‘I came in my might like a sun in splendour, Soon suddenly bathed in my own blood’

George duke of Clarence’s epitaph – Tewkesbury Abbey.

This is thought to be a portrait of Isobel from the Luton Guild Book. See The Dragonhound’s interesting post here

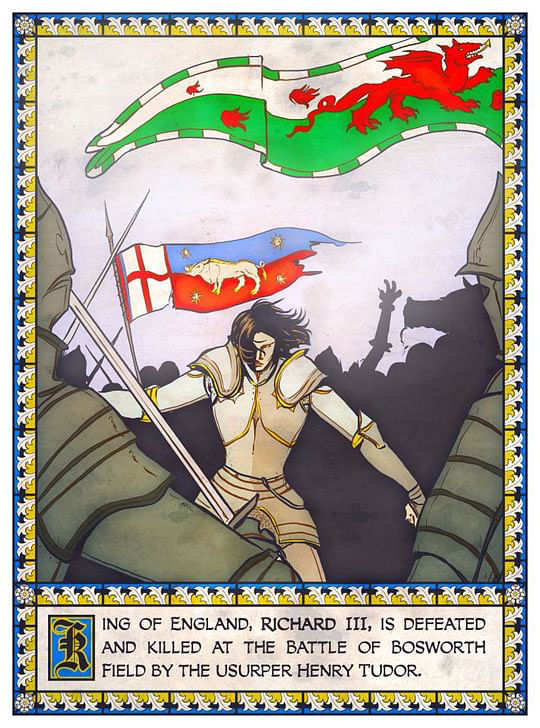

After the death of Isobel Duchess of Clarence on the 22 December 1476 aged 25, her coffin lay in repose on a hearse for thirty-five days in the midst of the choir of Tewkesbury Abbey while a vault was constructed, ‘artificialiter’, behind the high altar facing the entrance to the eastern Lady Chapel (1). Hicks, George’s biographer wrote how the widower ‘… took great pains over her exequies’ and Isobel was finally laid to rest on the 8 February 1477. Just over a year later following his execution on the 18 February 1478, her husband, aged 28, was to join her in their tomb.

On the 20 February Dr Thomas Langton, a royal councillor wrote in a letter ‘Ther be assigned certen Lords to go with the body of the Dukys of Clarence to Teuxbury, where he shall be beryid; the Kyng intends to do right worshipfully for his sowle’.

George Duke Clarence. Rous Roll. Motto ex Honore de Clare.

Could this be a portrait of George, in blue, and Richard the figure in green? Luton Guild Book. See here for the Dragonhounds interesting theory.

Could this be a portrait of George, in blue, and Richard the figure in green? Luton Guild Book. See here for the Dragonhounds interesting theory.

Much has been written on George and his life and death, not quite so much about Isobel. Isobel, daughter of Richard Neville, the Earl of Warwick, who became known as the Kingmaker and Anne Beauchamp and thus sister to Anne, then Duchess of Gloucester, later Queen to Richard III, never recovered after giving birth to a son at the infirmary of Tewkesbury Abbey on the 5 October 1476. It’s not known why Isobel would have given birth in the Abbey infirmary and not in the comfort of her home, Warwick Castle. Could this indicate that she was ill prior to going into labour? The next day the baby, a boy named Richard, was baptised in the nave of the Abbey. Whether or not Isobel was ill prior to giving birth, she never recovered fully afterwards and was taken home to Warwick Castle on November 12th where she died on the 22nd December, her baby son dying around the same time. It has been presumed that her death was brought about by childbirth and/or consumption. There are indications that George loved and mourned Isobel and Hicks suggests it may be taken as a ‘sign of his continuing sense of loss’ that six months later Isobel was enrolled posthumously when George and their two surviving children were admitted to the Guild of the Holy Cross at Stratford-upon-Avon (2 ). Unusually for the times there is no evidence he was ever unfaithful to Isobel with no known mistresses or illegitimate children. This was rare for a man of the nobility in the 15th century. George was adamant that she and their son had both died of poisoning. So convinced was George that he attempted to send his surviving son, Edward, out of the country to somewhere he would be safe. Whether he was successful or not is a moot point. Some theorise he succeeded in this venture but it is generally accepted that it was his son who was placed in the Tower of London after Bosworth where he remained until his execution on the 28 November 1499. George was judicially murdered in what has been described as the ‘first act of self-immolation of the Yorkist monarchy by Edward IV’ which ‘reverberated throughout the nobility with tragic consequences in 1483‘ (3). George was laid to rest beside Isobel and his now parentless children left to their fates.

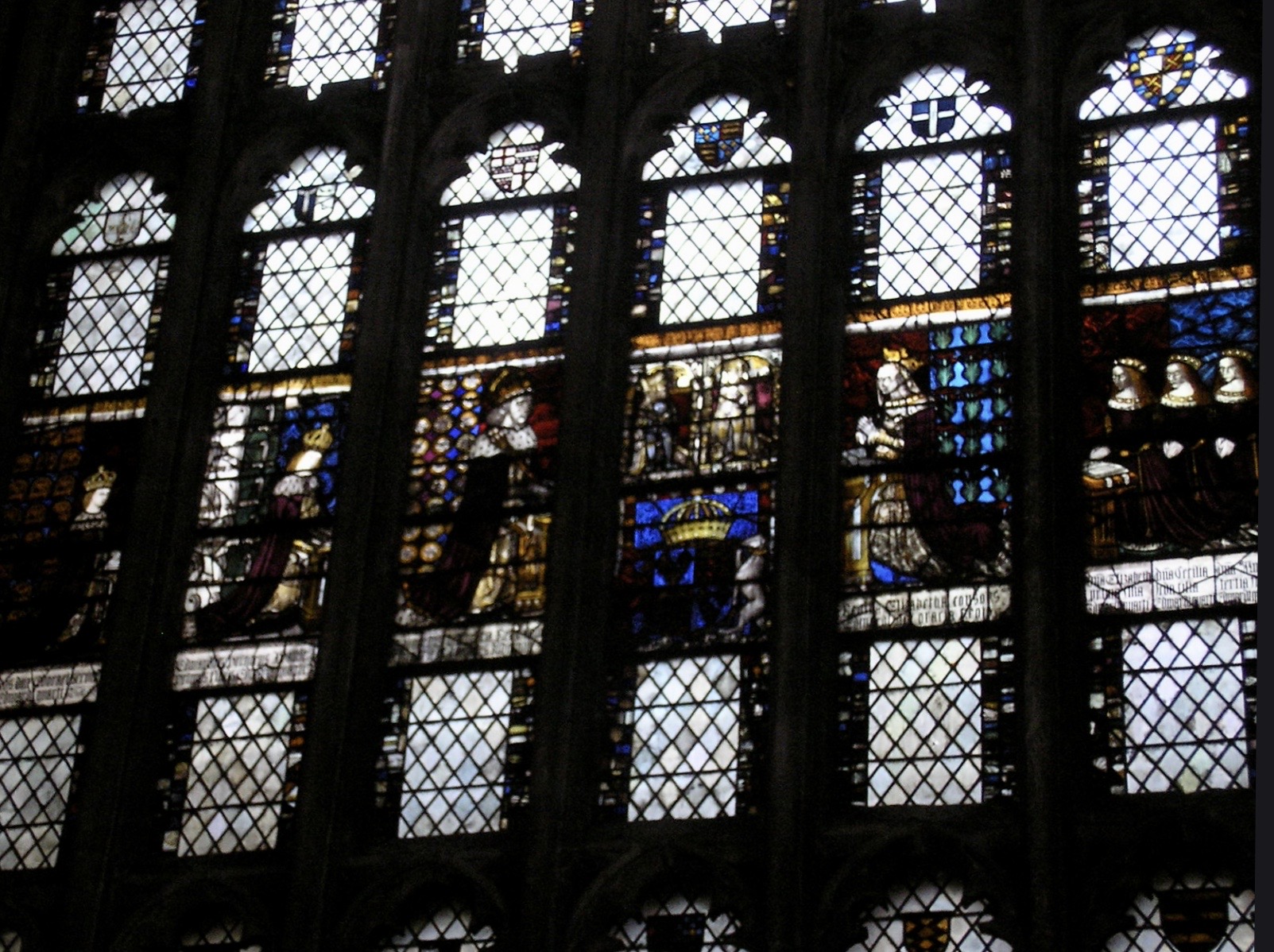

Isobel and George Duke and Duchess of Clarence. The Rous Roll. British Library.

Isobel Neville, Duchess of Clarence. Rous Roll. The British Library.

I will not go into the rows, accusations, counter accusations and shenanigans that had led to the great falling out between the royal brothers. It’s documented elsewhere and I would recommend Hicks’ False, Fleeting, Perjur’d Clarence 1449-78 for anyone who would like to delve deeper into George’s story. The end came when George bravely but rashly had Thomas Burdett’s declaration of innocence, which had been made on the scaffold before his execution, read out to the royal council. John Stacey, Burdett’s co-defendant also proclaimed his innocence on the scaffold, his voice weaker, probably because of the torture that he had endured. Is it likely that a medieval man in those pious times would have been prepared to go to meet his Maker with a lie upon his lips? I think not. Thomas Penn in his book The Brothers York notes a similar case in 1441 when two astrologers, Bolingbroke and Southwell had been arrested on much the same charges, that time predicting Henry VI’s death. Pen suggests this case could have been the blue print for the Burdett and Stacey case. George’s goose was well and truly cooked and an enraged King Edward summoned George and before a parliament ‘stage-managed‘ and thronged with sycophants and a trial ‘very carefully prepared apparently by the Wydevilles‘ with witnesses doubling as prosecutors, it was ensured George stood not a cat’s chance in Hell. His prediction that Edward ‘entended to consume hym in like wyse as a Candell consumeth in brennyng’ proved correct. The most reliable narrative, that of the Croyland Chronicler, who appears to have been an eyewitness at the trial and was clearly shocked, indicates that it was not ‘conducted in a manner conducive to justice’ and that George was offered inadequate opportunity for defence (4). Hick’s writes that the Act of Attainder ‘although long is insubstantial and imprecise and it is questionable whether many of the charges were treasonable, some were covered by earlier pardons, some seem improbable, none is substantiated and certainly no accomplishes were named or tried‘. The sentence was of course that of death and a vacillating Edward was finally pushed into proceeding with his brother’s execution. After the deed was accomplished Edward ‘provided for an expensive funeral, monument, and Chantry foundation at Tewkesbury Abbey’ which, frankly, was the very least he could do under the circumstances. There are indications Edward regretted his brother’s execution and that ‘he bewailed his brother’s death’. As well as Sir Thomas More and Holinshed’s Chronicle remarking on it Virgil also wrote ‘yt ys very lykly that king Edward right soone repentyd that dede; for, as men say, whan so ever any sewyd for saving a mans lyfe, he was woont to cry owt in a rage ‘O infortunate broother, for whose lyfe no man in this world wold once make request’ (5). Edward, presumably filled with guilt, floundered around, blaming everyone else for what was the judicial murder of his brother except those truly responsible, himself and his Wydeville wife, One can only imagine the pain of their mother, Cicely Neville. The third brother, Richard Duke of Gloucester, later King Richard III was said by Mancini to be so. ‘overcome with grief that he could not dissimulate so well, but that he was overheard to say that he would one day avenge his brother’s death’ (6).

After the burial of George, the vault was sealed and a large blue flat stone was laid over the entrance with an inlaid funerary brass which may have depicted George and Isobel. This blue stone was still in place in 1826 although the brass itself had long since disappeared. Besides the vault there was also once a magnificent monument incorporating their effigies which completed the ring of Despenser tombs around the abbey choir (7). Nothing remains of that monument today.

The entrance to the Clarence Vault, Tewkesbury Abbey. Photo with thanks to the Wars of the Roses Catalogue.

A glass box in the Tewkesbury Abbey was long thought to have contained the remaining bones of George and Isobel but does it? Confusingly the vault had been opened, desecrated and pillaged several times over the centuries perhaps at the Dissolution and in 1509 when the Lady Chapel was demolished but definitely three times in the 18th century when in 1709, in the most reprehensible outrage, the royal remains were displaced to make room for the coffin of a “periwig-pated alderman” by name of Samuel Hawling and later on, in 1729 and 1753, his wife and son who were also interred there (8). This situation was belatedly put right in 1829 when the Hawlings were in their turn ejected from the vault and rightfully so. On that occasion some bones unconnected to the Hawlings that remained in the vault were presumed to be those of the Clarences and placed in a small ancient stone coffin that had been discovered elsewhere in the Abbey.

The Glass Box containing the bones from the Clarence Vault. Photo The Wars of the Roses Catalogue

In 1876 the vault was opened again to enable the laying of a new pavement in the ambulatory. The stone coffin in which the bones that had been supposed to be those of the Clarences had been placed was found to be filled with water, Tewkesbury being prone to flooding. It seems the bones were cleaned and then placed in a glass box. It is unclear if this is the same box where they remain to this day. The opening to the vault was then fitted with iron gates, and in the pavement over the vault a brass inserted engraved with two suns in splendour, the badge of the House of York. with the inscription, composed by a Mr. J.T.D. Niblett:

Dominus Georgius Plantagenet dux Clarencius et Domina Isabelle Neville, uxor ejus qui obierunt haec 12 Decembris, A.D. 1476, ille 18 Feb., 1477.

Macte veni sicut sol in splendore, Mox subito mersus in cruore.

Which translates thus..

‘Lord George Plantagenet, Duke of Clarence, and Lady Isabelle Neville, his wife, who died, she on Dec. 12, 1476, he on Feb. 18, 1477.

I came in my might like a sun in splendour, Soon suddenly bathed in my own blood’

….. a fitting epitaph for a man I always think lived his life like a dazzling firework, zooming through the air before finally falling to the earth spent and dying. Virgil reported his ‘comeliness’ alarmed an angst ridden Elizabeth Wydeville who feared it made him appear worthy of the crown. Another reason George had to go! It’s both annoying and frustrating George is too often seen as a one dimensional character, almost bordering on a pantomime villain, accused of being a traitor, drunkard, turncoat etc., etc.,even a lunatic. In fiction he has regularly been depicted as a nasty piece of work and even in one very popular novel bashing his young sister-in-law Anne Neville and giving her a cut lip. Certainly the Ankarette Twynhoe affair is a blot on his copy book, a strange story lacking clarity and which so far has never been explained satisfactorily. No historian has ever come up with a plausible reason why George acted in the way he did preferring in the main to go down the well trodden route that he was a bad man and not wired up right. Give Me Strength! Could it be possible that Isobel and her baby were indeed poisoned which would explain something which otherwise makes little sense, is totally irrational plus making George’s rage understandable. If a link between Ankarette, the Twynhoes and Elizabeth Wydeville could be discovered the whole scenario would then fall nicely into place. It would also be an explanation as to why Isobel was in the Infirmary at Tewkesbury prior to going into labour when surely the most comfortable place for her to have given birth would have been at home at Warwick Castle? Clearly she was ailing from something but what? I think we should at the very least keep an open mind on what is a very puzzling episode rather than leaving it that George simply threw a wobbly, arrested an innocent, elderly lady and had her executed just to prove he could and to wind Edward up. Yeah right! as they say in South London.

Another thing I find baffling is the general perception held by many historians of George and Warwick’s rebellion particularly in Warwick’s case which paints them as traitors of the most execrable kind. Warwick was clearly provoked beyond endurance by the rise and rise of the grasping, popinjay Wydevilles, coupled with Edward’s cavalier attitude towards him. Indeed I cannot blame them for it and I think their actions to rid the world of these odious people should be praised not maligned. The Wydeville marriage was, after all, the rock that the House of York foundered upon. Regarding the drunkenness charge, the late historian John Ashdown Hill pointed out there is nothing in contemporary records that suggest George was a drunk and it’s merely a silly myth on the same lines as Richard III’s ‘hump’ and withered arm. Bravo John! Unfortunately the winner gets to write history.

But back to the vault. in 1982 the bones were give the first modern examination by Dr Michael Donmall. They consisted, it would seem, of parts of two skulls, an assortment of long bones, pelvic and shoulder fragments , parts of a spinal column and some foot bones. The age of the skull deemed to be that of a male was estimated to be in the range of 40-60 years and the female 50-70 years. Both individuals were described by Dr Donmall as showing age related arthritic changes. This would, alas, rule out they were the remains of George and Isobel.

In 2013 the bones were re-examined by Doctor Joyce Filyer who muddied the waters further by suggesting that the bones were those of more than two individuals. Doctor Filyer however agreed with the 1982 findings that the two individuals were too old to be the Clarences. However Dr John Ashdown Hill suggested that the damaged skull may not not have belonged to the male’s bones and it is just possible this may be what remains of George’s skull. John bases this on the fact that some years prior to death the individual had suffered a cut to the front of the skull which had healed. This would be consistent with the ‘report that George suffered an injury at the Battle of Barnet six years prior to his death’. However it should be remembered that the nature of George’s battle injury is unknown. Dr Ashdown-Hill goes on to mention that there are also some very fragmentary bones included which are the remains of a ‘very slender woman who appears to have died in her twenties and that these may comprise surviving fragments of the body of Isobel Neville, Duchess of Clarence‘. So does the glass box indeed hold at least some of the remains of the Clarences or is it just wishful thinking?

A further view of the Clarence Vault. Photo @ The Wars of the Roses catalogue.

Like his brother Richard, George has suffered from the brilliant pen of William Shakespeare, who described him as ‘False, Fleeting, Perjur’d‘. Shakespeare also lay the responsibility of George’s death at the door of his brother Richard, then Duke of Gloucester. Perhaps he had not read Mancini’s comments although it probably would not have made any difference. It should be remembered that George was a man of his times, who had flaws but his good points are regularly overlooked. As Hicks wrote the Croyland Chronicler paid tribute to his ability and dangerous popularity, ‘an idol of the multitude‘. The Salisbury Cathedral chapter act book observed ‘Thanks be to God who has given such a benevolent and devout prince into the tutelage of the church’. Lets leave the final word with John Rous who would have met him and described him thus..‘…a myghty prince, femly of perfon and ryght witty and wel visaged. a gret almys geuer and a grete bylder as showis at tutbure (Tutbury) warrewik (Warwick) and odre placis and there was he purposed to have doone many grete thinges as wallyng the town..and at Gypclyf (Guy’s Cliffe) to have performyd the wil and purpos of hys fadre in law (Richard Neville Earl of Warwick) and to have gete privilages to his burges of Warrewik but froward forteon maligned foor a geyn him and leyd al a parte’.

- The Abbey Church of Tewkesbury H J L J Massé

- False, Fleeting, Perjur’d Clarence M A Hicks

- Last Champion of York: Francis Lovell, Richard III’s Truest Friend p. 49. Stephen David.

- Ibid p141

- Virgil 168

- The Usurpation og Richard III p.63 Dominic Mancini

- The Third Plantagent John Ashdown-Hill

- The Abbey Church of Tewkesbury H J L J Massé

If you have enjoyed this post you might like

Elizabeth Wydeville, John Tiptoft and the Earl of Desmond