The Privy Purse Expenses of Elizabeth of York and The Wardrobe Accounts of Edward the Fourth Edited by Nicolas Harris Nicolas Esq

The Privy Purse Expenses of Elizabeth of York and The Wardrobe Accounts of Edward the Fourth Edited by Nicolas Harris Nicolas Esq

As demonstrated by my earlier posts on the subject I enjoy nothing more than a delve around privy purse/wardrobe expenses. This may be partly due to my naturally nosy nature but also because of how much they can tell you about that specific person. Take for example Elizabeth of York’s cheap lanten shoe buckles or her generosity to any person who rocked up who had been in the service or provided help for any of her relatives. Not to mention Henry VII’s penchant for dancing maidens – now theres a surprise! Here today are some of Edward IVs Wardobe Expenses. Good grief did that man love bling bling – the wonderful fabrics he wore, the jewels – how he must have shone and shimmered in the candlelight..

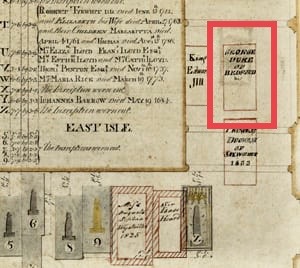

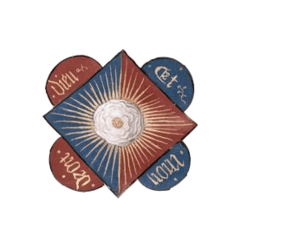

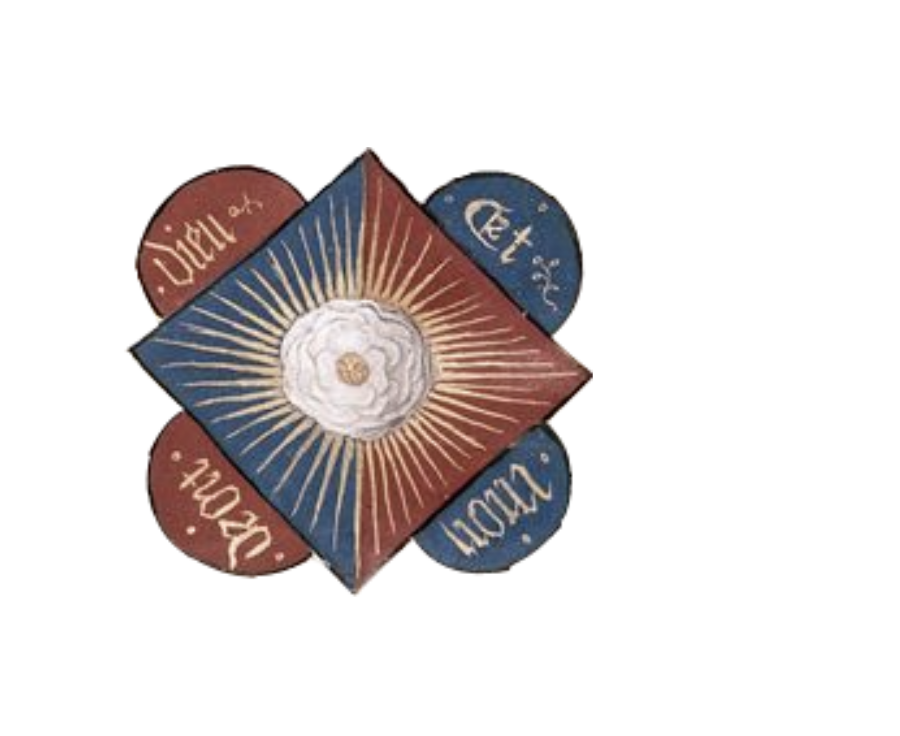

Edward IV motto, ‘confort et lyesse’,

However before I go further I should say I’m being unfair to call Edward King of Bling – all medieval monarchs knew the importance of dressing sumptuously, even Henry Tudor, who known for his meanness, except where it came to his funeral, had his helmets encrusted with jewels – yes he did! –

27th May 1492 ‘many precyous stones and riche perlis bought of Lambardes for the ‘garnyshing of salads, shapnes and helemytes’

June 30th 1497 £10 was paid to the Queen to cover her costs of ‘garnyshing of a salet’.

August 9th John Vandelft, a jeweller was paid £38.1s.4d for the ‘garnyshing of a salett‘ – Now thats what you call ostentatious!

A Helmet or Salet decorated. This is not Henry’s salet because his would have been more jewel encrusted and pretentious.

It was actually written by an ‘historian’ that, Richard III who was just being a medieval king, was a fop! (1). We have Sharon Turner (1768-1847) to thank for this gross misinterpretation of facts. Turner did not stop there and went on to also absurdly describe Richard as a ‘vain coxscomb‘ and we have the editor of The Wardrobe Accounts of Edward IV, Sir Nicolas Harris Nicolas, writing in 1830 to thank for righting this silliness. Sir Nicholas wrote that the

‘love of splendid clothes and taste for pomp belonged to the age and not to the individual‘ (2).

So we can clearly see all medieval kings were all naturally very blingy. However fortunately, or unfortunately, depending how Edward would have viewed people gawping over his expenditure, his wardrobe accounts are readily available for us to peruse. Mind you I do not think Edward himself would have cared a flying fig. Indeed he liked nothing better than to show off as Mancini has mentioned –

‘He was wont to show himself to those who wished to watch him and he seized any opportunity that the occasion offered of revealing his fine stature more protractedly and more evidently to onlookers’ (3).

So I feel he would just smile and roar ‘Yea I was magnificent!’ and indeed Edward you were, you were!

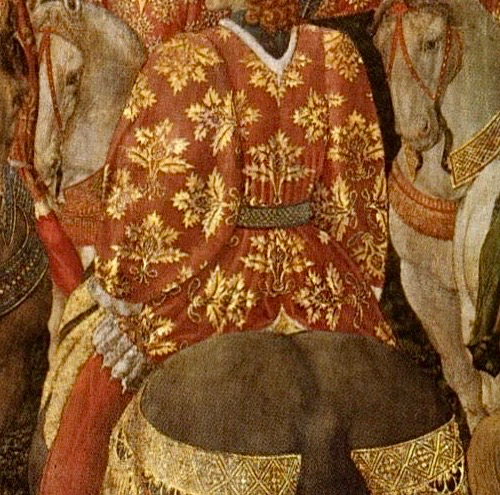

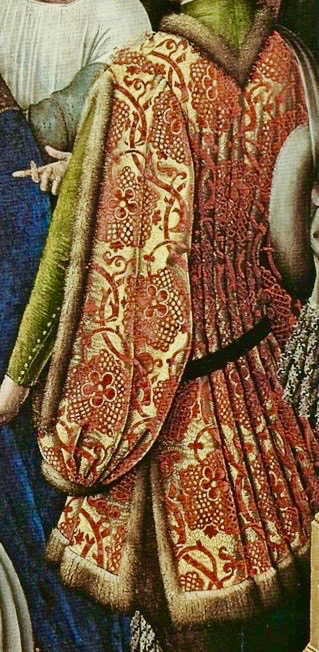

So herewith are a very small sample of the wonderous items in Edward’s Wardrobe Accounts that stand out for me, particularly the fabrics of which we can only imagine the sumptuousness, although scroll down for some details of fabrics from paintings from that era

Items of clothing included :

A longe gowne made of blue clothe of gold uppon Satyn ground emaylled and lyned with green satin

A longe gowne of grene velvet upon velvet tisshue of gold and a long gowne of white velvet upon velvet tissue of gold; both gownes lined with blac satyn

A demy gown of grene velvet and a gowne of grene damask both lyned with blac satyn

A doublet of purpulle satyn and a doublet of crymysyn velvet lined with Holand clothe interlined with busk

A loose gowne of velvet upon velvet blac clothe of gold furrid with ermyns

A demy gowne made of tawny velvett lyned with blac damask;

A demy gowne made of blac velvet lyned with purpulle satyn ;

A demy gowne made of grene velvet lyned with blac damask;

A demy gowne of purpulle velvet double lyned with green sarsinette;

A jaket of blue clothe of gold emayled not lined

A longe gowne of white damask furrid with fyne sables

To make further items of clothing fabrics were purchased including .

For crimson velvet of Montpilier in Gascony at xiiij s the yard ; Black cloth of gold at xl s.the yard ; velvet upon velvet white tysshue cloth of golde ; velvet uppon velvet grene tisshue cloth of golde at xl s. the yarde ; cloth of gold broched upon satyn grounde at xxiij s. the yard ; blue clothe of silver broched uppon satyn ground at xxiiij s. the yard

For white damask with floures of diverse colours at viij s. the yard ; damask cremysyn and blue with floures at vj s. the yard ; Black Velvet speckled with white ; Blue velvet figured with tawney iiij s. the yard

For white velvet with black spots ; Chekkered velvet ; Grene chaungeable velvet ; velvet purpull ray and white ; velvet russet figury ; velvet cremysyn figured with white at viij s.the yard

Cremysyn clothe of golde the grounde satyn viiij s. the yard

To the famous Alice Claver ‘sylkwoman’ ;

For brode ryban of blak silk for girdelles at xv d. the ounce ; ryban of silk for poynts laces and girdles xiv d. the ounce ; a mantell lace of blue silk with botons of the same xvij s. ; frenge of gold of Venys at vj s. the ounce ; a garter of rudde richeley wrought with silke and golde xvij s. …..

To complete his ensemble Edward would have required shoes, boots and slippers and lots of them

A Peter Herten, cordswainer , supplied some of these –

A pair of Bootes of blac leder above the kne price vj s. ; ij paires of Bootes oon of rede Spaynyssh leder and the other tawny Spaynyssh leder viij s. ; a pair of shoon double soled of blac ledre doulble soled and not lyned price v d. ; viij paire of sloppes (A type of shoe) lyned with blac velvet vij d. the pair ..

and of course socks were needed – Sokkes of fustian iiij pair…

Of course no outfit is complete without a hat…

For iiij hattes of wolle the pece xij d. ; for bonetts ij s. every pece – clearly Edward got through a lot of hats!

For the xj ostrich feders to adorn the hats ; x s.every pece.

Hose was required – obvously: To a Richard Andrew, citezen and hosier of London, for making and lyning of vj pair of hosen of puke (nowadays known as puce..thank goodness!) lyned, every pair iij s. iiijd.

A nice pair of spurs was needed : For a paire of blac spurs parcell gilt v s. ; spurres longe, a pair, shorte, a pair…

Obviously someone had to be paid to make the fabrics into magnificent clothes – step forward George Lufkyn and take a bow. Mr Lufkyn, taylor, was paid for the making of :

doublettes of purpull velvet, for every doublet making with the inner stuff unto the same vj s. ; for the making of iij long gownes of cloth of gold, iij long gownes of velvet; vj demy gownes and a shorte loose gowne of velvet and damask, for every gown making iij s. iiij d.; for making of a jacket of cloth of gold ij s.and for the making of a mantel of blue velvet vij s.

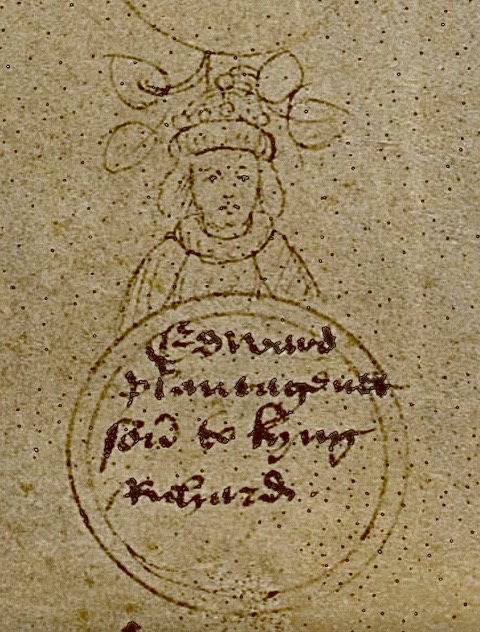

Edward’s sons did not miss out –

To Prince Edward : white cloth of gold tisshue for a gowne, v yerdes…

To the righy highe and myghty Prince Richard Duke of York : A mantelle of blue velvet lined with white damask garnissht with a garter of ruddeur and a lase of blue silk with botons of golde ; v yerdes of purpulle velvet and v yerdes of green velvet ; white cloth of gold for a gown, tissue cloth of golde; v yerdes of blac satyn and v yerdes of purulle velvet for lynyng of the same gown…

Even the young Earle of Warwick was generously catered for : A peire of shoon of blue leder; a peire of shoon of Spanynyssh leder; a peire of botews of tawny Spanynyssh leder

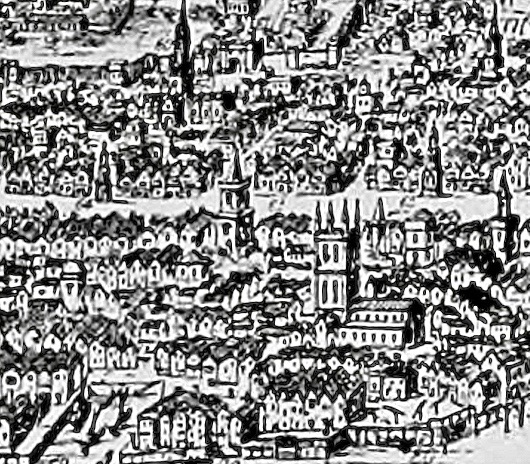

The majority of these examples are taken from the wonderful paintings of Jan Van Eyck a Flemish painter

It nice to know that besides the people these glorious fabrics etc., were purchased and made into sublime clothing for, the names of the people that supplied and toiled away at making the garments, shoes, boots, hosery, laces, ribbons and hats have come down to us. So remembering those industrious citizens, artisans and merchants including Piers Courteys/Curteys, Keeper of the Kings Great Wardrobe, Alice Claver, lace maker, Richard Rawson, Piers Draper, John Poyntmaker (this gentleman’s name is self explatory) John Caster, skynner, Petir Herton, cordewaner, William Dunkam and William Halle taillours and Robert Boylet (surely an appropriate name) for washing the sheets.

I hope dear reader you have enjoyed this short meander through Edward IV’s Wardrobe Accounts. If you have you may like to take a look at my posts concerning Privy Purse expenses – just click on the links..

The Privy Purse Expenses of Henry VII

Elizabeth of York – Her Privy Purse Expenses

I have of course drawn heavily from The Privy Purse Expenses of Elizabeth of York : Wardrobe Accounts of Edward the Fourth. Editor Nicholas Harris Nicolas

(1) Richard III as a Fop: A Foolish Myth Anne F Sutton. Ricardian 2008 Vol 18

(2) Wardrobe Accounts of Edward the Fourth Editor Nicolas Harris Nicolas. Introductory remarks p.iv

(3) The Usurpation of Richard III Dominic Mancini. Translated by C A J Armstrong p65