Minster Lovell at sunset. Photo with thanks to Colin Whitaker

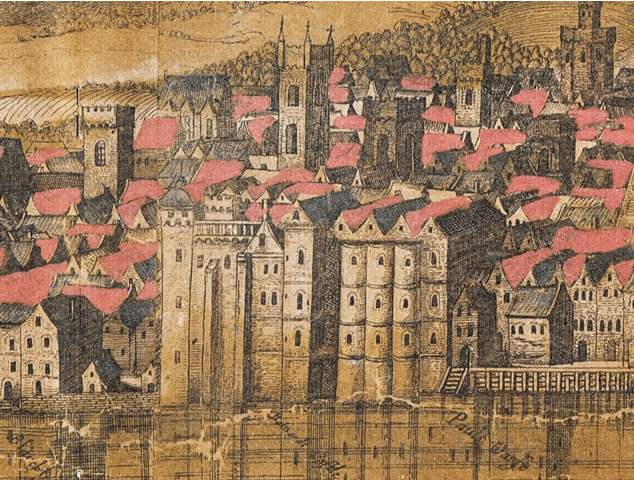

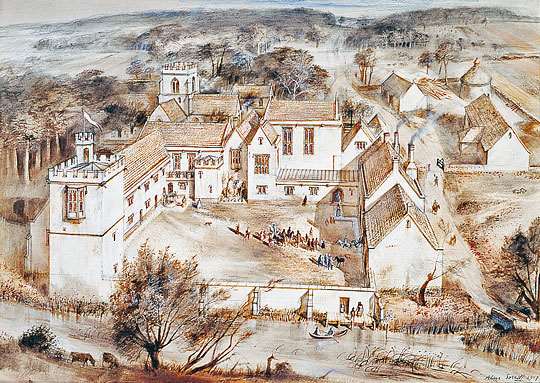

Minster Lovell Hall, Oxfordshire lies in beautiful, atmospheric ruins set amongst trees besides the River Windrush in the heart of the Cotswolds. Pevensey describes these ruins to be ‘still the most picturesque in the country’. It was at least the second manor house to be built by the Lovells on that site, the first having been built in the 12th century. William Lovell, Baron Lovell and Holand (d.13 June 1455) already rich and having increased his wealth by a very advantageous marriage, built the second Hall some time after his return from the wars in France in 1431(1). It’s unclear whether part of the earlier buildings were incorporated into the new one, as Pevensey suggests, or the old buildings were entirely demolished. But undoubtedly materials from the older buildings would have been recycled in the new build. The foundations of the earlier house were discovered beneath the east and west wings in the 1937/39. It remained home to the Lovells up until the Wars of the Roses.

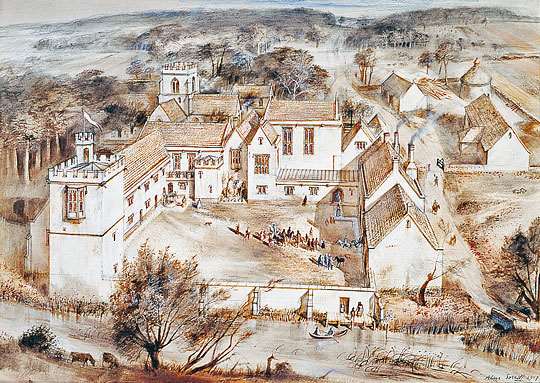

A drawing of the Hall as it may have appeared in the 15th c. Alan Sorrell

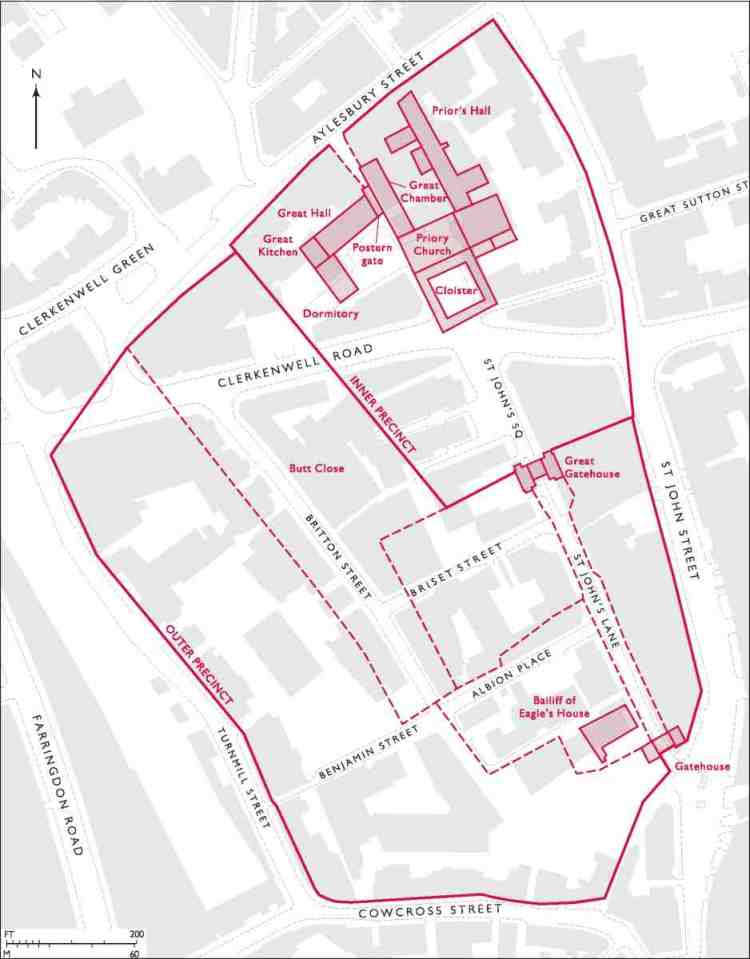

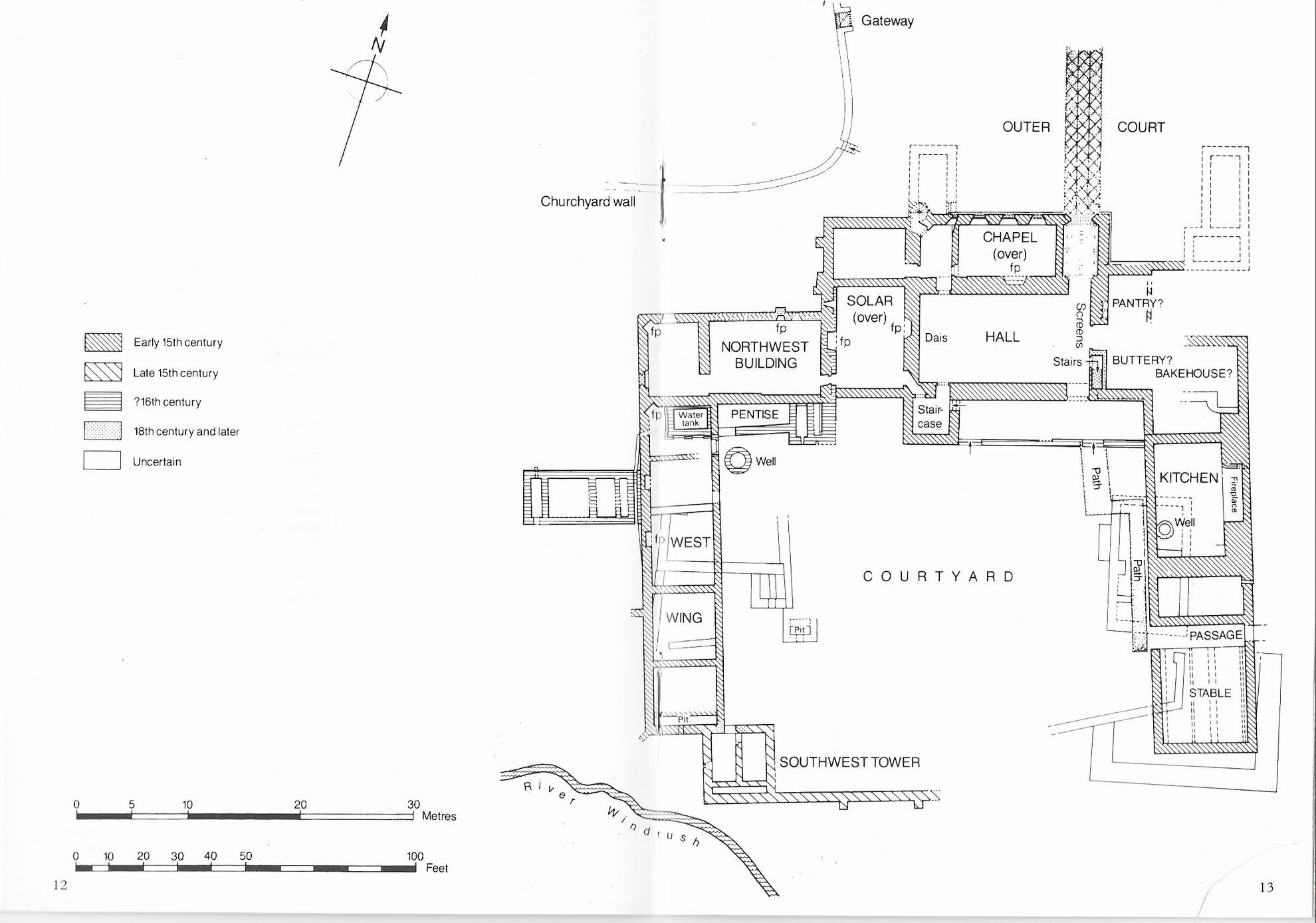

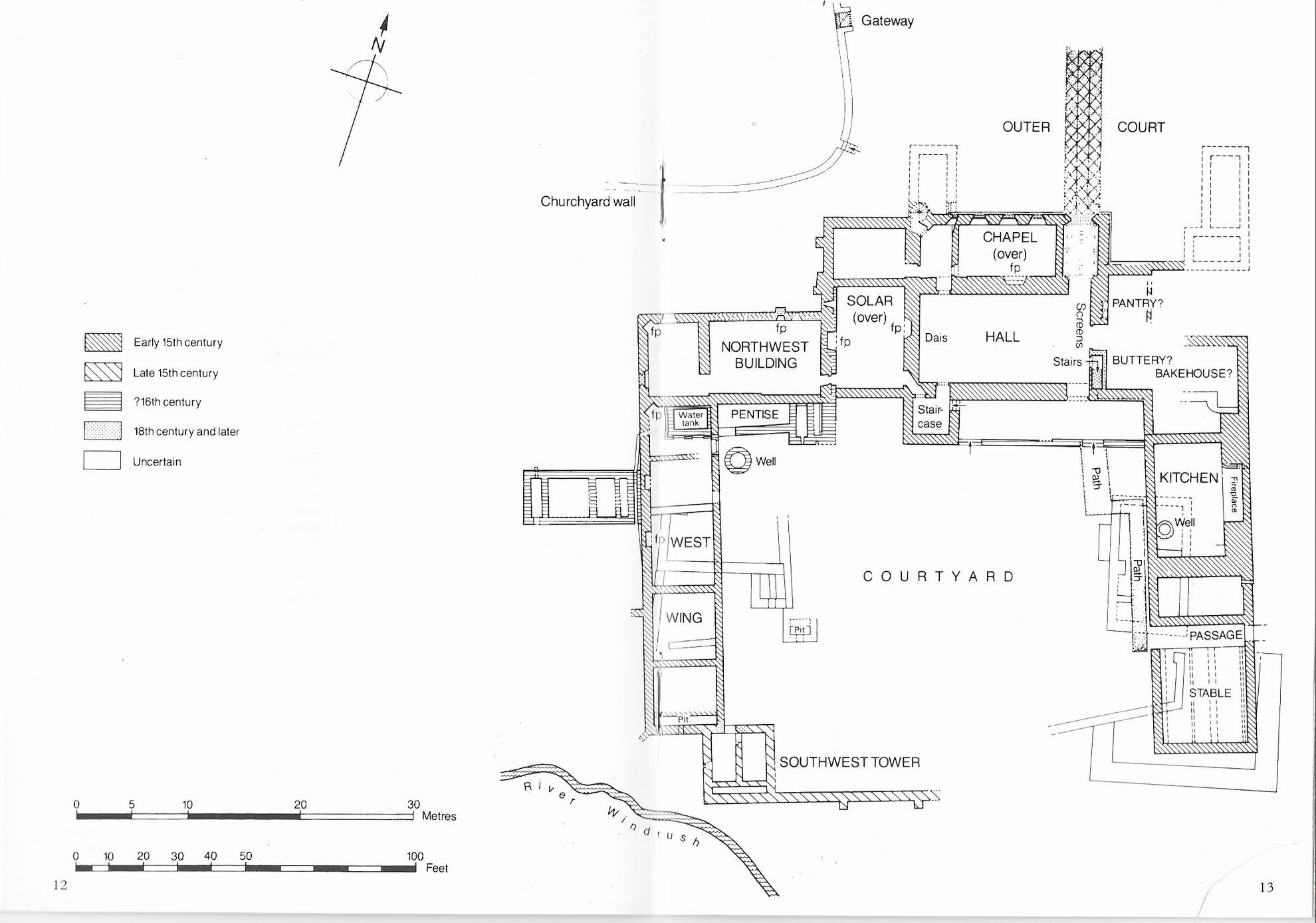

Site plan. Minster Lovell Hall English Heritage Guide Book. Photo A J Taylor.

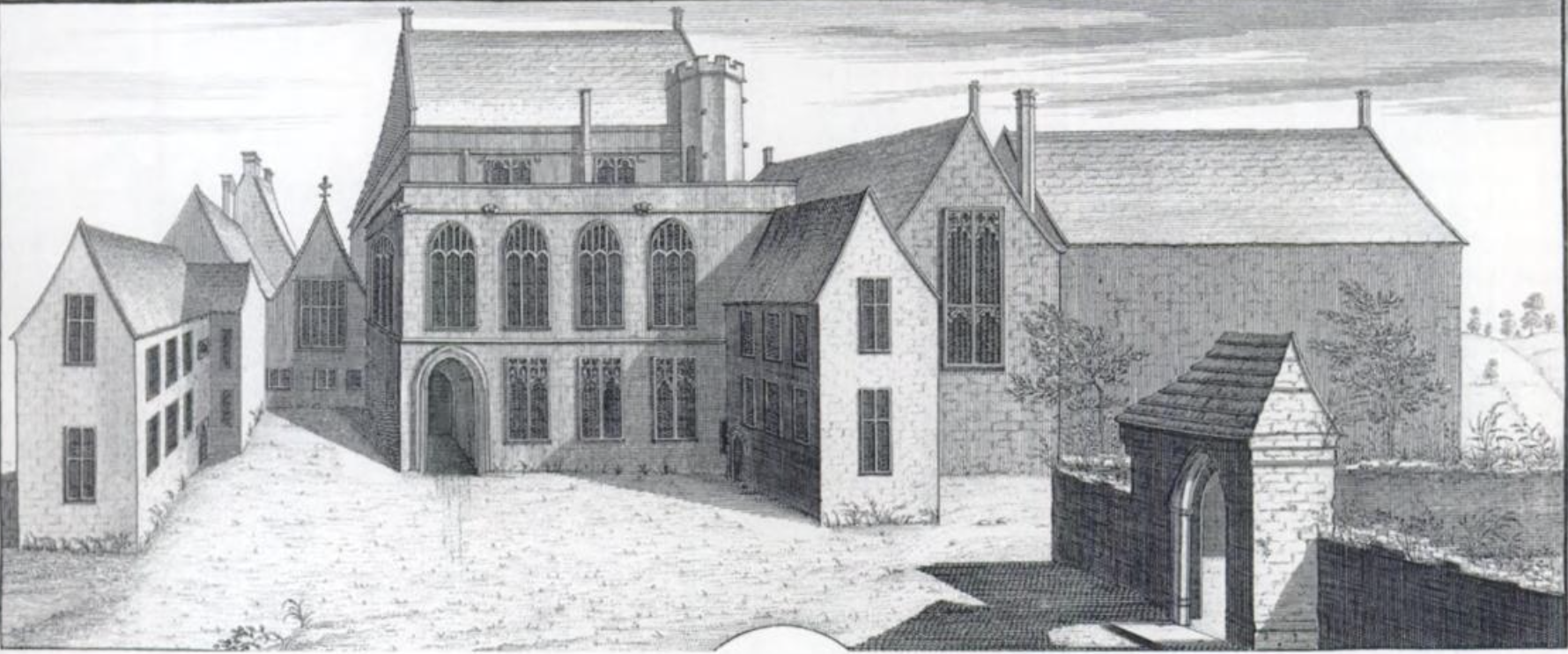

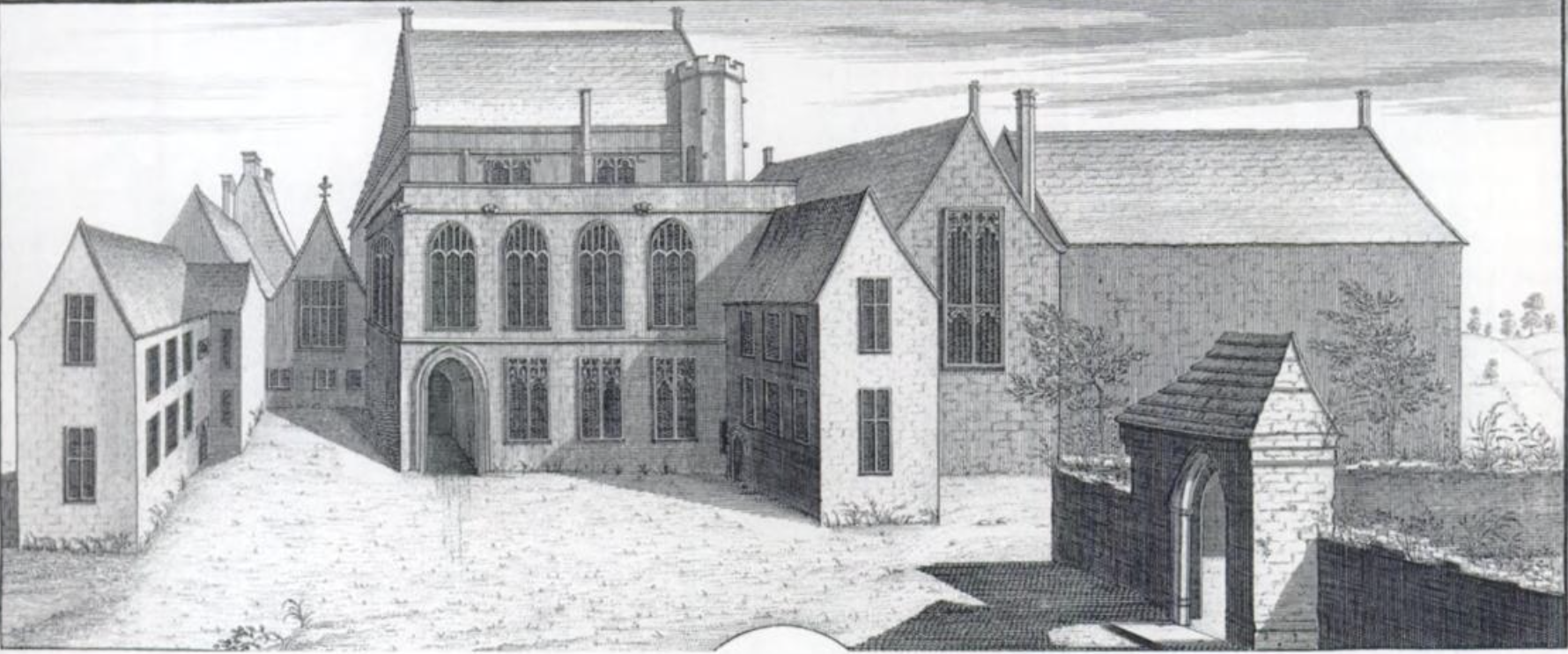

The porch and Hall from the north. Photo @ Guy Thornton

Same view of the porch and Hall from an engraving by Samuel and Nathaniel Buck 1729

Undoubtedly one of the best known of the Lovells – sometimes spelt Lovel – is Francis Lovell, Viscount Lovell b.1457. Francis was the son of John Lovell, Lord Lovell, who died in January 1464 and his mother was Joan Beaumont. By one of those strange quirks of fate, Joan, following the death of her husband in January 1464 had married none other than Sir William Stanley in 1465, dying in the following year. It would later transpire in 1485 at the Battle of Bosworth that Stanley would play a pivotal role in the defeat and death of Richard III to whom Francis was a close friend. But we skip too far here so back we go. Francis’ and Richard’s friendship dated back to their childhoods. Both had been wards of Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, known as the Kingmaker, with both spending part of their childhoods at Middleham Castle in Yorkshire although possibly not always at the same time. Francis’ life is well documented elsewhere and I don’t want to go into it too deeply here but suffice to say history has judged him rather kindly. He seldom fails to get a mention in any fictional work about Richard and as far as I can tell he generally comes over as a good egg. Of course there is the infamous rhyme that was pinned to the door of old St Paul’s : ‘The Cat, the Rat and Lovel our dogge, Rule all England under an Hog‘. The author of the rhyme, William Colyngbourne, was later to get the chop, or hung drawn and quartered to be precise, under a charge of treason for another matter, although I should imagine the rhyme was well and truely burnt into everyones memories present at the trial. Strangely enough Colyingbourne was once employed by Cicely Neville, Richard’s mother and its been suggested he may have copped the needle when Richard wrote to her on the 3 June 1484 requesting Colyngbourne’s position be transferred to someone of Richard’s choice – ‘my lord Chamberlaine..be your officer in Wiltshire in such as Colynborne had (2 ).

It was from Minster Lovell on Tuesday 29th July 1483 very soon after his coronation and while on royal progress that Richard III wrote to John Russell, Lord Chancellor of England and Bishop of Lincoln concerning a plot that had been uncovered in London:

‘Certaine personnes of such as of late had taken it upon thaym the fact of an enterprise as we doube nat ye have herd be attached and in ward we desir’ and wol you that ye doo make our letters of commission to such personnes as by you and our counsaille shalby advised forto sitte upon thaym and to procede to the due execucion of our laws in that behalve. Faille ye nat hereof as our perfect trust is in you….’

Moving on to August 1485 it’s unclear whether Francis was present at Bosworth Field as Richard had sent him to guard the south coast against Henry Tudor’s threatened invasion. Attainted of high treason after Bosworth in 1486 Francis’ lands were granted to Jasper Tudor, Duke of Bedford, uncle to Henry, who was of course now Henry VII. Jasper would hold them until his death in 1495 after which they reverted back to the Crown. Whether he was at Bosworth or not, June 1487 found Francis definitely at the Battle of Stoke, where, as the story goes, he was last seen making his escape swimming across the River Trent on horseback (3). Confusingly there is a rather vague story attached to some accounts of Francis’ disappearance regarding a letter of safe conduct issued to him and four others on the 17th June by James IV of Scotland permitting them to enter Scotland and stay for a year. Whether Francis took this offer up or not no evidence has survived of his presence in Scotland at that time other than a rather woolly story told by a ‘simple and pure/poor person’ from York to the Mayor of that city in 1491 stating that he/she had seen him there (4). However, to backtrack a little, in 1466 Francis had married the Earl of Warwick’s niece, Anne Fitzhugh, the daughter of Henry, Lord Fitzhugh, and Alice, daughter of Richard Neville, earl of Salisbury. It was Anne and her mother, who made strenuous and brave efforts to try to find Francis sending Sir Edward Franke, northwards in search of him. Clearly neither Anne nor Alice, the sister of the great Richard Neville the Kingmaker, were pushovers. Alice wrote to Sir John Paston

‘Also my doghtyr Lovell makith great sute and labour for my sone hir husbande. Sir Edward Franke hath bene in the North to inquire for hym; he is comyn agayne and cane nogth understonde wher he is. Wherfore her benevolers willith hir to continue hir sute and labour; and so I can not departe nor leve hir as ye know well; and if I might be there, I wold be full glad, as knowith our Lorde God, Whoo have you in His blissid kepynge (5).

These attempts as far as we know were sadly futile. Francis had disappeared into the mists of time.

This leads to the 18th century tale that during the process of a ‘new laying‘ of a chimney, a secret underground room was discovered at Minster Lovell, wherein a skeleton assumed to be that of Francis was found. Some accounts have the corpse still whole and richly clothed. Either way the remains, so the story goes, were found ‘sitting at a table, which was before him, with a book, paper, pen etc etc; in another part of the room lay a cap, all much mouldered and decayed. Which the family and others judged to be this Lord Lovell, whose exit hath hitherto been so uncertain’ (6). It is said the skeleton conveniently disappeared into a puff of dust upon the room being opened – which is highly unlikely. The underground room or cellar has never been found according to the English Heritage Guide Book written by A J Taylor but why let facts stand in the way of a good story. The conversation which followed, if it ever happened, which I doubt, can well be imagined ‘What happened to the body dolt?’ – ‘It disappeared into a cloud of dust sir‘. It certainly would seem a strange place for Francis to head to as a hunted fugitive because as noted above it was now in the ownership of Jasper Tudor although to be fair he may not have lived at the Hall much. Hopefully this old chestnut has now been well and truly put to bed.

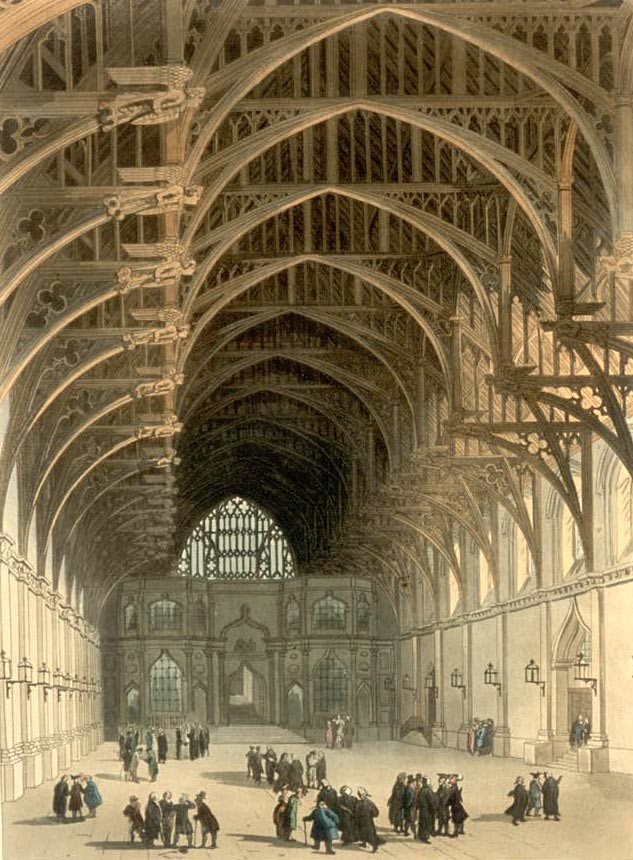

To return to the house itself. It was built around a quadrangle with the southern side facing the River Windrush. It’s hard to imagine a more idyllic site. Approached from the north an impressive diaper patterned cobbled path leads up to the entrance porch which leads into the hall. The solar and private apartments are grouped to the west, the kitchen and service quarters to the east. There was a chapel to the north of the hall above the entrance porch. Nothing remains of the chapel today, the four windows of which can be seen in Buck’s engraving.

The diaper patterned cobbled path leading up to the Porch

Vaulting on the ceiling of the porch

Interior of the Hall. Photo thanks to Martin Beek

In 1602 the Hall was sold to the Coke family who owned it until 1812. It was during the ownership of the Cokes that the Hall was dismantled about 1747. The remains were then left to fall into decay although part of them were used as farm buildings (7). It then passed through several owners until finally in 1935, the then owner, a Mrs Agnetha Terrierre passed the ownership into the hands of the state.

THE SOLAR

The solar was accessed by a staircase south of the dais in the Hall. Lit by two large transomed windows, both with tracery, it had a fireplace, traces of which can still be seen, and set of stairs leading up to the chapel. The solar would have been the personal and private chamber for the family. Perhaps it was in this room that Francis spent time with his friend, now King Richard III, when Richard, and possibly Queen Anne Neville, Warwick the Kingmaker’s daughter, stayed at the Minster Lovell in 1483 during his Progress after his Coronation.

North West Building

This once two storied building, which probably contained further private apartments of the Lord and his family initially survived the destruction of the 17th century and was being used in the mid 19th century as a barn – a door being cut into one of the walls to enable carts to be driven in. This unsurprisingly led to the roof collapsing. Then a small cottage was built in that area, the foundations of which have now been removed. All that remains of this cottage is a small fireplace built into the north wall and a window that was partially blocked up. The upper floor had transomed windows with window seats on the west side.

WEST WING

There were five room in this wing which led to the South West Tower.

South West Tower

The tower consisted of 4 floors, the top floor having battlements. Its slightly later than the rest of the buildings being later 15th Century. On the ground floor were garderobes, the pit being on the side nearest the river. A external staircase led to the first floor and access to the remaining floors.

On the East Side of the courtyard were situated the kitchens, bakehouse and stables.

ST KENELMS CHURCH

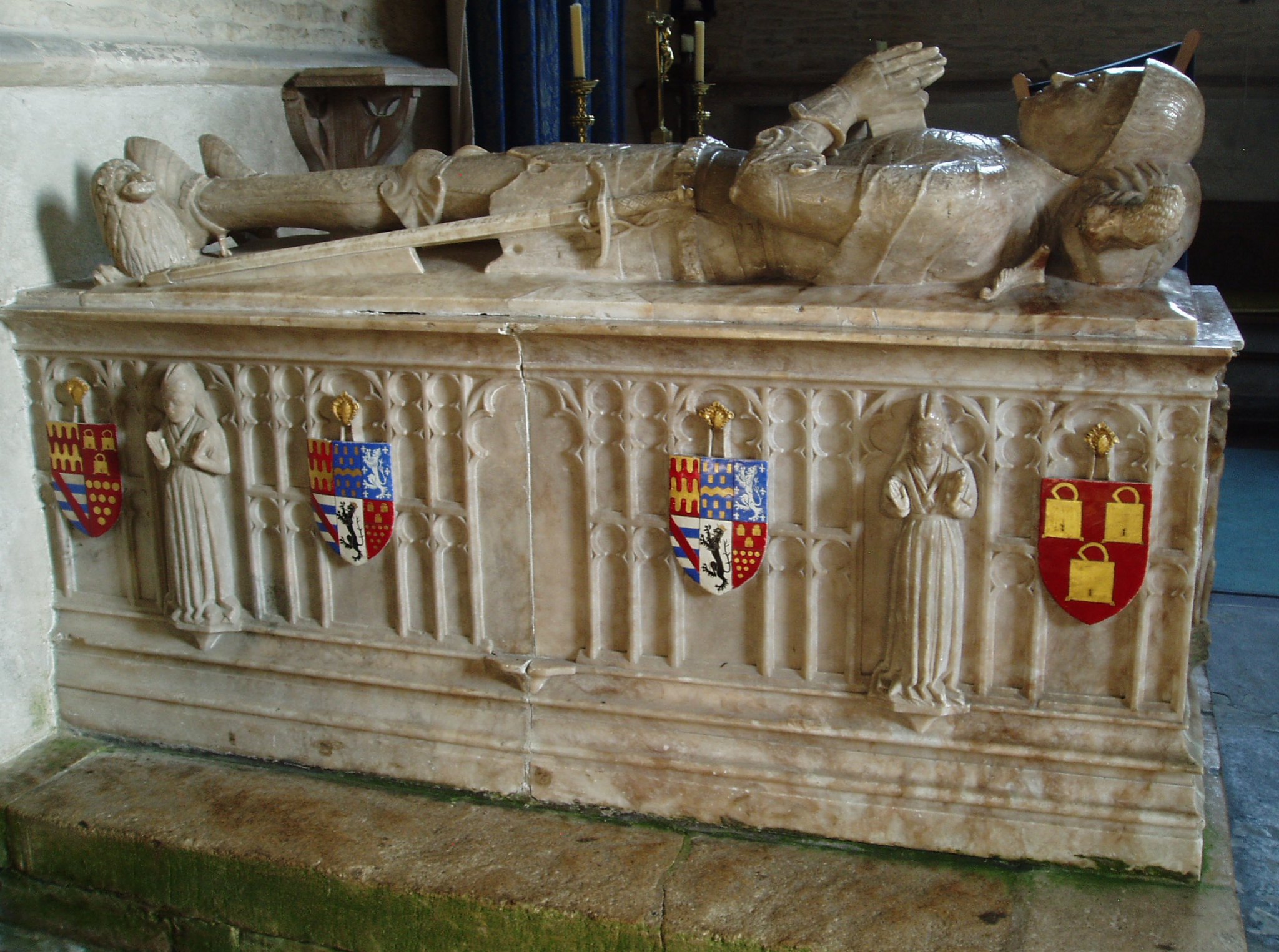

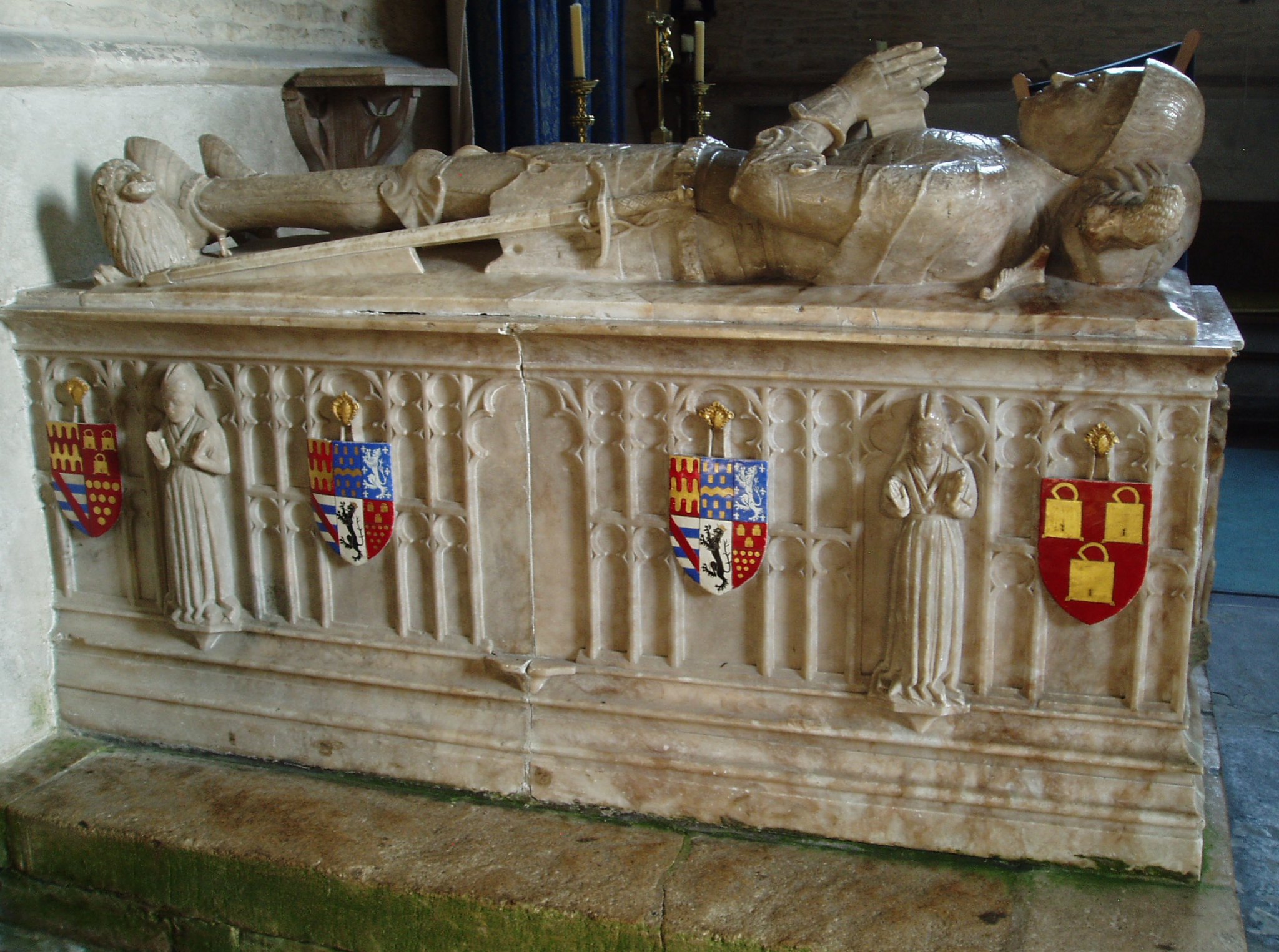

‘Lovell’ tomb in St Kenelm’s church. Photo thanks to Aidan McRae Thomson

We cannot depart the Hall without a look around St Kenelm’s Church which stands close by. Most of the church that can been seen today is 15th century built on earlier foundations. In the transept can be found a fine alabaster tomb chest with the effigy of a knight. The effigy’s armour and the costumes of the weepers dates it to the mid 15th century. Traditionally a member of the Lovell family it could be either William Lovell (1397-1455) or more probably his son John (d.1465) (8). Unfortunately due to the lack of an inscription it cannot be said with certainty whose monument it is.

St Kenelms Church seen beyond the ruins of the North West building. Photo @Canis Manor

Entry into this wonderful place, now in the care of English Heritage, is free of charge. If you should ever fancy a wander around these evocative ruins I would suggest you wrap up and go in the quieter months. The summer months can be rather busy with families picnicking and children splashing in the River Windrush. And who can blame them – there are not many places that can match Minster Lovell for being quite so magical.

For an interesting article on the tomb click here

1) BHO Minster Lovell: Manors and other estates pp184-192

2) Richard wrote a letter to his mother 3 June 1484 requesting ‘my lord Chamberlaine..be your officer in Wiltshire in such as Colynborne had’ Richard III Crown and People p105 Kenneth Hillier

3) According to Francis Bacon ‘there went a report that he fled and swum over the Trent on horseback but could not recover the other side and so was drowned. But another report leaves him not there but that he lived long in a cave or vault’.

4) Lovell, Francis, Viscount Lovell Rosemary Horrox Oxford DNB and Last Champion of York. Francis Lovell Richard III’s Truest Friend p.8. Stephen David. Neither Horrox or David have given the primary sources for this story.

5) Stoke Field p.86. David Baldwin. Source The Paston Letters A.D. 1422-1509. Ed.James Gardiner (1904).

6) Letter written by William Cowper, clerk of the Parliament to Francis Peck, an antiquarian 1737.

7) Minster Lovell Hall p3 A J Taylor

8) Memorials of the Wars of the Roses p151 W E Hampton

If you liked this post you might also like:

JOHN DE LA POLE EARL OF LINCOLN AND ELSTON CHAPEL – A POSSIBLE BURIAL PLACE?

SIR THOMAS BURGH c.1430-1496 AND GAINSBOROUGH OLD HALL

STAINDROP CHURCH – A NEVILLE MAUSOLEUM

Ashby de la Zouch Castle – Home to William Lord Hastings

SIR WILLIAM STANLEY – TURNCOAT OR LOYALIST?

CROSBY PLACE HOME TO THE DUKE AND DUCHESS OF GLOUCESTER 1483

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()