Lady Grey. If Isobel was indeed murdered, the truth has been lost with time, it can safely be said that Clarence was a victim to Elizabeth’s malice although of course Edward has to take equal blame for that. Hicks, and Thomas Penn, are among the historians who have described Clarences’ execution as ‘judicial murder’. Hicks in his bio on George, states that the trial held before a Parliament heavily packed out with Wydeville supporters was fixed. George stood not a chance and was led back to the Tower to await his fate. He did not have to wait too long. Penn writes ‘His brothers life in his hands, Edward pondered the enormity of his next, irrevocable command. A week or so later, with Parliament still in session, Speaker Allington and a group of MPs walked over to the House of Lords and, with, all decorum, requested that they ask the king to get on with it‘. Insisting that the king order his own brother’s liquidation was hardly something that Allington would have done on his own initiative. The source of the nudge could be guessed at (2). As Penn points out Speaker Allington’s ‘effusions about Queen Elizabeth and the little Prince of Wales were a matter of parliamentary record; the queen had awarded him handsomely appointing him one of the prince’s chancellors and chancellor of the boy’s administration’. Thus George Duke of Clarence was toast and it appears the second victim to the malignity of the Wydeville queen. Later it was written by Virgil that Edward bitterly regretted his brother’s ‘murder’ for thus it is described by Penn – and would often whinge when asked for a favour by someone that no-one had requested a reprieve for George (not even the brothers’ mother??? Really Edward!).

Elizabeth Wydville, The Luton Guildbook. Cicely Neville, her mother in law is depicted behind her. Cicely’s feelings on one of her son’s bringing about the death of another son are unrecorded.

Another damning point against Elizabeth is that Richard III in the communication mentioned above, granted permission to James, Desmond’s son, to ‘pursue by means of law those whom he held responsible for his father’s death’. Both Edward and Tiptoft were dead at this time but Elizabeth was still alive and demoted from Queen to a commoner. As it transpired James did not pursue the matter at that time and a year later it was all too late – Richard was dead and Elizabeth having been reinstated as Queen Dowager was the new king’s mother-in-law. Further evidence regarding Elizabeth’s guilt came to light 60 years later in the 16th century in the form of a memorandum addressed by James 13th Earl of Desmond, Desmond’s grandson, to the privy council. In an attempt to get property that had been removed from one of his ancestors returned to him James referred to the great privilege that was awarded to his earlier Desmond relatives, that of not having to appear before Anglo Irish authorities that had been granted by Edward IV because ‘the 7th Earl of Desmond had been executed because of the spite and envy of Elizabeth Wydeville”. This memorandum also contained the earliest written account of the conversation between Edward IV and Desmond regarding Elizabeth’s suitablity as a royal consort, the repeating of which to Elizabeth had resulted in Desmond’s murder.

It’s now not looking good for Elizabeth at this stage. There are other names, other deaths, that begin now to look rather suspicious. After all if Elizabeth could be involved with two deaths could there have been more?

The next deaths that need consideration are those of Eleanor Butler and her brother in law, the Mowbray Duke of Norfolk. According to Ashdown-Hill, who has researched Eleanor in depth, her death occurred while her family and protectors, particularly her sister Elizabeth Duchess of Norfolk, with whom she appears to have been close, were out of the country attending the marriage celebrations of Margaret of York to Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy. This marriage had been ‘pushed forward’ by Elizabeth Wydeville (3). Of course her death may have been the result of natural causes although it’s not hard to imagine Edward and Elizabeth breathing massive sighs of relief. However karma is a bitch, as they say, and the spectre of Eleanor would later arise with tragic results and the complete fall of the House of York.

Whether Eleanor died of unnatural causes of course can now never be ascertained. However Ashdown-Hill has compared her death to that of Isobel Neville (4). Certainly it was unexpected and must have caused shock and grief to her sister on her arrival back in England – presumably the Duchess may not have left England and her sister if she had been seriously ill and close to death. In actual fact Eleanor died on the 30th June 1468 while Elizabeth Talbot only begun her trip back to England from Flanders on the 13th July. Coupled with this, two of the Norfolk household were executed around this time through treasonous activity but nevertheless this must have caused disconcertment and fear to the Duke and Duchess following on so soon from Eleanor’s death. Very sadly, the Duke himself was to die suddenly and totally unexpectedly. The now Dowager Duchess of Norfolk, bereft of her husband and sister, found herself forced to agree to the marriage of her very young daughter, the immensely rich heiress, Anne Mowbray, to Elizabeth Wydeville’s youngest son, Richard of Shrewsbury. This was much to her detriment being forced to accept a diminished dower in order to supplement the revenue of her young son in law. She thereafter lived out her days in a ‘great’ house in the precincts of the Abbey of the Minoresses of St Clare without Aldgate, poorer but surrounded by loyal and loving friends most of whom had also suffered at the hands of Edward IV and the Wydevilles (5).

In summary, I’m confident that Elizabeth was deeply implicated in the executions of Desmond, an entirely innocent man, and Clarence whom she feared because he knew or suspected the truth of her bigamous marriage. Could there have been others? The hapless Eleanor Talbot perhaps? Of course she was not a murderess in the sense that she actually and physically killed anyone but she did indeed ‘load the guns and let others fire the bullets’ as they say. There is little doubt that Richard Duke of Gloucester came close to being assassinated on his journey to London and close to the stronghold of the Wydevilles at Grafton Regis, in 1483. This was down to the machinations of the Wydevilles including of course the fragrant Elizabeth who by the time he arrived in London had scarpered across the road from Westminster Palace, loaded down with royal treasure, and taken sanctuary in Westminster Abbey , a sure indication of her guilt in that plot. Richard, in his well known letter, had to send to York for reinforcements:

“we heartily pray you to come to us in London in all the diligence you possibly can, with as many as you can make defensibly arrayed, there to aid and assist us against the queen, her bloody adherents and affinity, who have intended and do daily intend, to murder and utterly destroy usand our cousin the Duke of Buckingham, and the old blood royal of this realm” (6).

After that dreadful day at Bosworth in August 1485, and a bit of a tedious wait, Elizabeth now found herself exulted once again being mother to the new Queen. She would, one have thought, reached the stage where she could at last rest on her now rather blood soaked laurels. Wrong! She was soon found to be involved in the Lambert Simnel plot, which no doubt if successful would have resulted in the death of her daughter’s husband, Henry Tudor. Whether her daughter, Elizabeth of York, would have approved of this is a moot point and something we shall never know although surely she would hardly have welcomed being turfed off the throne and her children disinherited and my guess is that relationship between Elizabeth Snr and Jnr became rather frosty after that. Henry Tudor, who was many things but not a fool, took the sensible decision to have his mother in law ‘retired’ to Bermondsey Abbey, no doubt to protect her from herself but more importantly to protect himself from Elizabeth and her penchant for plots that mostly ended up with someone dead. And there at Bermondsey, a place known for disgraced queens to be sent to languish and die, she lived out her days no doubt closely watched, Karma having finally caught up with her.

Terracotta bust of Henry VII. Elizabeth’s son-in-law. Henry prudently had Elizabeth ‘retired’ to Bermondsey Abbey.

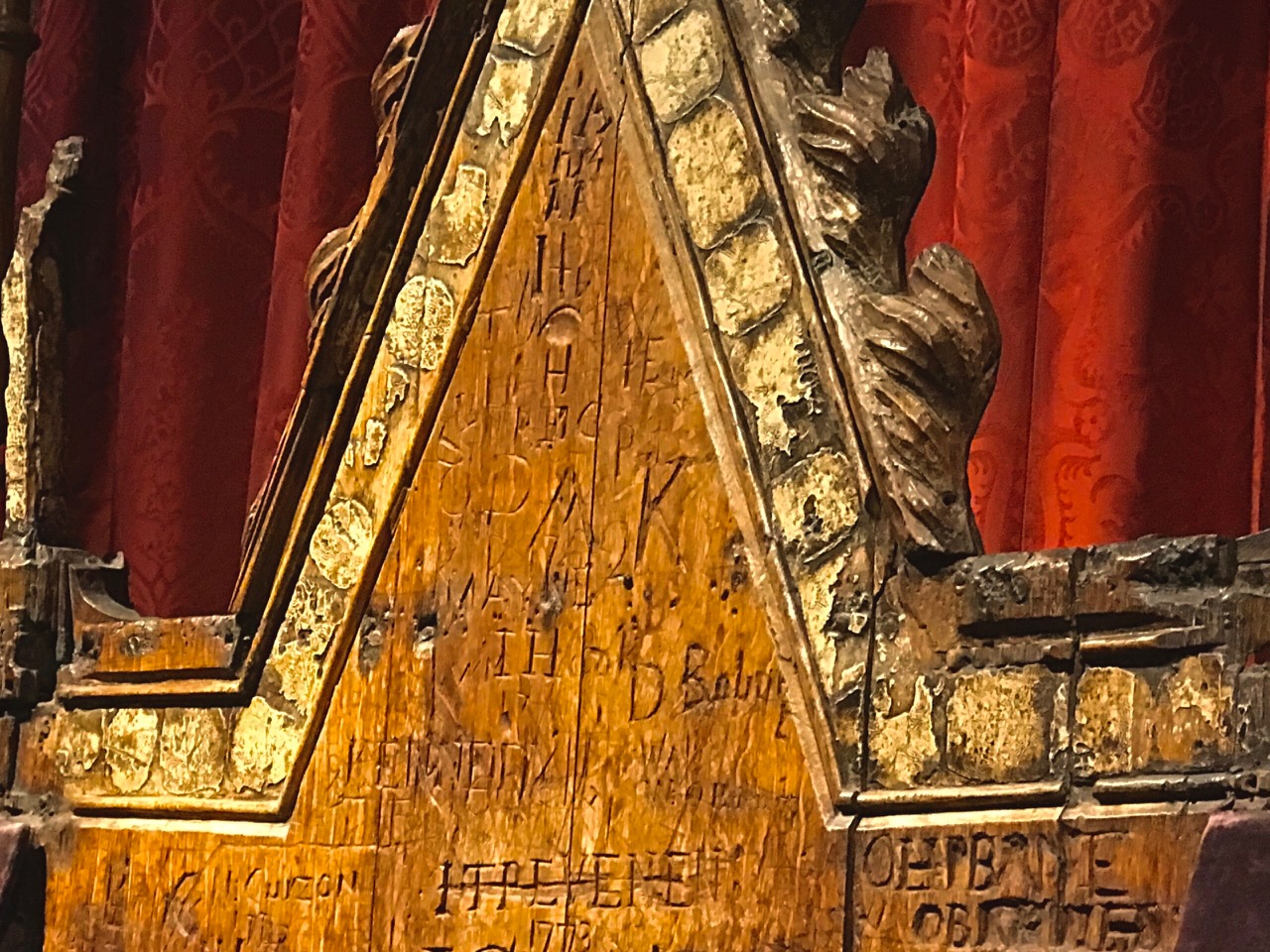

John Tiptoft Earl of Worcester. Effigy on his tomb. Tiptoft’s propensity for cruelty did not deter Edward from appointing him Lord Deputy of Ireland in 1467 nor did it dissuade Elizabeth to involve him in her plotting to bring about the death of Desmond.

If you enjoyed this post you might like:

The Abbey of the Minoresses of St Clare without Aldgate and the Ladies of the Minories

ELIZABETH TALBOT, VISCOUNTESS LISLE, LADY ELEANOR BUTLER’S NIECE

GEORGE DUKE OF CLARENCE, ISOBEL NEVILLE AND THE CLARENCE VAULT

Cheyneygates, Westminster Abbey, Elizabeth Woodville’s Pied-à-terre

THE MYSTERIOUS AFFAIR AT STONY STRATFORD by ANNETTE CARSON

ELIZABETH WYDEVILLE, JOHN TIPTOFT AND THE EARL OF DESMOND

(1) Harleian Manuscript 433 Vol 2 pp108.9

(2) The Usurpation of Richard III Dominic Mancini. Ed. C A J Armstrong.

(3 ) The Brothers York Thomas Penn p405

(4) Elizabeth Widville Lady Grey p87 John Ashdown Hill

(5) Ibid p124 John Ashdown Hill.

(6) The Ladies of the Minories W E Hampton. Article in The Ricardian 1978

(7) York Civic Records Vol.1.pp 73-4. Richard of Gloucester letter to the city of York 10 June 1483.

Here is

Here is

Arms of Queen Anne Neville @ British Library

Arms of Queen Anne Neville @ British Library